WHAT DOES ART HAVE TO SAY ABOUT THE WORK DAY?

Apr 28, 2019

Breaking News

Our life is mostly marked by the time dedicated to work. Much of what we are and others see, is linked to our profession. Art is no apart to this phenomenon, and in fact, some artistic movements are to some extent indebted to the influence that technological advances in work have established in production processes and large factories. As a kind of second industrial revolution, the innovation of the production guidelines and the modernisation of the machinery, as well as the professional specialisation, have generated a work culture today almost inseparable from the idea of an advanced and up-to-date society.

The impact of these changes on production processes appears in the arts. We all know the parody of the assembly line that Charles Chaplin made in his film "Modern Times" (1936). Although the context of this film is the crisis that emerged after the Great Depression, the adverse working conditions of the personnel of the large factories reflected in the movie can be extrapolated to any other place in the world. A paradox poses between the inclusion of machinery that replaces human labour and relieves them of mechanical work, and a higher demand for workers forced to perform more and better.

But art has also echoed the positive effect of these advances for the work-life. Futurism, an artistic movement of the early s. XX that preceded Cubism and expanded worldwide, is essentially based on the capture of movement, speed, dynamism and progress. For this reason, many of the most representative pieces of this trend include machinery and technological devices associated with the evolution of society and the dizzy speed with which things happen in modern times. Futurists also developed a manifesto, released in 1909 by the Italian artist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, which reflects some of their main ideas, always around the treatment of speed and beauty of machinery as a sign of an era marked by advance and innovation.

The inclusion of references to the labour world in the Soviet propaganda posters is also paradigmatic. While Futurism was a free artistic movement initiated in Italy, for the Soviet Union, propaganda was an essential diffusion tool, which the regime knew how to use skillfully to expand its message and win supporters. The communication of a discourse based on the duty of citizens to work, on the dignification of men and women with effort, on the benefits of collective commitment and rural sacrifice, resulted in posters with numerous work scenes that today shape a style and an aesthetic unmistakable.

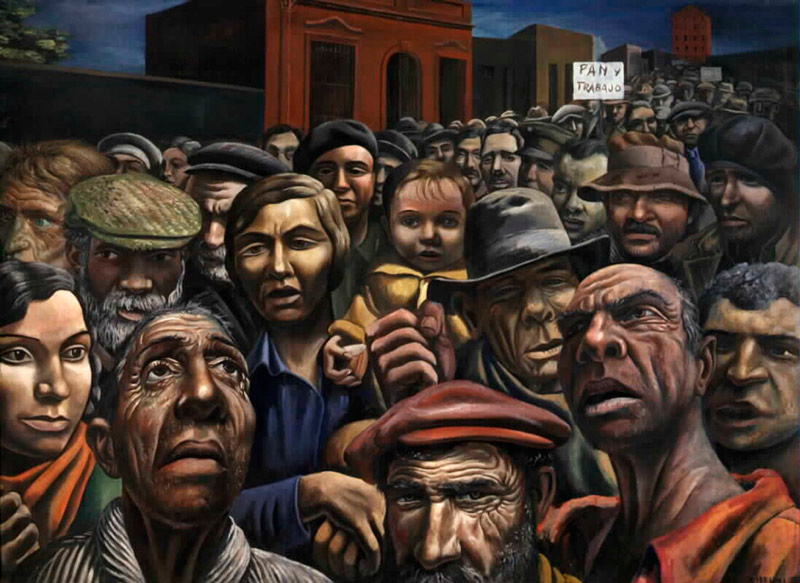

In the decade of the 30s, other artists also began to portray the hardships of work and collective demands asking for better conditions for employees. Do not forget that the date chosen to commemorate Labour Day, the 1st of May, is a tribute to the martyrs of Chicago, some anarchist trade unionists who were executed for fostering and participating in various revolts to claim an 8-hour workday, in 1886. Half a century later, the demands of the workers still originate protest movements, reflected by the artists of the moment.

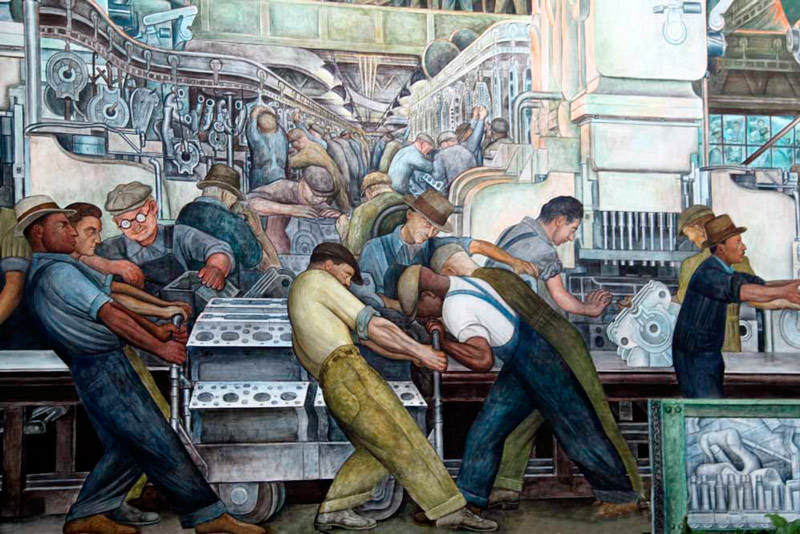

Paradoxically, it was also at this time when companies tried to spread a different image of collective effort, to dignify the role of the working class around the idea of the New Deal. This attempt to make a call to the social contribution to recover the economy, especially after the debacle of the Crack of 1929, led some companies to finance motivational murals that represented employees in the North American factories. This happened with some orders made to Diego de Rivera for Ford factories in Detroit.