Infinite Conversations

Jan 9, 2023

art madrid

Art Madrid'23 presents the section of interviews conducted by the art critic and curator Alfonso de la Torre in which he discovers, in greater depth, the artistic universe of the eight most outstanding creators of the following Art Madrid edition. The section, which presents the artists from private conversations and with its own content, will be included in a common theme around the figure of the artist and their practices in the national art market.

Starting on January 13, we will enjoy two weekly interviews that can be read in full on the Art Madrid website or viewed on video on the fair's Instagram channel.

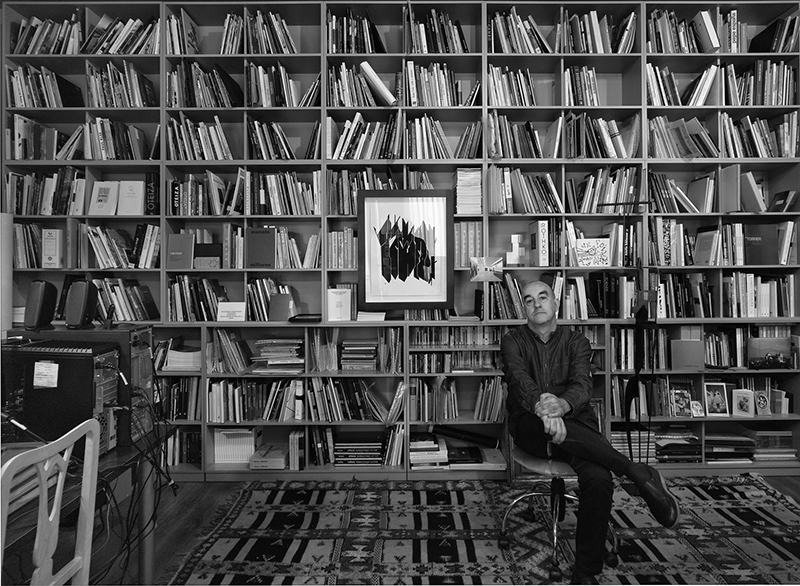

About Alfonso de la Torre:

Alfonso de la Torre (Madrid, 1960) theoretician and art critic. Specialist in contemporary Spanish art. He has curated more than a hundred exhibitions; He has published essays and poetry and taught courses at various universities and institutions: MNCARS, Museum of Teruel, University of the Andes, Menéndez y Pelayo International University, University of Córdoba, University of Granada, University of Castilla-La Mancha, UIMP, UNIA, Nebrija University or the University of La Sorbonne. He belongs to the International Association of Art Critics (AICA).

Perceval Graells, (Elche, 1983) (Alba Cabrera Gallery) seeks, through her works, to provoke a personal reflection in viewers about how we face the process of overcoming pain throughout our history; turning that pain into a space of peace and calm where we can recreate ourselves and reflect. In the work of Martínez Cánovas (Murcia, 1980) (Inéditad) we will find, through a surreal and symbolic imaginary, a direct connection with the philosophical thought of antiquity in philosophers who, like Aristotle, argued that death is the most terrible of all things and that fearing this and other truths is even fair and noble. The works of Cristina Gamón, (Valencia, 1987) (Shiras Galería) are distinguished by a visual freshness that the artist manages to achieve through a complex technique of unreal images, capable of transporting us to the oceanic abysses in which our mere presence is astonished before the magnitude of the color.

The works of Nicolás Lisardo (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1978) (Manuel Ojeda Gallery) aim to assess existential limits, adding a metaphysical tonality to those eroded facades of the city. It is an anti-picturesque scenario, which has the firm intention of moving us to the perception of the idea (eidos forme).

Isabela Puga's (Caracas, 1997) (BAT Alberto Cornejo Gallery) interest in architecture and urbanism make these disciplines a substantial part of her creative process, from which she drinks and adopts, especially her own geometric style. - pictorial. Starting from opposites: the shine of gold and the darkness of black, the artist questions and investigates essential elements such as depth, color, light, and space in her works. She intends to foster the relationship between subject-object and space. The paintings by Francisco Mayor Maestre, (Madrid, 1990) (Aurora Vigil-Escalera Gallery) flood the set with color, excessive vegetation, and impossible planes that break the figuration of the work. Outstanding in his conception of shared spatiality are curtains, awnings, laundry, and air conditioning units... In an investigation of the freedom of painting, the exploration of spaces, and the claim of individuality. The plastic works that Pedro Peña Gil (Jaén, 1978) (Metro Gallery) has carried out in recent years, constitute a return to the attitude of those explorers who wanted to extract the light qualities. Although, in his case, adding the element that best presents him: color. The experimentation of these works, like the first photographers, leads him to take the images of the world as a metaphor for the anonymous Petri dishes. Mario Soria (Barcelona, 1966) (Gallery N2) is a profound connoisseur of the western pictorial tradition and its techniques, and he uses them to subvert them with his particular sense of humor. His works mix American pop art and the European tradition he calls “interstellar pop surrealism.”