GALERÍA MARITA SEGOVIA: FIELDS OF COLOUR, GEOMETRY AND ABSTRACTION

Feb 8, 2020

art madrid

The gallery from Madrid Marita Segovia will exhibit in Art Madrid, a selection of the art work by four artists with different identities and artistic discourses but with clear aesthetic, formal and symbolic connections. Abstraction and geometry define the work of these four contemporary creators: Anke Blaue, Eduardo Martín del Pozo, Lourdes García O'Neill and Manolo Ballesteros.

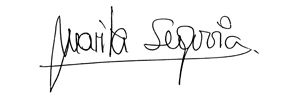

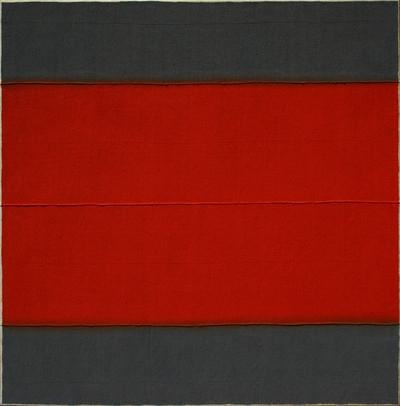

The colour field paintings is one of the many movements of the American abstract expressionism, its greatest exponent being Mark Rothko. The compositions in the "colour field paintings" are characterized by large flat surfaces combined with colour which different shades of light are played with. The artist Anke Blaue (Germany, 1967), goes beyond the chromatic game and creates, without impediment, a spontaneous communication through the visual effect produced by the inherent characteristic of the material used.

The blues, greens, reds and yellows chosen by Blaue become more solemn as they are embodied on pieces of antique linen, patiently superimposed one on the other, creating compositional lines of extreme subtlety that, together with the granulate characteristic of the fabric, produce a special agitation and sensation of abyss.

The colour planes are also a constant in the art work of Manolo Ballesteros (Barcelona, 1965), who usually combines a maximum of two colours in his works. Ballesteros tries to find himself. For him "painting is a way of thinking, it never has a concrete meaning. What it does have is musicality, it tends to spirituality because of the rhythm, the spaces and the tones of colour".

In his gouaches on paper he creates geometric shapes that subtly take over the canvas, creating capricious forms. During the last few years his art work has experimented in the domain of abstraction, playing with geometric complexity through the uniformity of pigments and the reduction of profiles. As a result of these investigations his most recent work reflects the convergence of rounded shapes on monochromatic backgrounds where the viewer is trapped in an energetic and dynamic art.

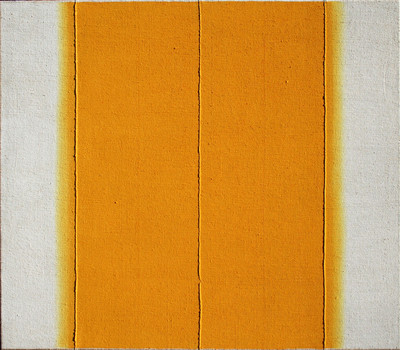

In the compositions of Lourdes García O'Neil, we see again reminiscences of some artistic tendencies belonging to the American expressionist movement. The artist from Seville, combines in her large format canvases, abstract forms of different colours. Through colour and form, and letting herself be carried away by feeling, in her most recent work she achieves a synthesis that discards any insubstantial element previously contained in it.

In some of García O'Neil's works, the forms are diluted in the plane, moving us to the "blocks of colour" of the American artist Helen Frankenthaler. Without falling into their geometry, her production can suggest Equipo 57 because of the loose and fragmented line.

Eduardo Martín del Pozo (Madrid, 1974) is perhaps the most figurative of the four artists. In some of his works, we find simulated spaces, while in others, such as "2017.53", these spaces fade away and become weightless and imprecise. "2018.24" shows us how Martín del Pozo accentuates the indetermination of the configuration of his work, accentuating the purity and definition of his gesture, which causes it to originate a framework hanging on the surface of the support.

Martín del Pozo's research is based on the relationships that can be established between the plastic arts and other manifestations, specifically music. The artist plays with rhythm, repetition and symmetry as if his works were musical structures.