STREET ART, POP SURREALISM, POST GRAFITI... FROM THE STREET TO THE GALLERY

Jan 8, 2018

art madrid

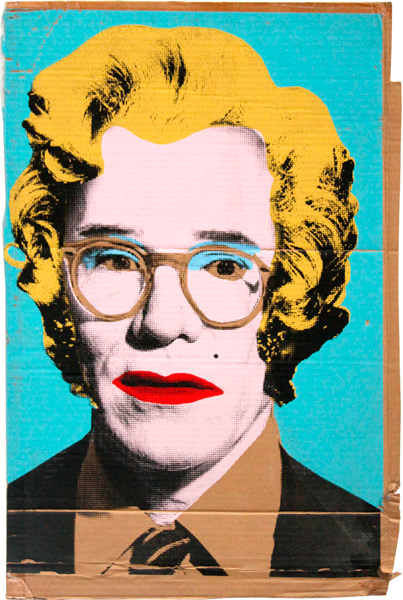

Mr. Brainwash, “Andy Warhol”, mixed technique on cardboard, 2016.

The street is a space of freedom, a territory of aesthetic creation and a channel of expression, on the other hand, the objects of consumption and the waste products of our hyperconnected society are tools of communication, protest, criticism, irony ... The Kreisler Gallery is a good example of this adaptation to new ways of doing art. Founded in Madrid in 1965, it opened spaces in New York (1970-1975), Barcelona (1979-2002) and Miami (1993-1995) to be aware of interesting movements in great art capitals and, today, with more than 50 years, it is a benchmark for its eclecticism, its rigor and its openness to contemporary street and urban art.

Kreisler has managed to make his story and his spectacular fund of consecrated artists (Miró, Tapies, Picasso, Joseph Beuys ...) live with the creations of the new artists. Okuda San Miguel is one of these new talents, an artist whose style was born in abandoned factories of Cantabria within the purest street art and is now absolutely recognizable worldwide and can be seen in the streets (and in the galleries) of all over the world. He says that he is a contemporary Renaissance admirer of El Bosco and that in his works (from murals of large dimensions to small embroidered pieces) he raises contradictions about the meaning of life and the conflict between modernity and our roots.

Spok Brillor, “K”, neon, 2017.

Spok Brillor is one of the most relevant figures of the graffiti scene in Spain. In the 90s he painted on trains and walls in Madrid where he acquired his own style with marked contours, brightness and light effects, saturated and vibrant color that maintains today in his pieces, urban atmospheres, almost psychedelic, in which mirages and surreal elements speak to us, among other things, about the influence of new technologies in art and the digital manipulation of images. He uses both figurative language and abstraction but always keeps the fantasy and humor as essential ingredients.

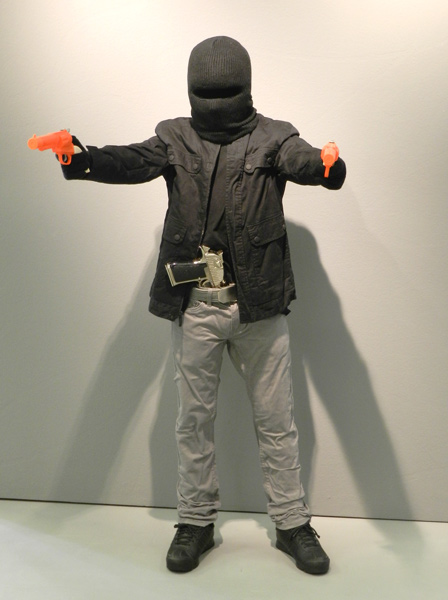

Mark Jenkins, “Boyz 2 Men”, mixed technique, 2017.

Another gallery that has incorporated the urban spirit into its fund is the Catalan 3Punts, putting into practice one of its founding principles that ensures that "art galleries are a dynamic element of the cultural scene of both our city and globally" and, as dynamisers, they must be up-to-date about emerging art and new trends. And they do it looking for excellence in any discipline. In this sense it must be enlighted the work of Alejandro Monge (Zaragoza), a sculptor by vocation but with a creative freedom that has led him to develop in a prodigious way the painting and drawing, that rubs hyperrealism, and that he mixes with graffiti, classical sculpture and pop art to result in pieces charged with social criticism. In alabaster, lacquered steel, porcelain, resins, in large canvases, his work is based on the contrast.

But if there is a graffiti artist famous for breaking the wall (and in a more than profitable way) between the streets and the galleries, he is the English Banksy, and if there is someone who received his blessings in the StreetArt circuit of Los Angeles that is Mr Brainwash (Thierry Guetta), star of the movie "Exit through the gift shop" - directed by Banksy himself and with footage of Guetta himself - and another one of the urban artists that brings the 3Punts gallery to Art Madrid. Thierry Guetta, of French origin, fell in love with street art through his cousin Space Invader and decided to film with his camera this cultural movement to which he ended up surrendered, already as an artist, supported by figures such as Shepard Fairey and protected by the commissions of the Hollywood jet set. According to him, his works, pure repetition and pop referents, "wash your brain".

Joaquín Lalanne, “Seguimos pintando”, oil on canvas, 2017.

Joaquín Lalanne (Argentina), in Art Madrid with the gallery Zielinsky (Barcelona), is also very influenced by pop and street art and he is ascribed to a surrealist style in which he links with Giorgio de Chirico and the Baroque, with a constant vindication: art as a space of freedom. With an almost Dalinian gaze and a lot of metaphysics, there are those who already speak of "Lalannism" and of Joaquín as a "young promise whose art is splendid and in which we must insist already" (Tomás Paredes, for La Vanguardia).

Paul Rousso, “Monopoly money composition”, mixed technique, 2017.

The gallery Hispánica (Madrid), for its part, offers us the great pop formats of Paul Rousso, an innovative American artist who creates volumes from a flat surface, what the artist calls "Flat Depth" and for which he uses complex artistic techniques as painting, printing, sculpture, digital manipulation and digital printing. Rousso takes pop culture and its contradictions and uses the act of discarding elements such as money, candy wrappers and magazine pages, then expand its size to unusual dimensions and create a metaphysical and ironic paradox.