ART AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: THE END OF HUMAN CREATIVITY?

Apr 13, 2023

Breaking News

The uses of artificial intelligence extend to many aspects of our reality with potential applications ranging from the design of patterns of social behaviour, the prediction of economic fluctuations or the treatment of data for the development of political measures in times of crisis. All this shows us a futuristic situation that we still see as science fiction, perhaps due to the abundance of explanations and the use of terms that our minds are not yet capable of transferring to a tangible plane. Furthermore, the union of the words "intelligence" and "artificial" to refer to these advances, in turn, generates a shadow of doubt about the value that human intervention continues to have in this context. Will we become expendable?

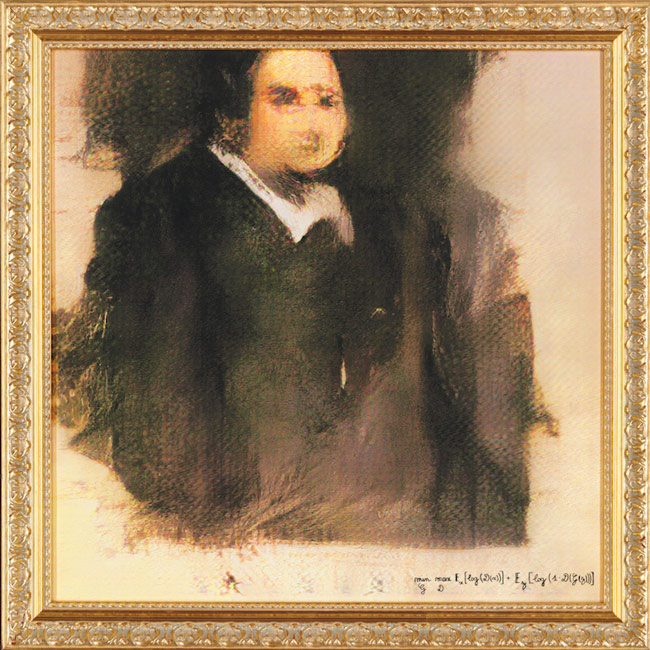

The art world is no stranger to this reality and many suggest that artificial intelligence art will be the great art movement of the 21st century. Although the resource and research on these methods began in the last decades of the last century, the matter has gained popularity since in August 2018 a work done by AI was auctioned for the first time at Christie’s (and for a price never thought of). Before long, the same thing happened with a piece by Mario Klingemann auctioned at Sotheby’s.

One of the main drawbacks that arise when dealing with artificial intelligence art is the questioning of authorship, a concept that, in art, is intimately linked to creativity, talent or genius. The fear of being replaced by a machine raises suspicions. And, probably, it is not because of acknowledging the technical achievement of programming an algorithm capable of creating a work of art, but for the insecurity caused in the spectator not being able to distinguish a work created by a human or a machine. It is a slippery terrain that affects some of the most fundamental principles of our conception of art and creativity, as we have always considered these qualities to be genuinely human and impossible to replicate.

In connection with this, other difficulties arise, such as the recognition of authorship and the intellectual property rights associated with the work. Who is the true creator? Could an algorithm see its copyright recognised? In reality, the answer to these unknowns is simple, since such rights are only applicable to human beings. The future, however, is about to be written and perhaps we will reach a dystopian (or utopian) world where machines also enjoy this recognition.

As we wait this to happen, artificial intelligence is always the result of truly human design and programming work that gives rise to the codes and algorithms that are then used, in this case, to create art. Although the term "computational creativity" exists to refer to the study of the behaviour of software whose performance and results can be considered creative, we do not doubt yet about human creativity. In fact, in the 1950s the Turing test was designed to analyse the degree of intelligence displayed by the software. According to this method, if in a set of objects, some made by computer and others made by man, could not be distinguished ones from each other, then it is that the intelligent software works correctly. The original test consisted of a set of questions that the machine had to answer, something very similar to the interrogations represented in Blade Runner to identify the replicants.

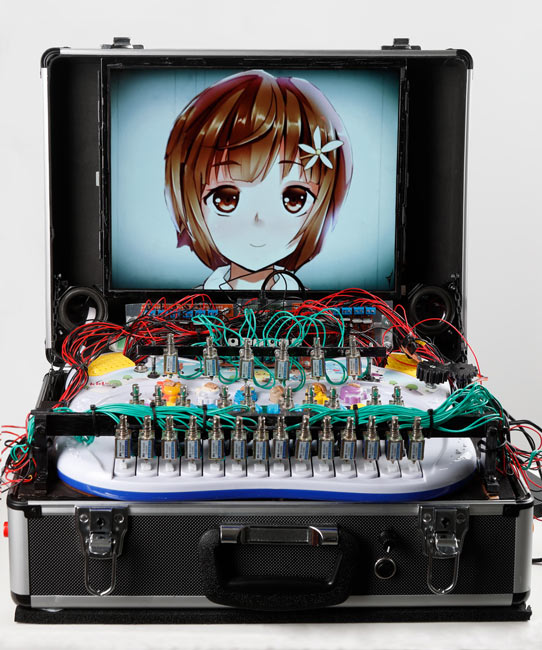

Today we undoubtedly know that the concept of intelligence is a complex notion determined by many individual factors, so giving a coherent answer to a given question would not be enough to determine if there is true intelligence. What's more, this word applied to today's programmed codes comes to identify rather the "autonomy" with which this software and algorithms work. In all this, it should be borne in mind that to generate new work, it is necessary to previously feed a database that allows the code to identify patterns and replicate them in a different creation. None of this can be done autonomously, from choosing the image bank for the database to the specific encoding system that is developed, whose syntax can guide the machine to identify movement or identify portraits. The human factor is still essential.

Despite doubts and uncertainty, we must admit that artificial intelligence opens a horizon of infinite possibilities in which many creators want to delve. It is one more window of exploration that contributes to expanding the limits of the feasible and facilitates new languages in which the intervention of the spectator is often required. For a long time, and especially since the beginning of the new millennium, art wants to get over usual spaces and overcome the traditional contemplative relationship it had with consumers. Now it is necessary the active participation of the visitor for the message to arrive. The viewer completes the discourse or affects in some way in the final result. And for this, artificial intelligence is ideal.