\"ALL PROCEEDS OF THE WITHOUT REASON\" ANTHOLOGY OF CARMEN CALVO

Dec 1, 2016

exhibitions

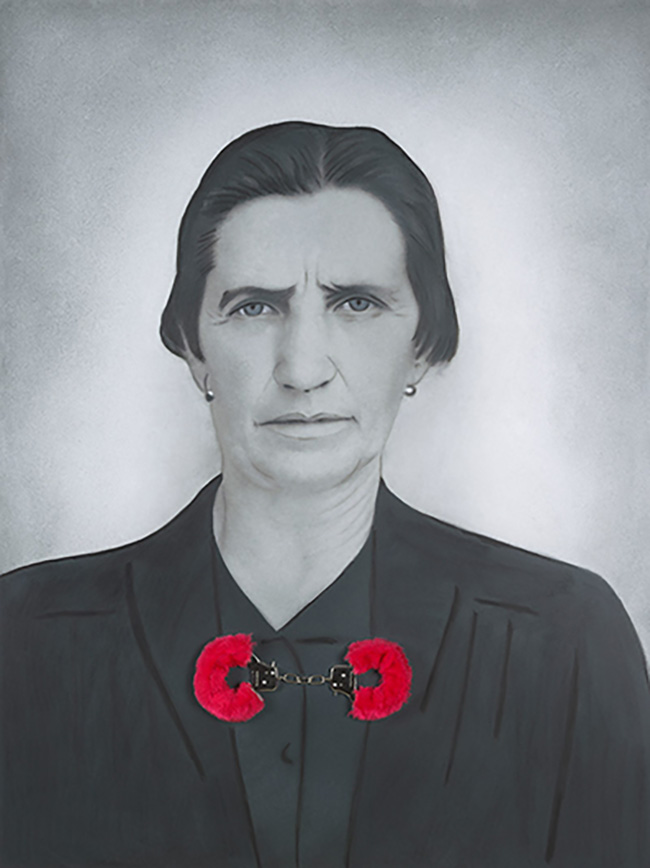

Grave charming passion, 2014 Mixed technique: collage and photography 120 x 90 cm. Collection of the artist © Carmen Calvo, VEGAP Madrid 2016

Carmen Calvo (Valencia, 1950) is a Spanish conceptual artist. Formed at the Fine Arts University of Valencia, she has won such prestigious prizes as the National Fine Arts Award in 2013. Carmen's work reflects her life; her three geographical points have been Madrid, Paris and Valencia. These three cities are present at the different stages of her dossier. To exhibit in the 1980s in the art exhibition "New images from Spain" at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, was her springboard. Since that time his career took off until today, and this places him in the international artistic scene.

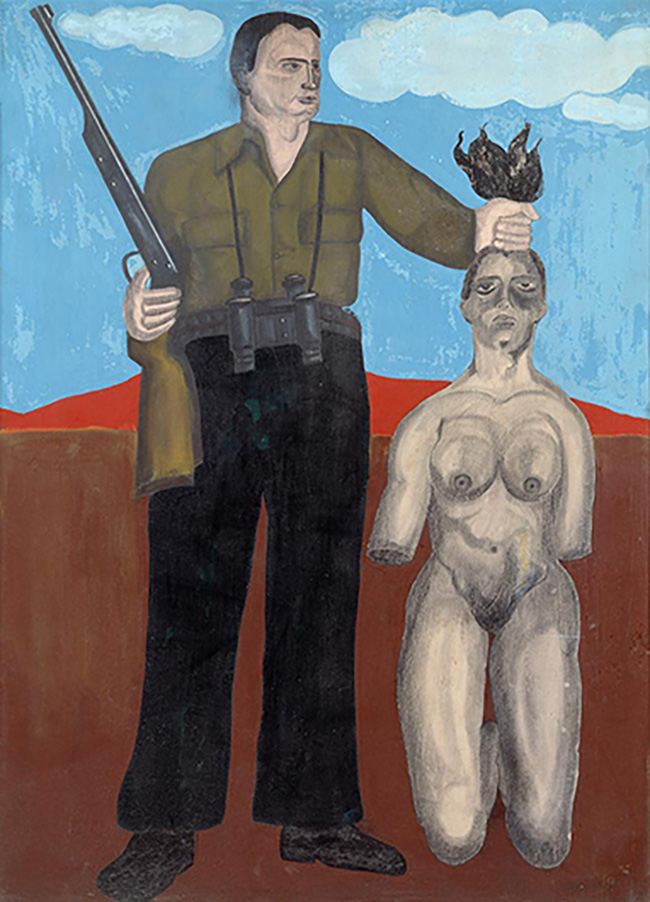

S / T, 1969. Mythical technique: gouache on wooden board 90 x 65 cm. Collection of the artist © Carmen Calvo, VEGAP Madrid 2016

The exhibition recreates a compilation of 77 works from an anthological perspective. The eclectic layout of the room, curated by Alfonso de la Torre, encompasses different disciplines such as painting, sculpture, drawing and installations. The most characteristic of this sample is its chronological and structured organization. Divided into 5 parts, these sections help the viewer to draw a global image of the artistic feeling and to know the artist herself.

The first part, "An archeology of the imaginary", refers to his stay in Paris. We talk about the 80's and the way to represent it is with paintings and elements of sewn clay. This part reminds us of the passion for the archeology of the artist and her relationship with the world of ceramics, since one of her first works was created in her factory.

Untitled, 1996-1997. Mixed technique on blackboard. Set of 21 pieces of 100 x 130 cm each. National Museum Collection Reina Sofía Art Center © Carmen Calvo, VEGAP Madrid 2016

The second section, "Ceremony and object", makes a jump forward in time of 10 years. Based on the 90´s, it makes a ceremonial turn towards the relationship between the artist and the object. A clear vestige of how they influence when creating her work and the meaning that she gives them. The third section, "Cannibalism of the images" is directly related to photography, one of the main characteristics of his work. The manipulation of the photos holds no secrets for Carmen, and is one of her trademarks. Since the mid 80´s it is one of the most recurring techniques, to enlarge and alter its original features, a delight for the senses.

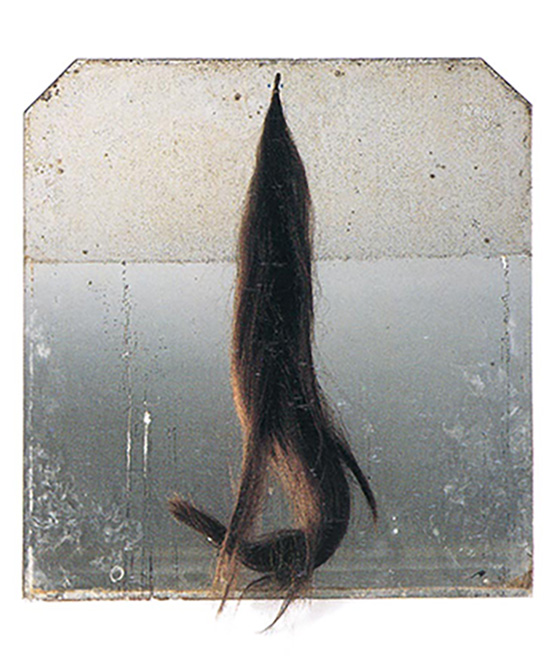

Silence II. I promise you hell, 1995. Collection National Museum Reina Sofía Art Center © Carmen Calvo, VEGAP Madrid 2016

The fourth section, "The hallucinations are innumerable", dedicates his speech to the work on paper, collage and drawing. And in the last chapter but not least, it winks at the multimedia content. This field, well loved by the artist, reveals his love of cinema and music. Two artistic modalities that have always accompanied her. With this last data we can give meaning to all his work. For this reason she has created the work "Et pourlèche la face ronde”. This is the best farewell, for an exhibition full of looks within itself and to spread the delight of the arts.