Exhibition Le Corbusier, an atlas of modern landscape in Caixa Forum Madrid.

Aug 20, 2014

art madrid

|

CaixaForum Madrid hosts until October 12 a special exhibition devoted to this creative, organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in collaboration with the Fondation Le Corbusier in Paris.

The exhibition offers a truly vital tour through Charles-Édouard Jeanneret's life with his early influences at his birthplace, in La Chaux-de-Fonds (Jura, Switzerland., 1887), and tracking of all his movements at the planet, which had a great influence on his work and his concept of architectura and urbanism.

|

|

|

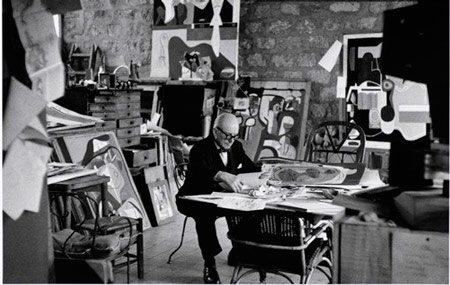

Jeanneret was more than an architect and furniture designer, was also a painter, writer and photographer, and, moreover, was a visionary, critic and ambitious, whose revolutionary projects were breathtaking for everyone. But what it was most fascinating in his works was the idea of questioning the status quo and ambition as a radical change in concepts, starting with the material used itself and following the organic character of the buildings. In 1920, already established in Paris, founded with poet Paul Dermée magazine of art and avant-garde culture L'Esprit nouveau, where he began signing his articles with the pseudonym Le Corbusier, not to link your real name to provocations contained in his writings.

|

|

|

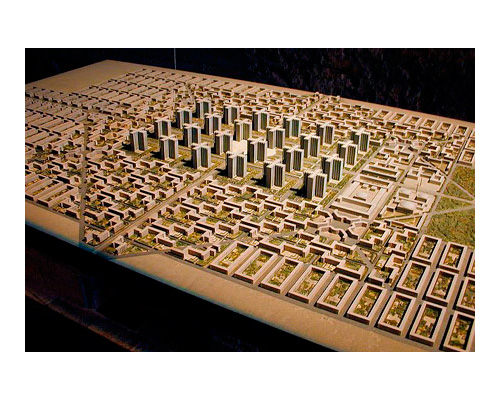

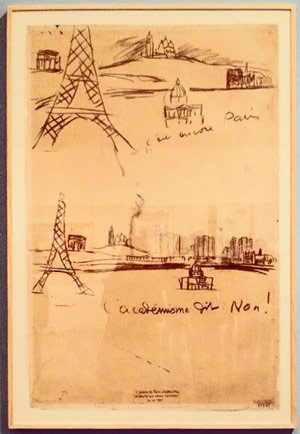

Its buildings are the aesthetic lines of the 50s, however, the zenith of his creations blossoms between 1920 and 1930 never would have said that some of their best ideas are from this period, but it is. The commitment reinforced concrete housing construction modular and expandable and movable plates, the vast redevelopment projects of European capitals ... The ideas of Le Corbusier soaked all their architectural conceptions and in them was always the deseeo of espetar dialogue with the landscape and the environment, and create a magnificent work which incorporate all the good that had been collecting throughout his many travels abroad. From this period are the groundbreaking proposals for redevelopment of the center of Paris or Moscow Kremlin, projects that never saw the light.

The insatiable ambition of Le Corbusier not always (or rather never) coincided with the desire for change or reform who had to approve their projects. Le Corbusier was busy, tireless in attack the obsolescence of these thoughts and the obtuse and limited character who cercenaban, again and again, his view of revolution and urban transformation. Few of his extraordinary complete renovation projects were carried out, and that fruited did outside Europe. Indeed, Le Corbusier was almost bound to an intellectual exile. In his many lectures, in which he drew while setting out his ideas, to the amazement of the audience, did not hide his disappointment with the impositions of power and constant denials that he was a victim.

|

|

|

Le Corbusier did not hesitate to go to South America, Africa and Asia. However always dreamed of returning to Europe. And he did, accepting projects

lesser importance in which he could also implement some of his ideas, such as building known unités d'habitation, modular homes designed to facilitate the building and be functional, or designs in harmony with the landscape, such as the well-known chapel of Notre Dame du Haut, Ronchamp.

In recent time, Le Corbusier became melancholic and nostalgic, and drastically reduced its activity, taking refuge in his painting studio at the foot of the Mediterranean, to live with what he called "my island".

|

|