CURIOSITY + X-RAYS + ART: THE PERFECT COMBINATION

Nov 20, 2018

Breaking News

At a time when visual arts seem to have exhausted much of the traditional resources, artists dare with new techniques and methods to enter an unknown soil where everything is possible. Thus, there is room for surprise, innovation and exploration, in a novel and, at times, risky forms of expression.

One of these examples is the resource to X-rays to capture images. The use of radiographs in art is not entirely new, although its applications have been mostly for study purposes, to discover the invisible layers of paintings, analyse pieces in authentication processes or look for hidden brush-strokes of the great masters, with the will to better understand their creative process. The use of this technique for genuine artworks, however, is quite recent, but its appeal is such that some artists have specialised in imitating the aspect of an X-ray in their proposals, as so the Londoner Shock-1 does.

Beyond the curiosity of analysing objects from their deepest layers, the truth is that its visual impact allows getting unexpected results, with an undeniable artistic potential. This is the path that some creators have followed, in which some have ended only by chance or derived from a professional speciality that is in direct contact with this technique. For this reason, many authors of radiographic art are scientists or doctors who have known to see in their daily images a different creative application. We share some of their proposals with you.

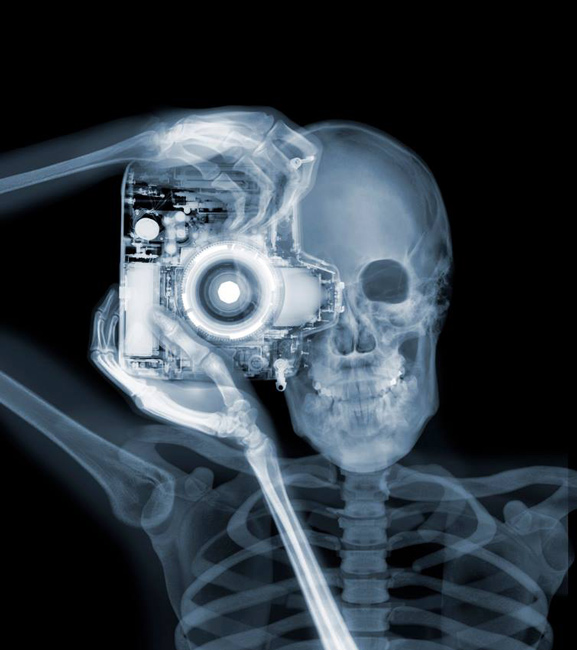

Photographer Nick Veasey explores a more human and active side in his proposals. The use of X-rays for this author has a more analytical and less compositional aim. As he himself explains, his work tries to transcend what’s visible in a world dominated by the image. This way, all the connotations that we associate with an ideal appearance of wealth, power or status dissipate. He aspires to look for what is beyond, in the essence of what makes us equal, while revealing hidden details about structure, form or movement. His photographs are fascinating and captivating.

Arie Van't Riet is a medical physicist who ended up making art through X-rays. In his interior studio, provided with three X-ray machines, he composes his floral still lifes, in which the elegant delicacy of the petals, the transparency of the leaves or the fragile structure of the butterfly wings are always visible. The of Van't Riet combines this work with a digital colouring task, to give rise to these images full of harmony and balance.

Steven N. Meyers moves in a similar way, although this author dismisses digital colouring in his compositions. In that sense, his work is more naturalistic and offers results closer to traditional screen printing or lithography. But what he also shares is the search for balance in the image. His choices are never left to chance. There is a serene elegance based on the structure, the staging of the elements and the purity of the light. Therefore, the whole of his work manages to convey a great hidden beauty.