Art Dialogues

Sep 14, 2017

art madrid

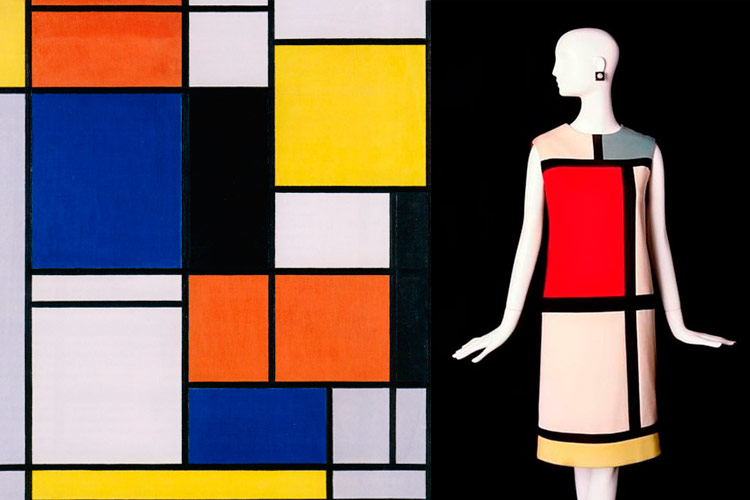

L: Piet Mondrian, “Tableau II”, 1921, oil on canvas | R: Yves Saint Laurent's design, 1965.

Art sometimes becomes a field without fences, full of paths, a mechanism of communicating vessels where inspiration flows in a multi directional manner. The homage, the emulation, the tribute, the reinterpretation move in that uncertain space between artistic disciplines to originate new pieces in which respect and admiration to what old masters had previously made are embodied.

1: Public School “La Canal”, Luanco (Spain) | 2: Mondrian Maison Hotel (France) | 3: City Hall façade in La Hague | 4: Block of buildings in Rouen (France).

Mondrian’s fame very soon went beyond the boundaries of visual arts. His simple and linear designs, which the artist only achieved after many years of work in which he developed an evolved style tending to simplicity, made the difference within Modern Art. Today, his impact is still remarkable, and his aesthetic simplicity and elegant choice of colours, have turned his work into a timeless legacy that inspires new designs. Architecture and fashion design are two of the main disciplines based on Mondrian’s paintings.

L: Jil Sander's design, 2012. R: Pablo Picasso, “Chouette Femme”, 1950, vallauris pottery.

Precisely, fashion has in several times resorted to visual arts to offer a new reading of artworks captured on fabric. Though in many cases, paintings have been taken as a reference for these designs (like Mondrian’s, that we have pointed out), here we bring the example of the pottery artwork by Picasso entitled “Chouette Femme”. The German designer Jil Sander based on this piece to the proposal that she presented on the catwalk in 2012.

L: Johannes Vermeer, “Girl with a Pearl Earring”, 1667, oil on canvas | R: A frame of the film “Girl with Pearl Earring”, 2003.

“Girl with a Pearl Earring”, by the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer, is a famous painting finished between 1665 and 1667 now kept in the Mauritshuis Museum in The Hague. Scholars consider this piece a “tronie”, a classic painting at the epoch, mainly made with a decorative purpose with no intention of identifying the person in the portrait. This was not a problem to the American novelist Tracy Chevalier, who based her book “Girl with a Pearl Earring” on this artwork. The writer builds a story on the relationship of the painter with a servant girl, Griet, that would be his model for this portrait. Years later, this novel was adapted to the cinema with an homonymous film whose main characters were Scarlett Johansson and Colin Firth. As a detail, we must point out that Vermeer felt an authentic devotion for these pearl earrings, and we can find them as little sparkling dots in other female portraits, like “Girl with a Red Hat” or “A Lady Writing a Letter”.

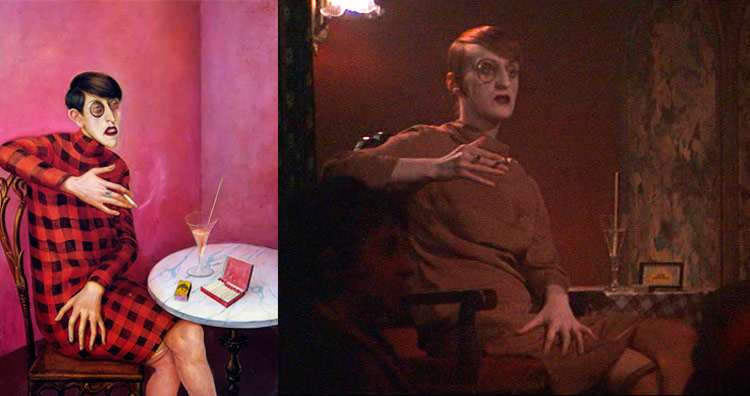

L: Otto Dix, “Portrait of Sylvia von Harden”, 1926, oil on canvas | R: scene from film “Cabaret”, 1972.

Cinema does not escape from the influence of the visual arts either. In this case, we talk about the film “Cabaret” (1972), whose first scene is inspired by the oil painting by Otto Dix “Portrait of Sylvia von Harden”, of 1926. The attention devoted to this film and the numerous artistic references that it has, besides of being itself an iconic film, explain that it was awarded the Oscar of Best Photography, under the direction of Geoffrey Unsworth. The choice of this pictorial reference is not casual at all. Otto Dix was one of the main representatives of the German “New Objectivity” trend, and this piece conveys some of the aesthetic principles of the epoch, especially in what the consideration of women against the imposition of beauty stereotypes concerns, at a period, the late 20’s, when the intellectual and female liberalisation mastered. Precisely, Otto himself asked Sylvia in several times to allow him to paint her. For the artist, this journalist and poet that frequented the Romanisches Café in Berlin, place where intellectuals and artists met at the time, summarised the purest essence of his epoch. It was not a wrong choice to inspire the opening scene of the film, also set at the beginning of the next decade.