COME WITH US TO KNOW THE FRACTAL ART

Oct 22, 2018

Breaking News

Talking about fractals usually refers us to geometric patterns related to the golden proportion that nature offers in its immense variety. Discovering something that was already there and to name it is, though surprising, something very recent. Thus, the fractal concept is not new for mathematics, which already studied it in detail at the beginning of the last century within the theory of measurements; nevertheless, the specific name was not used until 1975 by the mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot, who distinguished several types of fractals according to their greater or lesser accuracy in the copy and the possibility or not of infinite reproduction.

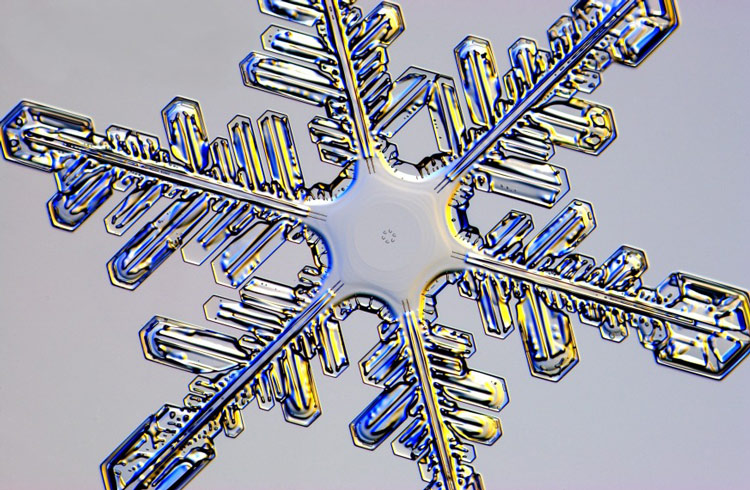

But what do we understand by fractal? The word was used to designate the patterns of forms that did not fit the traditional geometric descriptions despite keeping an ordered structure. A proximity analysis revealed that these patterns were composed of small elements equal to each other, composing drawings that repeat on a larger scale, keeping the same distribution. Nature is full of examples of this type, such as snowflakes or sunflower seeds.

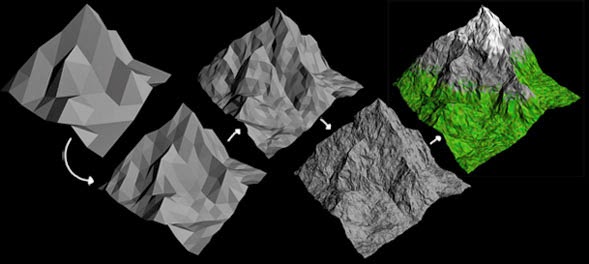

The study of this concept had an immediate practical application to graphic design. The use of fractal structures in the clouds, the mountains or the sea gave the graphics a greater realism that significantly improved the final result. Likewise, music is full of fractals and many classical works by Beethoven, Bach and Mozart work with this concept in their compositions. With the constant presence of these patterns in our environment, although unnoticed for a long time, very soon this interest made the leap into art. The plastic transposition of this idea opened a world of expressive possibilities still to be explored, even more in abstract works, where the game of geometries seemed to be running out.

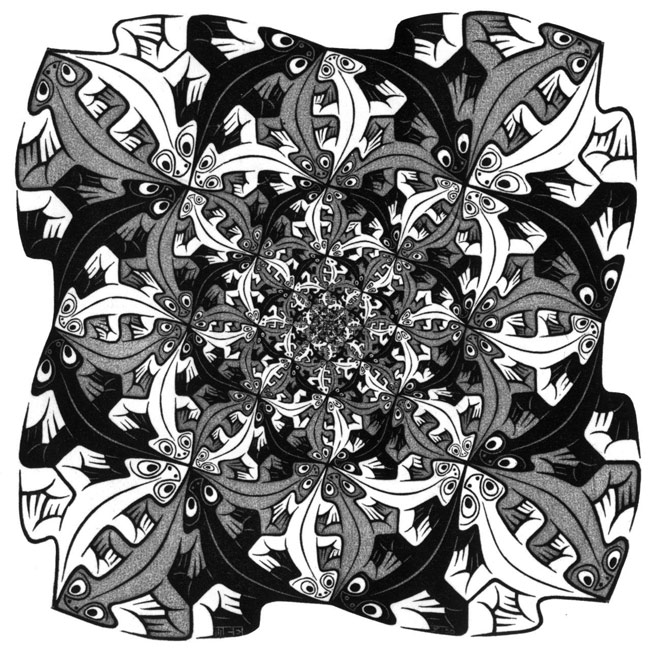

Among the first artists who worked with this concept, we must mention Escher. His production is difficult to classify, although there is a clear interest in drawing and engraving, with which he channelled his intellectual restlessness and expositions of opposite terms, like the infinite versus the limited, the black and white, the misunderstandings, the double reading symmetries... Although the most famous works of this author are those that present optical games and visual paradoxes, he also investigated fractals with works that synthesize this concept perfectly, even though it had not been first used yet.

Jackson Pollock's painting is also said to contain an infinity of fractal structures. The fascination that this artist has always raised, with such a short life and such a large production, led Australian scientists Richard P. Taylor, Adam P. Micolich and David Jonas to undertake a detailed study of his work in 1999. The work of this representative of abstract expressionism bases on the technique "drip and splash", drawing lines and spots by dripping and throwing paint on the canvas. The conclusion is that the fractal proportion of his painting increases with the years and gains perfection, and thus, we keep the same chaotic sensation of spread pattern whether we observe a detail of one of his works or the piece as a whole.

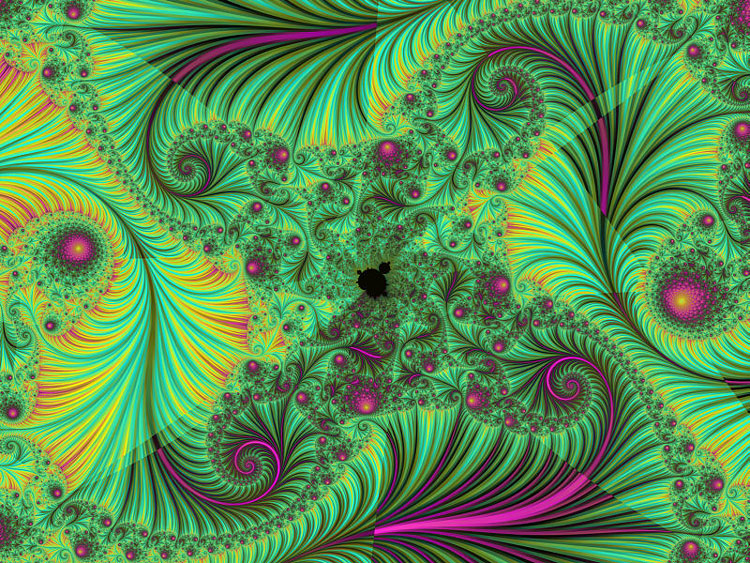

Beyond these examples of traditional art, many contemporary creators approach their works from computer-made compositions where the presence of fractal algorithms combined with the changes of colour originates shocking images. For this reason, fractal art appears intimately connected with computational art, a new trend in which creators who usually have a previous background in the world of science or computer science stand out. We can mention as examples Scott Draves, William Latham, Greg Sams or Kerry Mitchell.