ART AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE: WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF CONTEMPORARY CREATION?

May 28, 2019

calendar

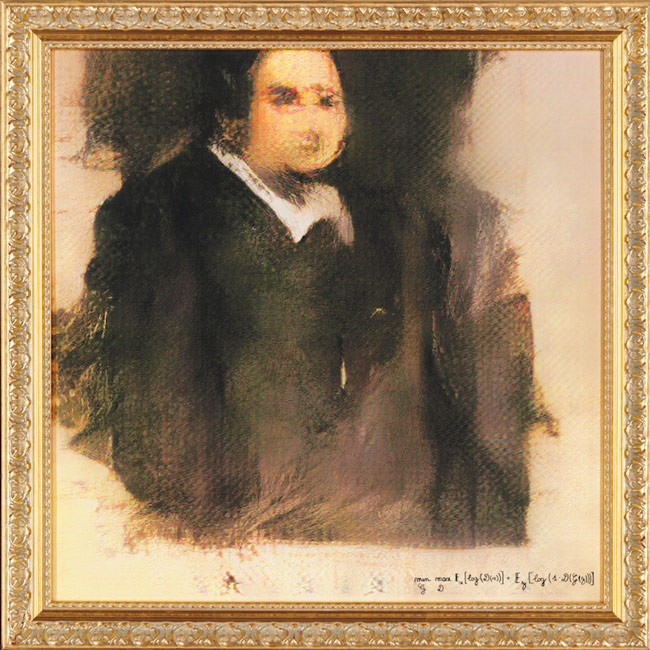

In August 2018 for the first time (and for a price never thought) Christie's auctioned a work made by artificial intelligence. Since then, the news around this technological side of art has only increased and the headlines conquer the covers of specialised media in the sector.

The main difficulty that arises in this regard, and for which many detractors of the application of technological advances to the art world maintain their criticism, is the questioning of true creativity as an exclusively human skill. While innovations and the use of technology in other sectors are welcome, to enlarge the possibilities of expansion and research, the same does not apply to the art world. Admitting that a work made by artificial intelligence can compete in the market with other pieces made by artists puts into question the very concept of art and its intellectual and aesthetic appreciation as a genuinely human skill.

However, we must approach this question with the curiosity of an intrepid researcher, willing to break moulds. Thus, the creativity gets rid off that kind of mysticism that surrounds it and is analysed as a quality that can be translated into predictive algorithms and simulation patterns with an eminently scientific approach. In this context, we begin to speak of "computational creativity" to refer to the study of software behaviour whose performance and results can be considered creative. The possibilities are almost endless, and in recent times, the development of computer creativity software has grown exponentially.

But what is creativity? Can one determine when something is creative and when not? Back in the 50s, the Turing method developed to analyse the value of the objects produced by its software was extended. According to this method, if in a set of objects, some of which were made by a computer and others by a person, people could not distinguish one object from another, then the software worked correctly. This parameter, however, cannot be applied in the same way to creativity, because people do not value here the result obtained but the value of the work based on whether it has been created genuinely by a person or by a computer.

Also keep in mind that even when we talk about computer creativity, we cannot ignore the part of human intervention in software programming. The research and applied knowledge that lead to writing that code is the result of a very personal intellectual work that also involves an in-depth analysis of the phases of the process itself. And this is where one of the main difficulties lies, because how and when does a creative idea arise? For now, it has become clear that these programs work with an initial phase of learning based on the detection of patterns, as is common in music or painting. Then, once the patterns are learned, they are applied to newly created work. But the mystery remains the same: what happens when there are no such patterns? How do ideas and creative thoughts arise in our mind? Difficult solution.

But it seems clear that artificial intelligence has come to stay and that we will have to deal with the multitude of matters that stem from this new reality: who is now the author of the work? How are intellectual property rights transmitted, if any? And many other issues.

ADA - Art Law Association and the Telefónica Foundation have organised an event on "Art and Artificial Intelligence", with the help of expert speakers, to open the debate around the challenges that new technologies pose in the art market of the 21st century. Thursday, June 5th at 7:00 p.m.