Esther Ferrer: an artist of performance

Oct 25, 2017

exhibitions

Esther Ferrer, 2012. Photo ©Publiescena.

Esther Ferrer was a pioneer in the art of performance, precisely at a complicated historical moment in terms of freedom of thought and expression. Her figure stands out not only for the fact of entering into the artistic action as a form of manifestation but also for being a woman in an eminently masculine context.

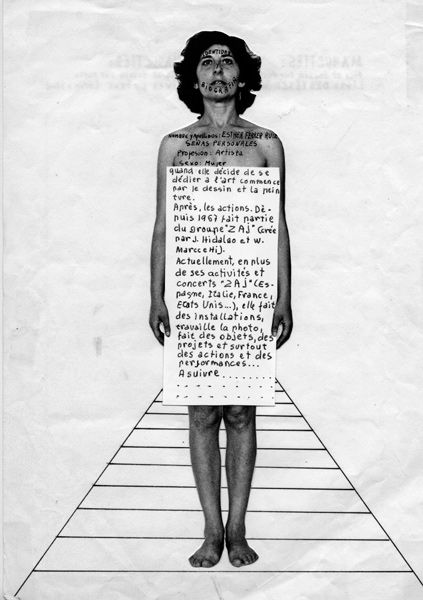

Esther Ferrer, Biografía para una exposición, 1982. Collage. Photography and ink on paper.

Esther joined in 1967 the group Zaj, along with Ramón Barce, Walter Marchetti and Juan Hidalgo. It was a transgressor and critic collective who, however, knew how to break through in the 60s and 70s and offer a multitude of artistic performances, even before they were named as such. Faithful to its Decalogue, Zaj organised actions in numerous Spanish cities but never allowed their performances to be filmed. As Esther, herself explains, "I have never asked for help from the Franco regime or tried to participate in anything they organised." They wanted to maintain their independence.

Incidents at the Teatro Gayarre during the performance of Zaj in the Encounters of Pamplona, 1972. Via: lajuntadecarter.com.

Settled down in France for many years, a country where she has lived more than in Spain, she worked as a journalist and translator for Gallic media specialising in art with outstanding collaborations in El País or Lápiz magazine. This creator has always been concerned with pedagogy and the role of women in society. In fact, she educated in teaching and pedagogy. She founded with José Antonio Sistiaga a school focused on promoting free expression of children, based on the method of the French pedagogue Freinet, whose technique gives absolute freedom to children from the creative aspect.

Esther Ferrer, Canon para siete sillas. Performance, 1990.

The Reina Sofía exhibition, titled "Todas las variaciones son válidas, incluida esta", offers a tour of her artistic career and focuses on the analysis of the author's own creative process, very interested in representing the passing of time, the changes of the body, and the mobilisation. She lives all these questions in the first person and, although she tries to be objective, she recognises that there is always something of ourselves that sneaks into our expressions.