NACHO ZUBELZU: NATURE IN ALL THINGS

Feb 3, 2024

art madrid

ARTE & PALABRA. CONVERSATIONS WITH CARLOS DEL AMOR

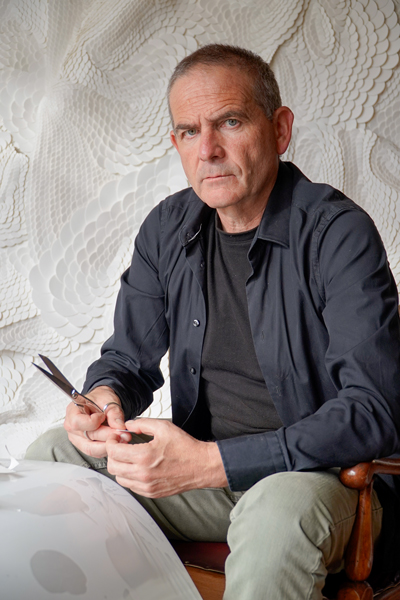

Nacho Zubelzu (Reinosa, 1966) is an artist who, from his Valle de Campoo in Cantabria, decided one day to travel the world with this valley in his backpack, and that it was nature that surprised him and entered into all his work.

Artists who love nature should remember that it is extremely changeable, even more so when you are a nomad and you have to respect it because there is only one. This respect and this interaction with the environment make Zubelzu's work subtle, deep, virtuous and emotional, because the earth is an emotion, but to get excited you have to live it. He lives it with the greatest respect and commitment, he lives it so much that he often makes the transhumance with the shepherds of Extremadura and Andalusia, who take the cattle in search of that second spring that I wish we humans could also live.

When we move, we leave our traces, whether we want to or not. The important thing is to be aware of this trace, which will be inherited by those who do not yet know it.

We are in the presence of an artist whose first commandment is balance, whose second is observation, and whose third is curiosity; and who, by means of drawing, sculpture, photography, or performance, tries to change the way of seeing of those of us who move too fast to understand that there is only one world, from which we seem to be moving further and further away.

If you had to define yourself in one sentence, how would you define yourself?

I would define myself as a nomadic artist who moves back and forth. I think I am a creative, a lover of nature, which I then transform, like a shaman, in my travels. I want to bring art closer to life, to our roots, to the universe. In short, I see myself as a mediator between man and the earth.

My second question is probably related to the first, because I don't know if I should introduce you as a painter, a sculptor, a performer or even as a surveyor and shepherd. Help me.

As you say, I had already summarized it in the first question, but I consider myself a man of rebirth, like those shepherds of the simple life that I have known, who always find solutions to survive with the minimum resources. A shepherd once told me that all you need to go on living is a spoon and a knife. And indeed, I don't like to pigeonhole myself into one particular discipline. I like to embrace them all. I feel very comfortable using different resources or tools to create, to excite, to make people feel, and to try to reach the viewer, which is ultimately the great challenge. For all this I use different artistic disciplines and I think that the world is a huge palette full of resources, ideas, materials. My job is to select, organize and decontextualize them in order to find the key, the solution, in short, the work. To do this, I will use the discipline and the tool that best suits the moment and the place, be it carving, painting, drawing, audio-visual media, or even my own body. So, Carlos, how do you define me or what do you call me, as the other one said, "don't call me Dolores, call me Lola".

Travel, movement, observation, places and traditions are elements that are reflected in your work, right?

PYes, that's true. Observation has been the key to many of my projects. Since my childhood and adolescence, I have spent many hours in the countryside, waiting, observing the rural environment, the animals, and their behavior. I was very passionate about migration, both of birds and mammals. I think that's where the journey and the interest in this activity, in transhumance, came from. It's a point of origin that fascinates me, and that's when I concentrate all my artistic potential to reflect on this particular subject. I have experienced transhumance in the first person. I have participated in several transhumances throughout the peninsula, from Andalusia to Teruel, from Extremadura to the Cantabrian Mountains, from Albarracín to Sagunto, well, countless transhumances. And in these journeys I have shared and lived with shepherds and cattle for many months. I was able to nourish myself and absorb all this essence, this impressive aesthetics. It is an intense way of life, in full contact with nature, with the environment itself. And I was able to collect and reflect all these experiences in the series called Trashumancias. It was, and still is, a great work of simplification and search, to achieve above all the expression of the bucolic, the simple, the beautiful movement of large herds, sometimes thousands of animals, sliding, moving in unison on slopes, mountains and ravines. I am really very happy with the result of this project and I am still working on it. As with transhumance, I try to reflect on each culture, each civilization I come into contact with. I absorb their philosophy, myths and legends, which I then have to simplify and apply to my own artistic work. I always say that life is an accumulation of experiences and circumstances, and that the journey itself encompasses all of them. Maybe it is because life is a great journey.

There are artists who flee the place of their birth and are always searching, but you seem to be always searching through your travels, but from a specific place that transcends everything, which is the place where you were born. How important are your origins to what we see?

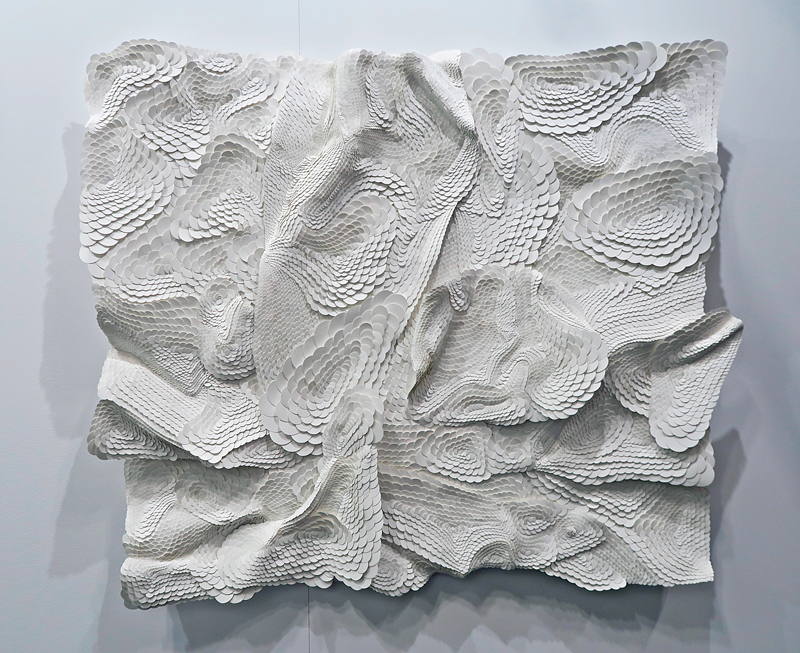

Well, I think everything is in my origins. Curiously enough, I was born in a car before arriving at the hospital in Santander, in Valdecilla, and I have always said that my love of traveling began there, in a two-horse cart. In my childhood memory are implanted: the memories, the senses, the environment, the experiences that emerge and I, as an artist, I have to be always attentive to be able to use them in the artistic process. I have been particularly influenced by the territory, by the rural environment of my grandparents, by nature, by the countryside, in short, by all the mountains of the Campoo Valley in particular, which is the territory that surrounds me here in Cantabria. I have also been influenced by the climatic conditions, often harsh, such as cold or snow, with regular snowfalls, sometimes one meter, one and a half meters, since I was a child. For this reason, I think I often use the color white, always looking for its shades and brightness; and also the ephemeral movement that they make and that is never repeated in the accumulations of ice and snow; very evident in works such as La piel de las montañas or Cristales de hielo. I also drew a lot of wood intuitively. I was fascinated by the aging process, how the gray colors that the wood takes on age. Also the burnt wood that I saw in the fireplaces and kitchens in the villages. Obviously, in addition to the aesthetic conception of the environment in which one was born and lived, this environment conditions the use or not of some or other materials. In my case, everything that surrounded me, leaves, bones, skins, hair, petals, any non-artistic element, I used it, I studied it, I took it out of context to then create my pieces. I think that's also where I got my interest in the ephemeral, like nature itself, all its cycles, its seasons. I think that's how I got into Land Art, using nature, the natural environment and the territory as a support for a lot of my pieces. And also using, starting to use the performance, my own body in the pieces. Sometimes more conceptual and defensive pieces in defense of the environment that I have always wanted to preserve, which is the one that surrounds me.

Curiosity drives your work, and curiosity drives you to keep exploring. This process of always trying to move forward, not staying in comfortable places, must also be exhausting?

Of course I am always trying to move forward, to discover and investigate. It is a constant in my life to connect objects and places in different cultural contexts and also in different countries. For example, I can sew Chinese paper with Peruvian llama wool or sow my body in the Atacama Desert. Or gilding in the Kintsugi project, where I made a “manyatta Masai” in Kenya. And my work is also very handmade. I always want the artist's hand to intervene, as do the artisans in those atavistic cultures that I have known in Africa, South America or Asia, and that have always captured me with the ancestral power that they have. So the work I do is always meticulous, patient, forming series, repetitive elements, often superimposed. What I want to represent in itself is the order that exists here in nature, which comes from the wing of a butterfly, the wing of a bird, or even in botany. The way can be by cutting, sewing, drawing with a pencil or forming. The result always tends to be balanced compositions that seek the aesthetic perfection that nature has, but it is very difficult to get there. I think that when you are in that moment of struggle, of difficulty, of uncertainty, that is when you really develop the activity, intuition appears and... wham! the key appears, the spark, I say, the solution to the work. It is necessary to be "on the wire" many times, not to be accommodated, so that the ideas, the resources, the decisions appear. On the other hand, I think that routine completely kills creativity, or at least relaxes it. And yes, Carlos, I can tell you that it is quite exhausting, this permanent restlessness, curiosity, searching, but then the satisfaction and the joy, the pleasure of this creation, you will know it too, far exceeds all the effort.

What fits into your universe?

In my universe there is room for a lot, there is room for almost everything. There is room for sincerity, both in the person and in the work. There is also room in my universe for "the three T's" that I say and that I consider fundamental to creation, which are Trabajo, Tiempo y Talento (work, time, and talent). There is room for tolerance, respect, humor, there is room for children. And of course, what always fits for me is lying down, spending the night in the country, looking up at a sky full of stars, listening to the song of the tawny owl in the mountains of the country. That always fits.

And what doesn't?

Well, there is no place for fanaticism, envy, mediocrity, routine; in other words, there is no place for the opposite of what fits. And of course it does not fit, and we have to fight for it, a planet full of plastic, of pollution, that does not breathe and that this year has risen one and a half degrees of average temperature. Unfortunately, in my travels, I have been able to verify that plastic has reached every unexpected corner of the world. Just like football, isn't it? Even to the most inaccessible places. I have seen it in the Amazon, in the Himalayas, in the Masai Mara, in the Mekong Delta. That's what doesn't fit into my universe.

Where do you think your art will go?

Well, I think my art is going, and if it is not, I will try to make it go, where I can continue to enjoy it and where people can enjoy it and be moved by it. I also want my art, within my responsibility as an artist, to serve in some way to improve the human condition, as well as to alert and denounce the worrying social and environmental situation we have on this planet. Within these premises, I will continue to develop artistic processes already initiated, in which I see a lot of potential and in which I have great illusions. For example, Adorando, a project in which I will gold parts, objects, broken or degraded places of the planet, based on the Japanese Kintsugi project. Of course, I will also follow with the same enthusiasm the Trashumancias series in its different versions and formats. It is the project I feel most comfortable with, and I believe it gathers and develops my whole surrounding universe. As well as the performances, and I will continue to do so with Sembrándome, which I carry out in different parts of the world to draw attention to the need to preserve the humanities, the arts, literature, poetry, so that they are not so much absorbed by science and technology, especially today with the worrying advance of artificial intelligence. At the same time, I continue to develop the Deucalionic Pirra project, in which I hide various anthropomorphic lead figures underground and place them in different parts of the planet. Through the Metro Gallery, which has bet on the project, collectors are responsible for retrieving what I call "clay seeds", which contain the coordinates and information about where the figure is. I think it is a different way of acquiring a work of art and, in this way, involving the buyer in part of the creative process, in the completion of the work. There is a great adventurous, playful, childish, archaeological and even anthropological component to the process. I am also very involved and very excited. In short, through my art I want to continue to leave traces of tolerance, respect, and if possible, though difficult, peace around the world.