Exhibition\"Myths of pop\" in Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

Jun 11, 2014

art madrid

| The last time we enjoyed POP in Madrid was in 1992 with the great Pop Art exhibition at the Reina Sofia Museum. Now, over 20 years later, the curator Paloma Alarcó, Head of Conservation of Modern Painting from the Thyssen, proposes a rereading of the movement that erased the barrier between high and low culture, Pop, from the experience and the evolution of art we have aquired with the XXI century. |

|

|

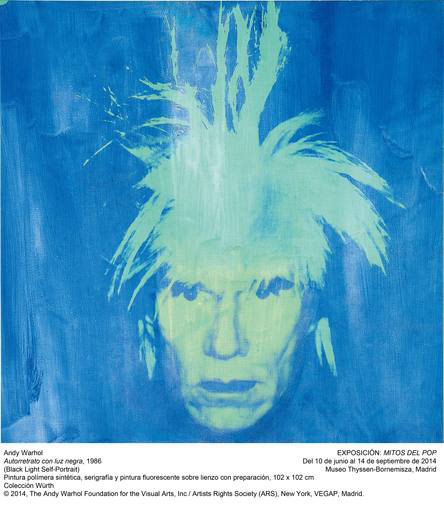

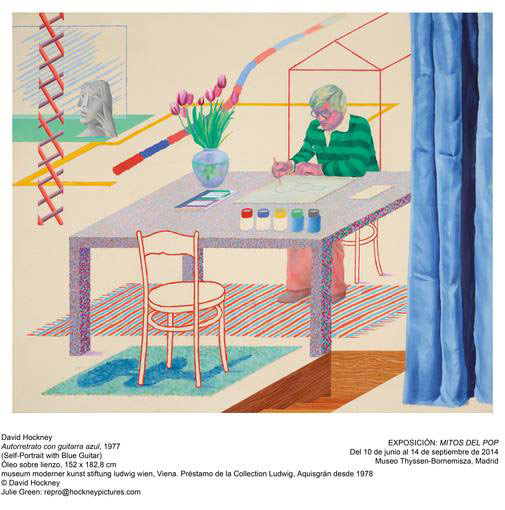

Myths of Pop, in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, shows more than 100 works, the most representative and repetaed images of those pop myths, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Tom Wesselmann, Roy Lichtenstein, David Hockney, Richard Hamilton, Robert Indiana and the Spanish pop representación of Equipo Crónica and Eduardo Arroyo.

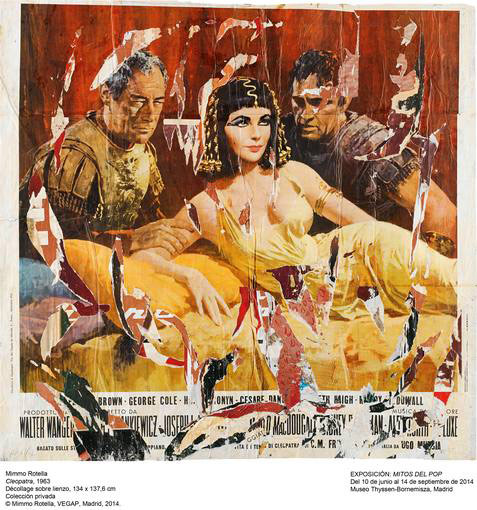

Paloma Alarcó' s selection includes pioneers of British pop, classic American pop and its expansion in Europe tracking the common sources of international pop to review and revisit the myths that have traditionally defined the movement. The goal, according to organziadores is "to show that the mythical images of these artists hide an ironic novel code and perception of reality, a code that is still alive in the art of our time." The exhibition is not ordered temporarily, but rather focus: begins with the collage, advertising and comic, with great works of Hamilton, and continues with rooms devoted to major pop icons that we all know as the Beatles, Warhol's Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra, until the still lifes, urban erotica, history painting and art about art.

|

|

| The exhibition features works from over fifty museums and private collections around the world, with outstanding loans from the National Gallery in Washington, the Tate in London, the IVAM in Valencia or the Mughrabi collection of New York. A comprehensive example of the big names who invented an art from their everyday objects, consumer products, television, cinema, advertising and comic with an aesthetic and an attitude that got to reconnect the average citizen with the Great Art. Pop, beyond slogans and color, proposed a reading of world history and politics full of irony and humor. |

|

|

As the Curator notes in the text that presents the exhibition "pop hides a fascinating paradox. On the one hand it was an innovative movement that paved the way for postmodernism, yet expressed a clear orientation towards the past. Pop´s ambition focused on connect with tradition using new media derived from television, advertising and comics was concentrated mainly in the reassessment of styles and artistic genres and reinterpreting the works of the old masters, making tributes or irreverent parodies with them". |

|

| Myths of Pop includes a program with pop cinema, concerts, conferences and even the development of a comic book published for the occasion. The new exhibition at the Thyssen can be enjoyed until 14 September. |