ART ALSO JOINS THE FOURTH WAVE OF THE FEMINIST MOVEMENT

Oct 17, 2019

Breaking News

Several uprisings, protests and public initiatives demanding real equality between women and men in our society have given way to the so-called "Fourth Wave" of the feminist movement. We are starring in a historical period that defends that women's rights must be once again on the social and political agenda to settle a debt still pending on the much-needed parity. And in this context, the proposals that want to redeem the historical void that many women have suffered are of vital importance.

To some extent, this effort to highlight the different professional roles that many women have developed throughout history constitutes a titanic effort. We must keep in mind that this forgetting is not only due to a tendency to relegate them following the dictates of the dominant patriarchal thought, but also to a factual reality, such as the lack of women who could make their way into each historical stage and stand out in their field in adverse circumstances for this. Without a doubt, there would have been many more examples with a propitious context. Let us think that the world population is divided equally between both genders. Seen this way, throughout these centuries, our collective knowledge, our progress and the evolution of our own history has been deprived of the contributions that come from half of society.

As we said, we live in a stage in which projects rediscovering relevant female characters in their respective specialities are in full swing. The objective of these initiatives is not, of course, to change the past, but to open new paths towards the future. The questioning of our location on this path through equality is a reflection of a global society that has matured and that dares to take giant steps in this direction. Self-criticism and the will to amend imply a prior exercise of reflection and analysis. Thus, extolling the work of women who were pioneers in their field shows that history has not always been as they have told us, but, above all, it provides models and examples that can inspire the women (and society) of the future to face their personal and professional development with the certainty that they will not have obstacles because they are women.

Large institutions also add to this trend. The Prado Museum will open next October 22nd one of the most anticipated exhibitions of the year dedicated to two great women of painting who practically went unnoticed for the history of art. Sofonisba Anguissola (ca. 1535-1625) and Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614) were two outstanding artists who were able to devote themselves completely to their passion despite living in an adverse environment that prioritised male work. This exhibition brings together for the first time 60 works by these two authors and will be a unique opportunity to get to know their legacy. Although the relevance they reached in their time, even in life, was blurred over the years, in recent times a huge interest in their work has aroused, both for researchers, scholars and experts and for the general public. And this is because these creators broke moulds, dismantled stereotypes and questioned some of the maxims long defended by the society of that time about the lower quality of female work in artistic disciplines.

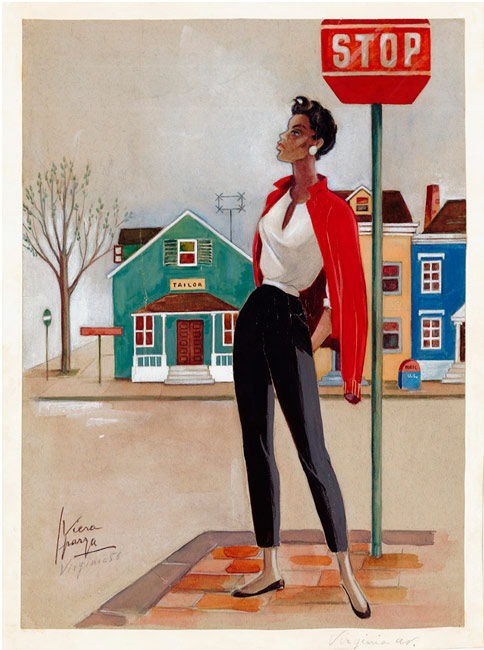

For its part, the ABC Museum of Illustration closed last month its exhibition "Dibujantas", which brought to light the work of 40 women illustrators who collaborated in publications since the end of the s. XIX that, however, remained anonymous on numerous occasions. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum also contributed to this line with an exhibition dedicated to women of the Russian avant-garde, under the title "Pioneers", which took place from March to June of this year.

These proposals fulfil an exemplary and pedagogical mission, with a discourse for equality developed from the position of influence that many of these institutions have, serving as a model for many others. Without a doubt, we are on the right path, walking towards a balance in all areas of society, and this not only applies to art but to any other sector of activity.