Art Madrid: Now that the maps are changing

Jan 30, 2025

art madrid

The contemporary art scene in Madrid, like the city itself, never stops evolving. Art Madrid, now in its twentieth edition, taking place from March 5 to 9 at the Glass Gallery of the Palacio de Cibeles, not only showcases the latest artistic trends but also invites us to question how we inhabit the world.

After a year of dedicated work organizing this new edition, we find ourselves at the peak of the process: the fair is about to begin. Having overcome the most challenging stages, we are fully aware of our mission—to be the platform that connects a vast diversity of artists with the public. We want their voices to reach you, whether through our communication efforts or your visit to the fair. This year, Art Madrid brings together nearly two hundred artists from twenty-seven countries, represented by thirty-four galleries from ten nations. From Taiwan to Mexico; from Cuba to Portugal; from Italy to Brazil; from Japan to Spain—tracing a route through the Dominican Republic, Peru, Germany, South Africa, France, the United Kingdom, Colombia, Uruguay, Venezuela, Belgium, Poland, the Congo, the Netherlands, Morocco, Argentina, Slovakia, Sudan, Austria, and Serbia. The wealth and diversity we are exposed to over these five days indicate that today's maps are shifting—or changing color, as the troubadour sings in that song. We are no longer talking only about physical borders; today's maps are fluid and transitory. They represent our identity, our memory, and our human connections.

The artists at Art Madrid, through works ranging from painting to installation, invite us to explore this uncertainty, to question ourselves, and, above all, to discover new possibilities.

Historically, maps have been tools for understanding space and locating ourselves in the world. However, today more than ever, those maps, like the territories they represent, are open to question—they have mutated, digitized, and fragmented. And as this happens, art continues to be the medium through which, paradoxically, we can find points of reference, direction, and meaning. Art Madrid, like other major events that reflect the pulse of contemporary art, is not immune to this reconfiguration.

In a sector that sometimes falls into inertia, we ask ourselves how to bring together so many perspectives, styles, and discourses in the same space for five days. That question leads us to a broader reflection on the geographical and ideological boundaries we inhabit today.

The thirty-four participating galleries introduce us to a universe of creators who, though diverse in technique and approach, share a common concern: the need to reinterpret the world from new perspectives. What once seemed immutable is now in constant flux. Globalization, technology, politics, and the climate crisis have altered the maps that once guided us. But in every change, there is an opportunity—a territory for creation. And that is where art comes in: as a vehicle for imagining new cartographies.

Maps, like identities, are constructions in constant evolution. Instead of marking borders, art today invites us to erase them. With more than thirty international galleries in attendance, Art Madrid reinforces its global character and its ability to transcend geography. Here, artists do not work on pre-existing maps; they reinvent them with each creation.

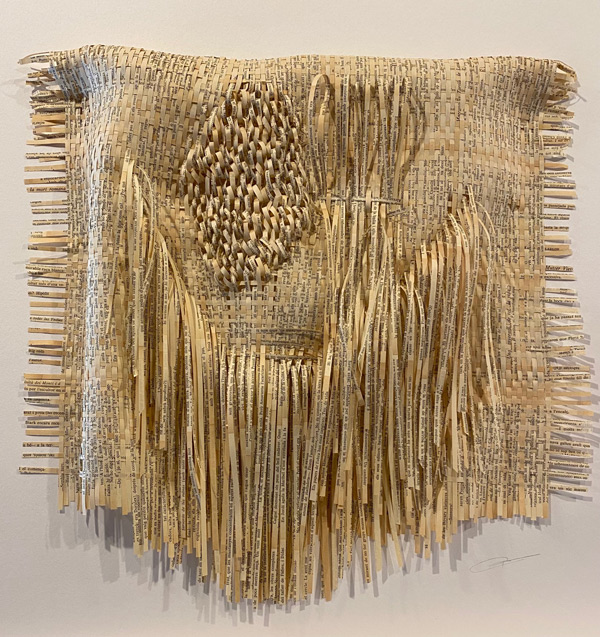

The works presented at the fair are not confined to a single medium. Through painting, sculpture, installation, and new technologies, artists explore how we position ourselves in a world where traditional structures are increasingly fluid. They do not seek easy answers but pose essential questions: What does it mean to belong to a territory today? How do globalization, the climate crisis, and the digital era affect us?

Art Madrid becomes a space where creators engage with the major questions of our time—from the geopolitical to the emotional. Their works are not just meant to be contemplated; they provoke, shake, and transform.

The borders of art, like those of maps, are no longer fixed. That is the challenge the fair presents this year: to question them, expand them, and redefine the role of art in a constantly changing world.

In this reconfiguration, Art Madrid positions itself as a space where the voices of contemporary art help us redraw the map of humanity, both in its physical and emotional dimensions. Because today, true borders are not just geographical—they are also cultural, digital, and symbolic. And being an open window to that experimental exercise that is making art, is precisely the space where those borders can be subverted and even crossed.