AN INTERVIEW WITH ISABELITA VALDECASAS

May 23, 2019

exhibitions

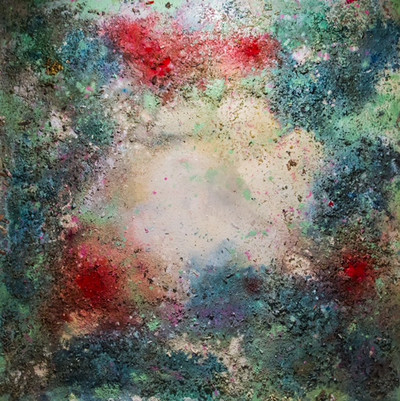

Although Isabel began her pictorial trajectory in the world of figurative art, later she began to explore the expressive power of abstraction, with strong plasticity and the use of real materials extracted from the places she was visiting. Her latest series, "Cosmogonías", is an abstract expression of a moment of Genesis, a metaphor of the origin of life that coincides with a moment of change in her career. Today we interview this Sevillian painter and we approach her to know her work in a more personal way.

You studied Art History and soon after you moved to London where you worked at Christie's, could you describe how your experience was there and what are the differences between the British and Spanish markets?

After I studied Art History in Seville, I managed to go to London to continue studying. My hunger to see the museums, the wonderful works of art and everything that was going on was insatiable. I learned a lot not only about art but also about the world that surrounds it: exhibitions, galleries, auctions, market, etc. I realised that in Spain we were very far from the artistic dynamism that was breathed there. There were weekly auctions of a whole artistic period, for example, the week of the Impressionists was terrific, you could see Monet’s, Manet’s, Renoir’s, Van Gogh’s, etc. all together on sale. The same happened with the old painting, the furniture, the jewels... Britains have always had a long tradition of buying and selling works of art of great value; in that, Spaniards go behind.

As a result of your experience in London, you started painting. How did you take that step and in what style would you currently place your work?

I already painted a lot before moving to London, although it is true that I did not dedicate myself professionally to it; that came after my return. I needed to work since I did not know where to start living from this. In Madrid, I worked at Christie's for a few years while I was drawing in my spare time and painting furniture by order. The step was not sudden, little by little, I painted more and more, each time I filled more, and each time I needed more to feel good. One day I was offered to make a mural. I had never painted such a large surface before. I jumped without hesitation (with a very short time, what a foolish kamikaze!) And I understood that I would never be completely satisfied with myself if I did not dedicate myself to what I really liked and I was good at. So I began to make murals, I remember it as an exciting, difficult, learning and monumental-back-pain period. Then came the crisis and with it a huge personal crisis... that's when I went from the figurative art to the abstract art, and the Cosmogonies were born. So I cannot define my style, right now I'm doing abstract and very material works, but I start from the classic and figurative, and, in the end, I always go back to basics.

In some press statements, you have made it clear that both music and travel are two key elements when painting. Could you explain what your creative process is like and how does the travel and music influence that process?

The creative process is slow; it is not only the moment of execution of the work. In this, trips play an important role, although I could not define precisely which one. I am fascinated by the nature and sensuality of the landscape, and by sensuality, I mean the senses: smell, light, colour, the sound of the wind, the touch of sand or moss, the local product of the land that one eats during a journey. Everything is related to the land that is visited. The painting that comes out after a trip to Germany or Sweden with those greens and grays, those clouds and skies, the smell of cold or grass in summer, the sensation of stillness... has nothing to do with a painting you make after a trip to Cartagena de Indias where everything is colour, noise, humidity and Caribbean joy. I take many elements for my work every time I travel, and sometimes I think they will stop me at a customs office for the amount of local "souvenirs" I bring.

The music is also inspired by the places where it is made. I paint because I do not make music and I'm almost not able to get out of bed without it (I do not know who once told me that I exaggerate, like a good Andalusian). I do everything with music; it's like an engine; it gives me joy and accompanies me in my long hours at the studio. I listen to everything, well, not everything... but almost. It is my great, great hobby.

What does art bring to your life?

Art brings a thousand things to my life. On the one hand, it is my job, so it gives me responsibility, challenge and gratification. Art is my concern and, at the same time, it is what comes naturally to me. The art of others, whether plastic or not (literature, music, movies...) is my passion, my intellectual food. But I like more when shared, commented, analysed and discussed with more people; from there, interesting reflections, ideas and sometimes big laughs always come. It is fundamental to laugh seriously.

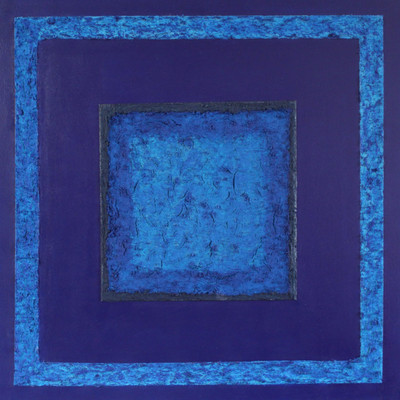

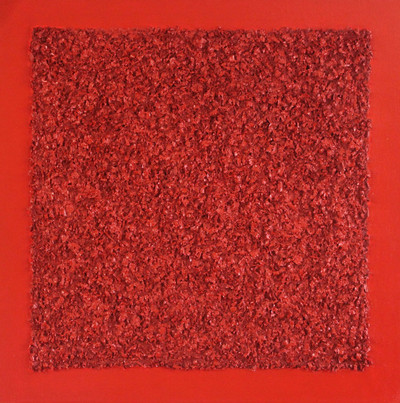

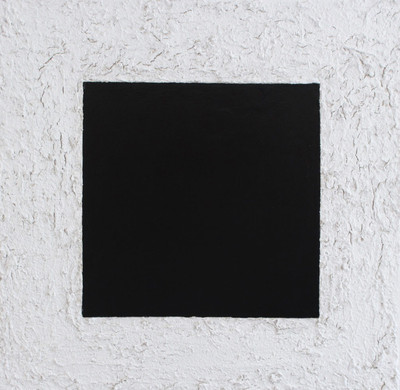

Natural elements such as sand, moss or rocks are components that can be found in your work. What is the intention of using these materials in your pieces?

The natural elements that I use are both a compositional part of the work and a symbolic part. All this was emerging little by little and unconsciously. On the one hand, they add texture and volume to the work, create reliefs and material bodies; but they are also there with a purpose, they reflect that everything is part of nature, no matter how processed or intervened it is in the hands of man, it comes from the earth and end in it by good or bad, resurfacing, though in the process we end up extinguished by brutes, beasts and self-destructive. I am obsessed with recycling and with the ambiguity or duality of this language, since we are part of that nature that we are destroying, it is us who are going to destroy ourselves since we are a symbiosis, an "everything" in a fragile equilibrium.

Could you talk about the underlying meaning of “Cosmogonías” and how it arose?

“Cosmogonías” emerged little by little and almost by chance as a small Big Bang. Then, they shaped and consolidated in my head and the canvases. On the one hand, there is the idea of the immensity of nature in the face of our insignificance, both towards the boundless infinite and towards the infinitesimal and microscopic. They coincided in time with a change in my life when I started doing abstract works, so they were like a genesis. I needed to give them a name, and that is where the word Cosmogenesis, the origin, comes from. So they can also be interpreted as a new beginning, the gestation of something. They are works inspired by the source of life, the fascination and mystery of creation from the tiniest cell in a microscope and its chemical reactions to the infinite of the cosmos, so similar among them. They are also introspection and a call for attention to the basics, the classic, the natural and the organic in this digitalised, denatured and plastic world.

How does an artist of the 21st century keep a little apart from the new digital habits and the imperative of social networks?

New digital habits do not interest me much. I think they are necessary and useful, of course, but they do not particularly attract me. I need contact with the material, with the tangible. There is also an aesthetic and compositional part that I believe should go beyond what is marketing and is fashionable. But there is no doubt that to survive in the 21st century we have to keep up to date with social networks and the digital age... what can I say? It is like the child coming back from school and wants to play, but knows that he must do his homework first.

Do you think that concern for the environment is more and more frequent among contemporary creators? What difficulties and innovations have you found to work accordingly to these principles?

Fortunately, there is much more awareness in this generation of caring for the environment, recycling, not polluting etc., and, in fact, this is reflected in current art. It could not be otherwise. Each era must be reflected in its contemporary art. But it is also true that this destructive madness is more aggressive than ever. There is more pollution increasing without measure and it is something that scares me and worries a lot. I will not be hypocritical, I recycle and I try to be as careful as possible, but I cannot stop thinking that it is never enough. In the end, we live in the place and time we live.

Difficulties I have found several, innovations ... I think none! One has to test the materials well to verify that they will be durable or, for example, to have faith that the pigments and other products of Fine Arts sold as "organic" or "ecological" really are so. Another difficulty has been to be doing a work inspired by the Mediterranean Sea with algae and sand collected on the beaches and suddenly I have run out of Posidonia or some other local element, then I have to resort to a charitable soul that will collect materials to send them over... I do not even want to think what the postmen face would be if they have ever opened one of those boxes full of seaweed, weeds, shavings and sand...! Once a friend came carrying 15 kg of Tarifa’s sand for some paintings.

Innovations I do not think so, everything is invented; the question is to make unique pieces with their own style. Time will tell…