El Greco and the modern painting exhibition in El Prado Museum

Sep 10, 2014

art madrid

|

|

La visión de san Juan, El Greco. This year marks throughout Spain the fourth centenary of the death of the Greco, Cretan painter who came to Toledo in 1577 and settled there making the city the cradle in which he developed his most successful work and the time of maximum splendor. El Greco was a reference not only in his time but its influence persisted over time, as a mirror in which the main representatives avant garde of 20th century looked themselves. In the exhibition "El Greco and the Modern Painting" in the Prado Museum until 5 October, we can track the mark left by the painter in the work of Manet, Cezanne, Picasso, Delaunay, Modigliani and the Czech avant-garde. |

|

|

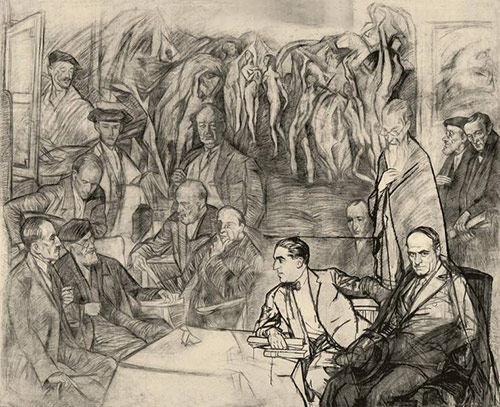

Composición (La Oración en el huerto), Adriaan Korteweg. El Greco's work was rediscovered in the early twentieth century with the first exhibition in the Museo del Prado (1902) and the formation of new collections associated with his paintings of modern artists. In Central Europe, the Greco inspired the expressionism of Beckmann, Kokoschka or Korteweg and the modern Parisians that played with surrealism. |

|

|

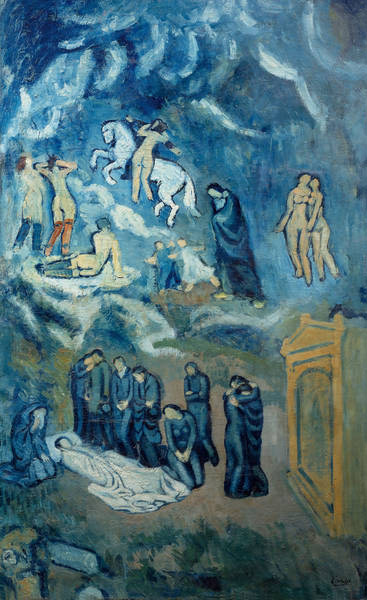

Evocación. El entierro de Casagemas, Pablo Picasso.

But if there is an outstanding painter clearly influenced by El Greco was Pablo Picasso, whose early drawings and paintings from 1898 show their penchant for the artist from Toledo. This became very intense in his blue period (1901-1904) in which he reelaborated the work Evocation in an original way. |

|

|

Mis amigos, Ignacio Zuloaga. The assessment of Greco in Spain was very noticeable from the 1890s and reached its peak in the figure of Ignacio Zuloaga who collected many of his works (The Vision of St. John, for example, present in the exhibition ) and then he painted Greco's details on his own pictures as a tribute. After II World War, painters turned to the expressive, emotional and gesture, and lyricism of the figures of the Greco inspired the painters of the time. |

|

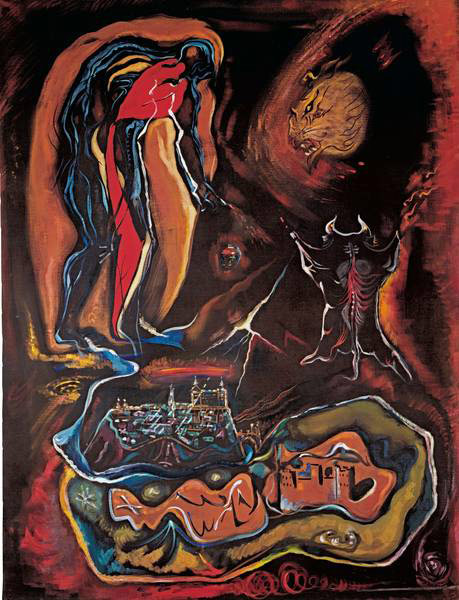

| Vista emblemática de Toledo, André Masson. |