THE EXISTENTIALIST FAUNA OF DANIEL SUEIRAS

Jul 17, 2018

art madrid

Daniel Sueiras feels an undeniable concern to comprehend the human being as a whole, to understand essentially the cause of ourselves, the reason of our society and the meaning of the beyond, the when and where of our (apparently) random existence. The transformation of this universe of thoughts in his work takes various forms. His versatility as a painter and sculptor translates into a catalogue of characters that play with humour and irony to offer a different reading of life. It is a permanent questioning of the status quo that Daniel masters and finds an outlet in one of his most ambitious projects "Natural selection". A compendium of ideas embodied in formal portraits, classic poses and old clothes that question the viewer. Today we are lucky to interview this artist and learn about his creative proposal.

In your work, it seems that animals are better off than people. The use of irony is undeniable. How do you leap in your work to the pictorial fauna of the "Natural Selection" project?

The “Natural Selection” project arises mainly for two reasons. One is purely practical and the other theoretical in content and meaning.

Since I started painting, all the series I have worked on have had a clear existentialist character, where everything dealt with the universal questions of who we are, where we are going and where we come from (something not too original today, I have to admit). In my previous series, I intended to represent man as an animal that is torn between his instincts and his reasoning, which projects into the natural world in the form of physical creations. That is why sometimes I made "portraits" of washing machines, butane bottles, cabinets... for me they are not just objects but materialisations of mental processes... a sort of human entities.

Over the years, the conclusion became increasingly evident: we are animals that have adapted very well to the environment thanks to our intellect, but in the same way that other beings have adapted to the environment. I discovered that this thought does not have as many followers and most humans have difficulty assuming that we are animals, and often we see the natural world and the rest of living species as something tremendously alien and, what is worse, often as something inferior.

That is part of the underlying idea of “Natural Selection”, which in turn is a tribute and an irony to and about Darwin's revolutionary discoveries. An irony, since it has been the human being the only one capable of unravelling the mechanisms of life and who refuses to believe such discoveries. And an irony too, since it is deduced from Darwin's discoveries that evolution occurs because they are the species best adapted to the environment the ones that survive and have offspring, while our species, the humans, has long been pretending that it is the medium who adapts our needs.

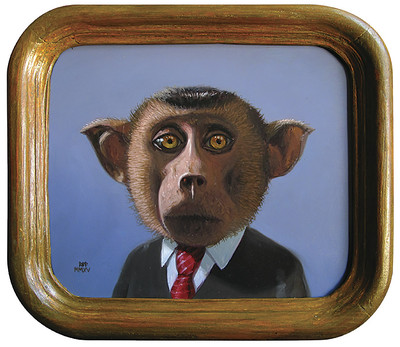

What has always interested me is portraying people in ways that make their animal nature visible, but above all, I love the portrait and the psychology that transcends from it. Some people buy a portrait of an animal because it is funny or tender, others are aware that behind the tender or ironic envelope there is a deeper meaning... for me, the important thing is that the work is there, with multiple readings maybe, but with a clear intentionality too. I must admit that today this series has some tragicomedy not only in its aesthetics and content but also in its own gestation process.

Your portraits elevate your models to the human category. They tend to be posed and formal images. What is the psychology of these characters? Is it the humanisation of the animal or the dehumanisation of the individual?

The question is so accurate that it is the answer itself. Indeed, I raise the rest of animals to the human category (since such a thing does not exist, it is like almost everything, an invention of ours). And I do it as an irony to that supposed differentiation of rank. In the same way, I humanise the rest of the animals, to show that our standards and concepts are all, as I say, our inventions: beings that define themselves as superior and special. I also try, unlike some painters of the past, not to make hybrids of humans and animals: heads of animals on human bodies... I'm not interested in that, if I paint a large portrait of a mouse, maybe it will be dressed, but the suit covers its mouse body. It’s a mouse.

In the process of creating a new work, what leads you to opt for painting or sculpture? What influences do you have in the choice of composition and style?

The development of an artistic idea is always difficult to explain since I believe that many factors influence. As for the choice of medium, painting or sculpture... I would say it's like when you put on some trousers; you already have the trousers on, now you have to look for a better outfit that matches them. Often, the idea or concept itself already requires a medium; it is about adapting the idea to the form and finding out which one best expresses its content.

The question is frankly interesting and if I had to choose a feature of my characteristic work would be that, the composition, even beyond the style. Unfortunately, often one does not realise the relevance of the composition in the effect produced in the viewer when observing the work.

I have always been interested in psychology in art and the effect it produces on the viewer. I am interested in a painting that has no escape, that looks at you almost before you look at it. There the composition comes into play. My images are usually very strong, frontal poses, profiles, foreshortenings at most... always very rigid. The look of everything depicted always goes outwards, looking for the viewer. I almost never represent action, if there is action everyone already knows what is happening, if there is not, it becomes more psychological, more disturbing...

The background also counts. They are usually empty or with patterns so that all the attention remains on the portrait, just as I understand that the frame must enhance the painting. In fact, in this series, I consider the frames a part of the final work, with the same importance than what is painted, as they reinforce the set of the idea and irony.

So yes, the influences before or after my work would be above all, Egyptian art, Sumerian, Assyrian, early African art... all art rigid in terms of form, in terms of expressiveness, but deeply psychological and disturbing, precisely for that reason of lack of movement.

My thinking about style is relatively basic, in these works I am quite realistic. I am interested in the first impact of the work comes for what it represents, not for how it is executed... in that sense the closest to reality, the fewer it conditions the effect I seek in the works of Natural Selection.

This line of work is an open project that you combine with other works, such as personal portraits, do you have in mind any other artistic challenge?

Yes, I have been working for several years now in another series: Africa. In it, human beings reappear, and although I have not found enough time to work on it, I already have even thought of future series beyond it. Fortunately, ideas are not lacking; time is what is most difficult to find to carry out so many projects.

You have a long artistic career that has developed both inside and outside our country. In your experience as a creator, who has differences in the way of approaching art in other countries concerning Spain?

I would lie if I denied that there is not some of that. I live in southern Spain, and in our own country, there are differences as one travels up along our geography. In the same way, I would dare to say that something similar happens as one leaves Spain towards other countries.

I think it has to do with culture, with climate (which in turn has to do with culture). Where I live, living in a certain way is considered an art, so the one who makes art is seen in some way a “bon vivant”. Here, there is incredible creativity, and perhaps that is why it is valued little, in some way, the irony, the originality, the creativity are quite common, and that someone, besides, can make out of it his way of life might even cause astonishment.

Maybe we should change aspects of our culture... but I'm also afraid of doing so. It is difficult to change some aspects without changing others. I think I have a frustrated vocation as an anthropologist and I often try to understand the mechanisms of cultural and environmental processes, and often understanding reality makes it very difficult to judge.

Here, many people have to emigrate although they would like to stay since there is little work and often their skills are not valued and/or required. I feel privileged to be able to live here, even if it's thanks to exhibiting in other places.