FROM THE CANVAS TO THE MOVIES

Nov 7, 2018

Breaking News

The coexistence of the arts is, more than a fact, a necessity. Inspiration calls for inspiration, and it is difficult not to surrender to the beauty of some works that have passed into the history of art as an essential. That’s why it is not strange that cinema, the art of image par excellence, look for its models in some iconic artworks. Beyond the films about the lives of the most famous painters, there is also a less perceptible, more meditated influence that comes to light among film-frames to recreate imperishable scenes.

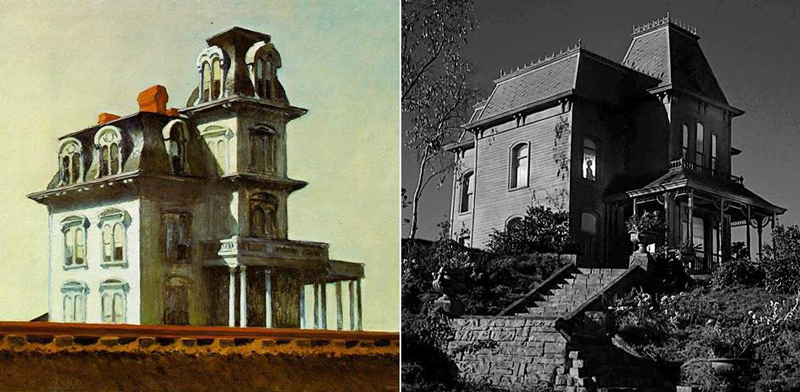

One of the easiest references to identify is the house of Psycho (the genuine one, the Hitchcock's masterpiece), directly drawn from one of Edward Hopper's paintings. The resemblance is huge, and although the architecture is not identical, both the framing and the environment refer us immediately to the work of the American painter.

Emulation is not exclusive to the first years of the 7th Art. The current cinema, in a context of overabundance of special effects, fantasy worlds and supernatural powers, seeks to consolidate its artistic language with productions of exquisite photographic composition based on masterpieces of the history of painting. To give just a few examples, we can mention Dunkirk (2017), with instants inspired by "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" (1818), by Caspar David Friedrich.

Classic paintings have always been a source of inspiration, especially if the reference is known worldwide. So it is with this scene of "About Schmidt" (2002), by Alexander Payne, where Jack Nicholson languishes in his bathtub in the same way as the famous painting "Death of Marat" (1793) by Jacques-Louis David.

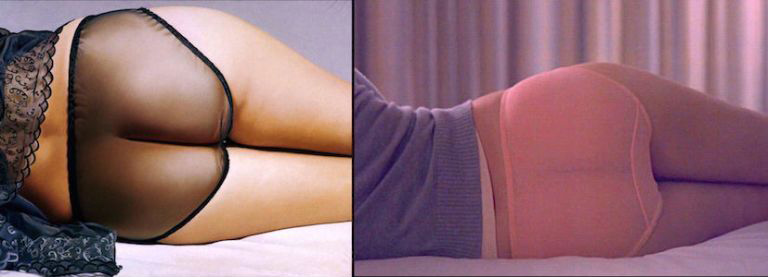

The references are also taken from contemporary art. The beginning of "Lost in translation" (2003) by Sofia Coppola, is identical to the work "Jutta" (1973) by John Kacere.

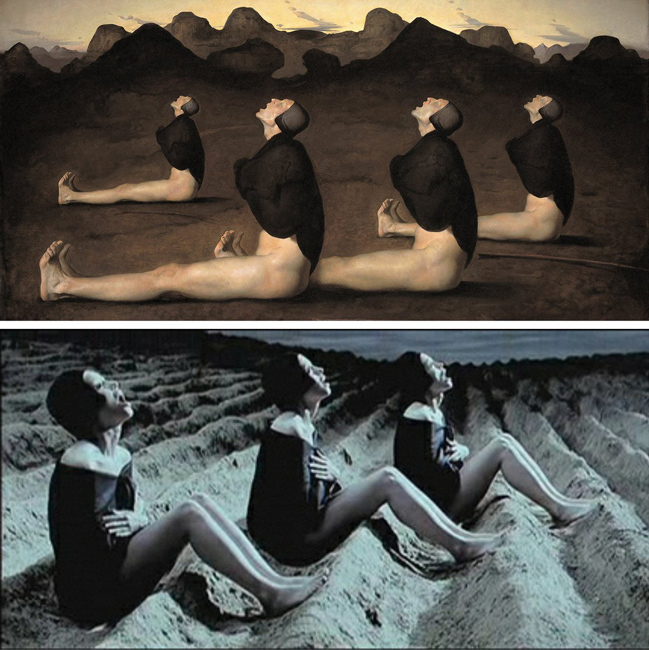

And we can also mention the painting by the Swedish artist Odd Nerdrum "Drawn" (1990), whose disconcerting and terrifying idea is taken for a sequence of "The cell" (2000), a film loaded with surrealist and colourful images that represent chaos and mystery of the human mind. In fact, this film includes other striking images inspired by contemporary works such as the series of animals preserved in formaldehyde by Damien Hirst.