ALL WHITES OF PAPER

Jul 24, 2019

exhibitions

“Connections” is a project launched thanks to the collaboration of the ABC Museum and the Banco Santander Foundation in which an artist is invited to develop a collection of pieces that open a dialogue between a selected work of the Banco collection Santander and others taken from the ABC Museum funds. This initiative tries to promote the diffusion and artistic production around contemporary drawing, so the invited authors work almost exclusively on this discipline.

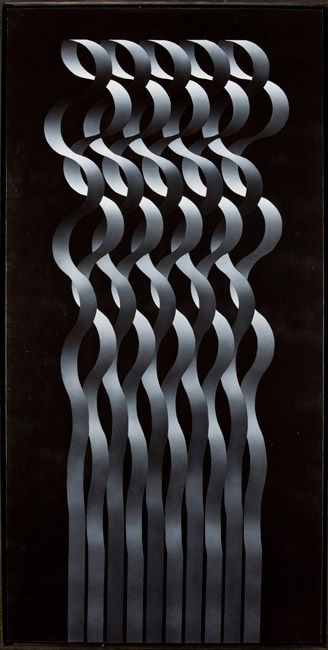

For this 17th edition of the program, the curator Óscar Alonso Molina has invited Guillermo Peñalver. This illustrator and paper lover has been inspired by the work “Modulation number 66” (1976) by the Argentinian artist Julio Le Parc, from the Banco Santander collection, and from the ABC Museum he has chosen three illustrations: “Brígida y su Boda ”(1929), by Emilio Ferrer; “The boy and the showcase” (1924), by Ángel Díaz Huertas; and "The Manly Man" (1932), by Antonio Barbero. Around these selected pieces, Peñalver has developed a project that takes as a starting point his day to day in a precarious context in which the most common and homely actions mix with the time and space dedicated to the creation of his work.

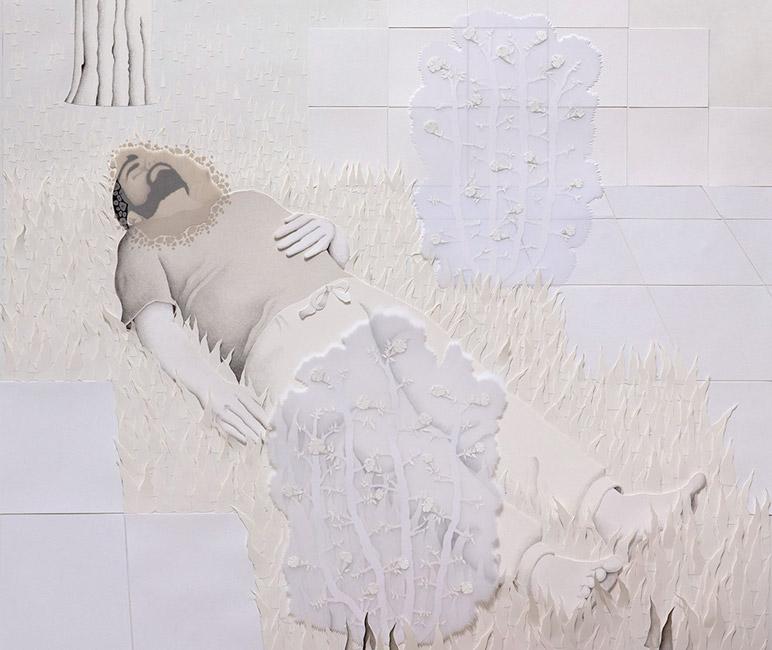

Under the title "Autorretrato en interior", the artist recreates scenes of his daily life in pieces of large format that merge the technique of collage with the pencil drawing. Overlapping cut-offs of different papers, he plays with the many shades of white, from ivory to pearl. The images take us to a known environment, to everyday situations in which we can recognise ourselves and find our own personal history.

Peñalver wants to convey with this collection the presence that the creative spirit has in his daily life and the lack of resources that artists sometimes face. The scenes show a shared space, where the resting area and the workplace blend in, making it clear that it is not always possible to own a private studio to create; but, at the same time, it is remarkable the naturalness with which the artistic desire is part of the author's life hardly without transition between the different activities of his daily work.

The author shares with the viewer the intimacies of this creative process, where the smallest detail can trigger a desire to cut, fold and draw. The set of pieces condenses that uncontrollable impulse to create, which permeates each of the elements of its reality. The result is an intimate and honest work, where situations and thoughts materialise in clean and delicate pieces that need attention, not only to notice the depth of the white colour, always used intentionally, but to discover all the details, the invisible work, the care put into these everyday scenes. Peñalver subtly opens his inner world for us to find him as a spy looking through a window, and faces the naturalness of the home and things done without artifice or imposture.

ABC Museum. "Autorretrato en interior" by Guillermo Peñalver. Until 15th September.