CENSORSHIP IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Dec 21, 2017

calendar

Balthus, “Thérèse Dreaming”, 1938. ©Photo by Oliver Berg/dpa picture alliance archive/Alamy.

The Metropolitan Museum of New York has recently faced the harsh decision of whether or not yield to social pressure to dismiss from the exhibition a painting by Balthus considered "sexually suggestive". The work is "Thérèse Dreaming", concluded in 1938, which portrays a young girl at her 12 or 13 years in a position that for the critical eyes of the New Yorker Mia Merrill was totally inappropriate. This led to an online campaign that gathered more than 8,600 signatures requesting its withdrawal when the same work had previously been exposed in Museum Ludwig in Cologne without any setback.

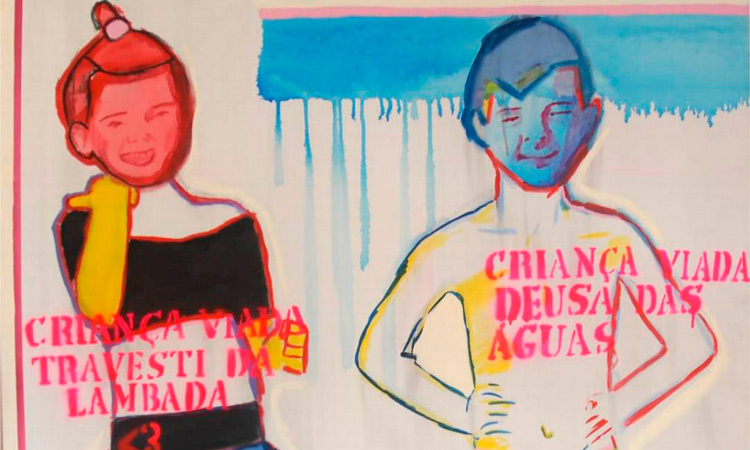

Bia Leita, "Travesti da lambada e deusa das águas", 2013.

Another recent case occurred this summer at the Cultural Center of Santander in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The exhibition entitled "Queermuseu" gathered more than 230 works by 85 Brazilian artists around a project that explored the artistic communication and representation of homosexuality and non-orthodox sexuality. The controversy sprang up a few days after the inauguration, and the social pressure by a group of ultra-right-wing demonstrators and evangelists led the Santander Foundation to close the show. The case was then brought before the authorities who, after carefully examining all the works, came to the unanimous conclusion that none of them had traces of paedophilia.

Detail of “Reclining Nude” by Modigliani in Bloomberg TV and The Financial Times.

In November 2015, the work "Reclining Nude" by Amadeo Modigliani was auctioned at Christie's New York, at that time the second most expensive artwork in the world. Chinese collector Liu Yiqian bought the painting for 170.4 million dollars. The curious thing about this situation is that some media applied to the spread of the news a flagrant censorship that concealed or blurred the most sensual parts of the painting, perhaps to flaunt a decorum and restraint adapted to the general feeling of its subscribers.

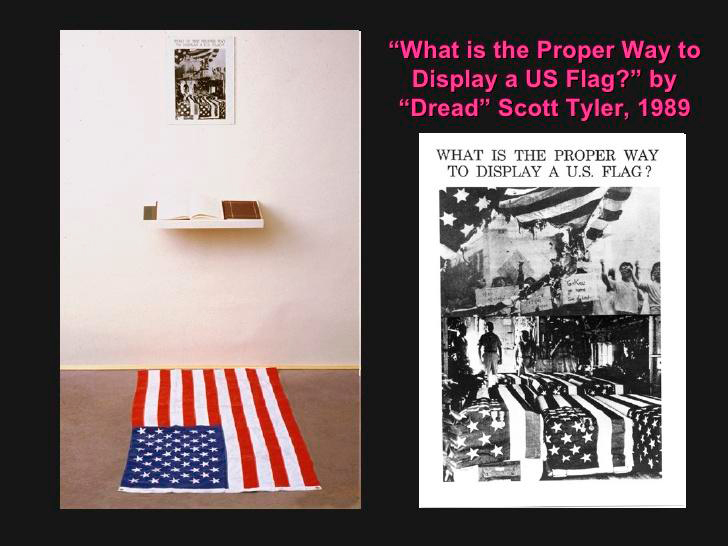

Dread Scott Tyler, “What is the Proper Way to Display the US Flag?”, 1989.

Without forgetting the case of the Russian singers Pussy Riot who recorded their hit against Putin in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior of Moscow, and ended up in jail, or the decision of the MACBA to cancel the exhibition "The Beast and the Sovereign" in which one of the central pieces was the proposal of the Austrian artist Ines Doujak, in which a King Juan Carlos was sodomised; the censorship of political overtones underlies some of this cases. Another example is the installation of artist Dread Scott Tyler on what is the proper way to display the American flag. In the work, a US flag lying on the floor was placed in such a way that in order to read a protocol manual one had to step on it. This led to the arrest of several visitors for outrage and the artist himself for violating the law of protection of the flag of 1989.