GEOMETRICAL ORDER FOR A VISUAL ANARCHY: YTURRALDE AT THE CEART

Sep 5, 2019

exhibitions

The CEART of Fuenlabrada opens today the exhibition "Yturralde cosmos chaos (obras 1966-2019)" curated by Alfonso de la Torre, which can be visited until October 27th. Yturralde's long career has allowed him to travel through different artistic movements in a manner consistent with his creative impulses and artistic concerns, although never forgetting eclecticism and the fusion of techniques that have always characterised his work.

In his beginnings, focused on the study of geometric abstraction, Yturralde was part of the group “Before Art”. This collective, founded in Valencia at the end of the 60s proposed an approach to art devoid of any subjectivity or feeling. Their proposals resulted in works of scientific basis, with a claim of objectivity, in which there was little room for the artist's interpretations. What is there before art, as an absolute approach? This group had an unquestionable impact within the development of geometric abstraction in our country, following the trail of this movement initiated worldwide during the interwar period.

These first steps left a mark on Yturralde's work. As it happened to Sempere or Sobrino, also members of the group, geometry has been present in one way or another in his work, opening later to kinetic art with his series of "Impossible Figures." His entry into the Calculation Center of the Madrid University in '68 marks the beginning of his first computer work. This experience allows him to continue his exploration of forms with a methodology that is inspired by mathematical formulation and reveals the author's interest in optical games, chromatic distortion, volumes created by contrast and figures generated from pure geometry.

Another significant milestone in his career was his time as a researcher at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies under the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). In this period he began to experiment with laser light and refraction in faceted bodies, with a project entitled "Four-dimensional structures". The resulting works recover the aura of an abstraction based on recognisable rectilinear forms but add the mystery of the lights and shadows created by chance in unfathomable backgrounds of deep darkness. Yturralde experiments with new methods and techniques to further deepen the study of form.

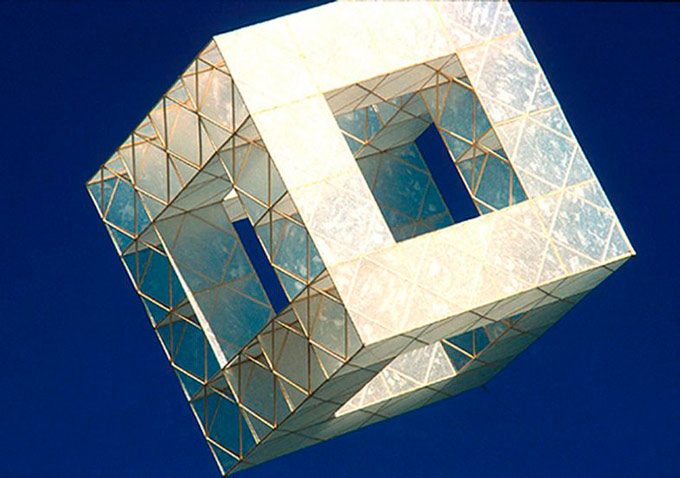

After returning from the United States, his work opens to happening, installations and performances. This creative line coexists with its constant interest in geometry, now approached from another dimension. The forms leave the plane and become three-dimensional figures that cross the blue skies. Thus the "Flying Structures" are born as guided kites from the ground. Polyhedral designs in white, red, yellow... are both a vital event and the result of a constructive test that defies physical laws. This exhibition will include several of these structures never seen before, which will receive the visitor suspended in the space.

From the 90s, Yturralde returns to the study of geometry and its relationship with colour. The "Preludes", "Interludes" and "Postludes" are presented as an analysis of chromatic varieties and the ability to generate volumes and contours with slight tone mutations. This painting is of enormous conceptual and formal purity and sometimes plays with that subtle tension between the framing and the unframing, the conscious search for a visual balance that forces the angles to the limit of bearable.

The exhibition is a tribute to this passionate of geometry that has dedicated his production to the study of simple forms and unfolded the high complexity that structures can hold. Besides, it will be the ideal opportunity to know the evolution of his work with a selection of more than 60 pieces, mostly large format, belonging to institutional and private collections that otherwise could not be visited.