ART MADRID-PROYECTOR'22 PROGRAMME

Feb 9, 2022

art madrid

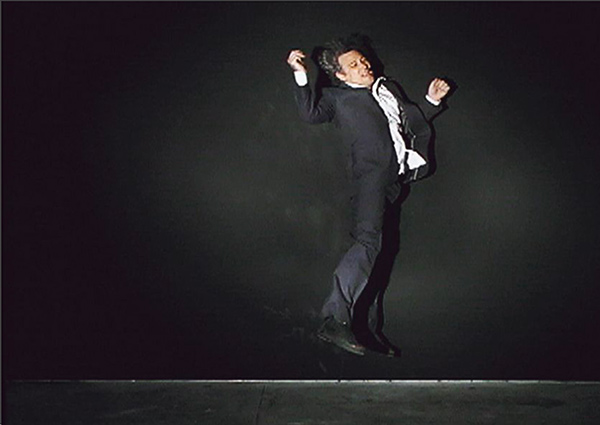

For this new edition of Art Madrid'22 the video art platform PROYECTOR, once again under the curatorship of Mario Gutiérrez Cru, proposes a programme that revolves around the concept of loop. During the fair, the ARTMADRID-PROYECTOR'22 stand will allow us to enjoy a proposal by the pioneer of new media art Gary Hill together with a performance on 23 February at 8 pm. On 25 February, the pioneer of Spanish sound art Llorenç Barber will close the fair with a performance at 20:00h.

Pioneers" professional meeting

On the other hand, on Saturday 19 February in the Sala Auditorio El Águila at 12 noon there will be a professional round table organised by PROYECTOR on the concept of "loop" in video art, new media, festivals and media collecting.

We will have Gary Hill (usa), pioneer of new media art; Tom Van Vliet (hol), collector and director since 1982 of WWVF, one of the first video art festivals in the world; Sandra Lischi (ita) director of Ondavideo and INVIDEO, pioneering video art festivals since 1985; as well as the presentation and moderation of Tamara García (spa), specialist in the concept of the loop.

The meeting will be held in English, without translation, and can be watched both in person and virtually via streaming. A video with subtitles will be uploaded afterwards on the fair's channel.

Screening of international curators

After the professional meeting in the morning, several of these experts will present a historical selection of video art. Tom Van Vliet (hol), collector and director since 1982 of WWVF, one of the first video art festivals worldwide, and Sandra Lischi (ita), director of Ondavideo and INVIDEO, pioneering video art festivals since 1985, will each present a 40-minute curatorial presentation of works from 1978 to 2003.

We will also have a presentation, this time online, by Irit Batsry, also a pioneer of video art and director of Loops.Lisboa and one of the components of the international project LOOPS.Expanded, which is an international network dedicated to exhibiting and investigating the concept and form of the Loop. With the aim of experimenting with decentralized video art / moving image exhibitions, symposiums, talks and masterclasses.

The network, founded in 2019, expands the original Loops.Lisboa initiative that started at the National Museum of Contemporary Art MNAC in Lisbon in 2015. The founders of LOOPS.Expanded are curators and organizations in the field of video art from five different countries: António da Câmara (Duplacena / Festival Temps d'Images, Lisbon - Portugal), Mario Gutiérrez Cru and Araceli López (PROYECTOR, Madrid - Spain); Sandra Lischi (Ondavideo, Milano - Italy); Tom Van Vliet (WWVF, Amsterdam - The Netherlands); Jaqueline Beltrame and Alisson Avila (collective Cine Esquema Novo (Porto Alegre - Brazil) and Irit Batsry and Alisson Avila (Loops. Lisboa / Festival Temps d'Images, Lisbon - Portugal).

Also, to close a day dedicated to video art, the artist Lina Jiménez Nampaque will give a live performance at 19:30h in the same Sala El Águila.