HAPPY 2018 WORLD BOOK DAY!

Apr 22, 2018

Breaking News

Fortunately, speaking today of the World Book Day is something familiar. It is a consolidated celebration that we all look forward to. Spring and good weather come, and walks in the park and reading a book are one of the greatest pleasures in life.

April 23rd is a designated date. We celebrate the anniversary of the death of Cervantes, along with the birth of Shakespeare, in 1616, as well as other important milestones for universal literature. For this reason, UNESCO decided in 1995 to dedicate a day to this celebration, and since 1996 it is celebrated worldwide, although the organisation of fairs and meetings around the book are much earlier. In fact, in Spain the first book fair is recorded in 1926 during the reign of Alfonso XIII.

There are many activities ongoing on these dates. We can highlight the exhibition "Pasa pagina. An invitation to read", in the National Library Museum. It is a proposal in which visitors are invited to reflect on the role of reading and the impact on people's personal lives. What does reading mean? A tour completed with audio and visual elements, photographs and books gathered under the maxim "the more you read, the more you live". A great truth.

Paradoxically, the Madrid Book Fair (the 77th edition) is held within a month in the Retiro park, this year with Romania as the guest country. This meeting is the ideal occasion to combine different artistic disciplines where boundaries are blurred and confused, starting with the poster of the fair, made this year by the illustrator Paula Bonet, or booths dedicated to the artist book or publishers focused on mixed illustration and narrative projects.

And for those who want to get started in art with a good reading, we bring you a short list of recommendations:

“Letters to Theo” (Vincent Van Gogh): compiles the letters that Van Gogh sent to his brother Theo and are a direct testimony of the personal artistic experience of this essential author.

“Salvador Dalí: the diary of a genius” (Salvador Dalí): a personal diary to know the most hidden intimacy of this genius so often described as lunatic.

"Leonardo da Vinci. The biography", by Walter Isaacson. This writer has already addressed the biography of other great masters. On this occasion, he reviews the vital story of this renaissance figure that is still up-to-date.

"Joan Miro. The child who spoke with trees", by Josep Massot. The writer has made a profound investigation into the life of this iconic artist of the 20th century around which there is still a great ignorance.

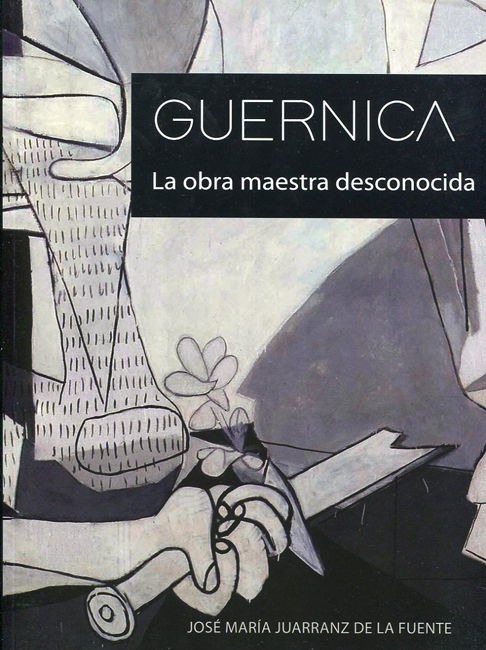

"Guernica. The unknown masterpiece", by José María Juarranz. This book is the result of several years of research that deals with the historical, political, social and personal context that motivated the realization of this masterpiece of the 20th century.