ART WITH BOOKS AND BOOKS WITHIN ART

Apr 25, 2019

Breaking News

Books are much more than just an object. Its content is capable of housing infinite universes, of being an inexhaustible source of knowledge and transporting us to real and unreal places where the imagination reigns, from another time, from another dimension. It has been shed blood because of the books; there has been prohibition, censorship, repression and annihilation. They have also opened doors to freedom, exchange, tolerance and knowledge. Such is the power of a book, which has become an object of worship. Who has not opened a new book in a bookstore and smelled its pages? We like to read them, see them on our shelves, order them, leave them open face down, carry them in the bag, read them on the subway, lend them, ask for them, return them, and give them a second life. And this same passion is shared by many artists who make books their raw material of work.

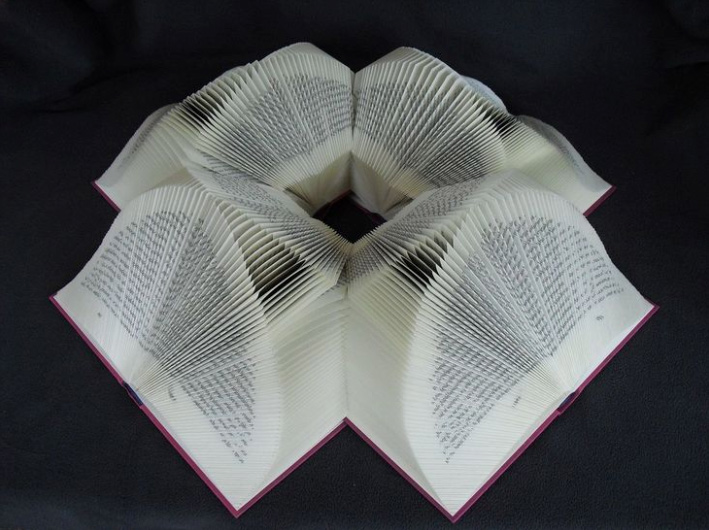

The artist Schaduwlichtje is able to transform printed pages based on folds. This way, he manages to create these amazing sculptures with no need for scissors. This Dutch mathematician began working on paper when he joined the bookstore Books4life as a volunteer in 2013.

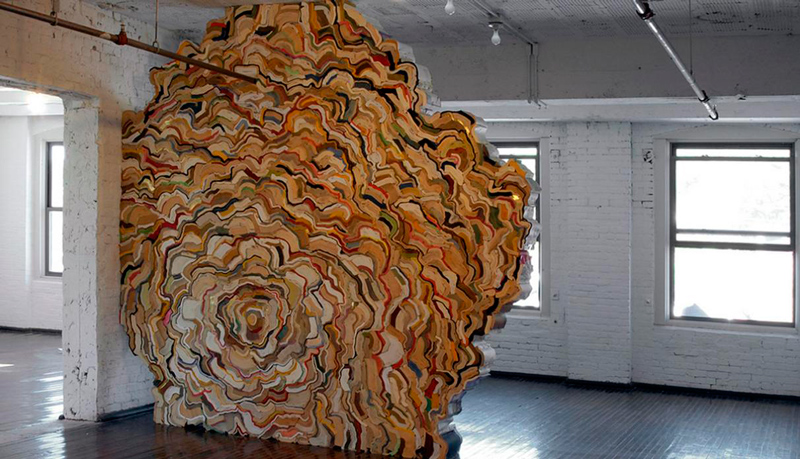

Other authors focus on taking advantage of the outside of the books for their compositions. This is the case of Mike Stilkey, an artist who works with used and discarded copies to create huge walls of stacked books on which he applies paint to create his works. Sometimes, the colour of the cover determines the type of piece you are going to draw. His compositions are intriguing and overwhelming.

For his part, Jonathan Callan reuses magazines, fanzines and books as the main element. His works give a second life to these materials eliminating references to their original use so that he bends the leaves and curves the covers to get some abstract compositions with shapes that remind us of the organic structures of the coral or the way lichen grows in the bark of the trees.

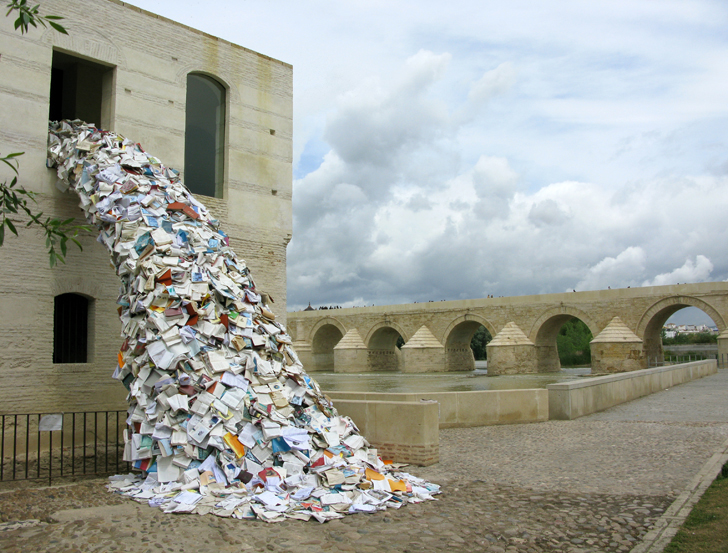

The work of Alicia Martín is well known. She has been using books in large-format sculptures for years to create proposals with enormous visual impact. In the form of a waterfall that springs from a window or as a huge spiral that imitates a whirlpool of water, her pieces surprise and charm equally.

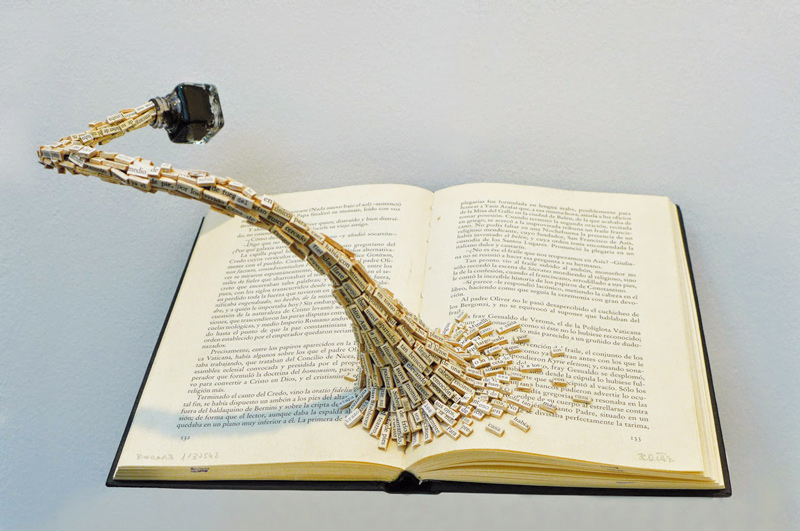

Much more subtle is the work of Beatriz Díaz Ceballos. Her work is based on the written word, and she uses books as an infinite source of printed texts from which words sprout in waterfalls. Her proposals resemble allegories of a fairy-tale that refer us to images of fantasy and reverie.