NH Gallery in Art Madrid\'15

Feb 11, 2015

art madrid

|

|

La telaraña mágica. Álvaro Barrios.

Nohra Haime Gallery has just turned four years of life in january. This young gallery, established in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, has sought from the beginning promoting artists from all backgrounds, not just Colombians, showing a broad spectrum of contemporary art with works from all artistic disciplines. Nohra Haime also has headquarters in New York. Both locations are focused on designing a strategy for cultural exchange in the north-south axis of the American continent. Furthermore, the gallery has sought to effectively promote their artists through collaborations with other cultural institutions and the art world, which have become monographic exhibitions at venues such as the Art Museum of the Americas, Training Center Spanish Cooperation in Cartagena and the Museum of Modern Art in Barranquilla.

|

|

|

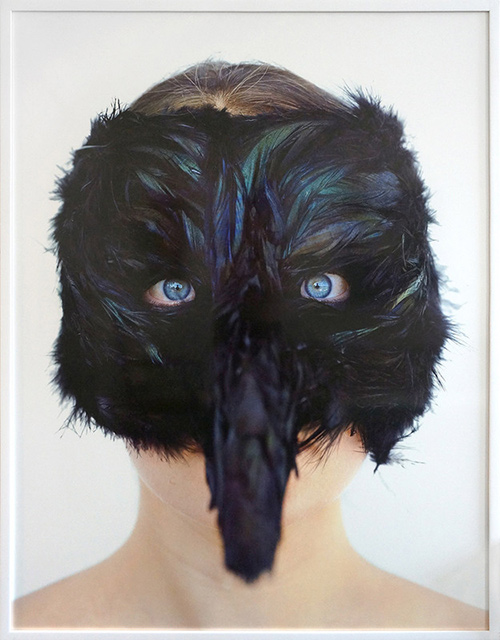

Prey. Natalia Arias.

The director of the gallery, Sara Angel, brings to Art Madrid'15 a proposal in which highlights the art made by women with works of Niki de Saint Phalle, Alvaro Barrios, Julie Hedrick, Valerie Hird, Ruby Rumie, Natalia Arias and Francisca Sutil.

|

|

|

Les trois graces. Niki de Saint Phalle.

Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2000) is one of the most influential creators of the second half of the twentieth century .

This Franco-American artist received an education in line with the social codes of New York's upper class. However, his unique worldview, their rebellion and creativity joined to not follow the script was already written for her. Niki de Saint Phalle is a self-taught artist who has been defined as a feminist, radical and political.

In Paris at the New Realists is linked in the 1960s, when his series of her shooting paintings , and since then uses the media, like Andy Warhol, to consolidate their public image. His career includes numerous public art projects, among which are The Tarot Garden in Tuscany, or The source Stravinsky in Paris. It also conducts experimental film and stage designs for ballet but, above all, reach the public with the development of their Nanas, huge sculptures that revolutionize the representation of women in art.

|

|

|

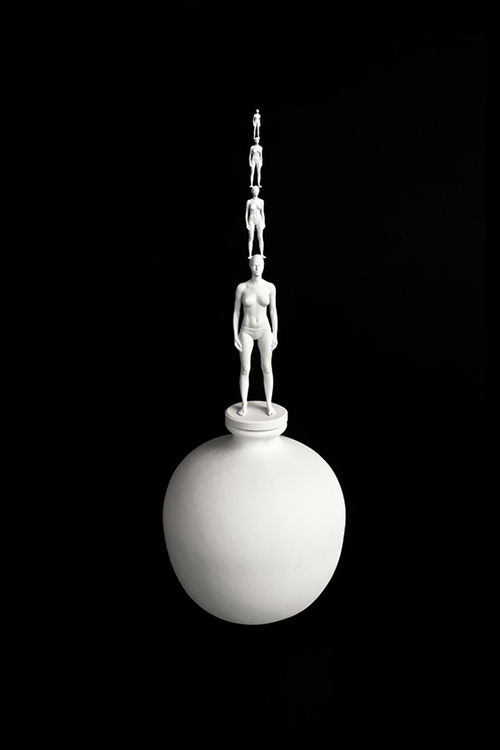

Vasija coronada. Ruby Rumié.

Born in Cartagena de Indias (1958), Ruby Rumié studied in the Fine Arts School of Cartagena de Indias. Since her first exhibition (1985) in Cartagena, in which she was clearly influenced by the hyper-realism, Ruby has tried to reflect the face of characters belonging to the Cartagenian landscape, being then the coachmen, musicians, barbers, children, women, old men and black nobles, the protagonists of detailedly made portraits. The assembly with dolls and geometrical accessories has been another period through which Ruby's artistic life has passed, who was also interested in acrylic technique, as the outstanding characteristic in some of her creations. We can talk about an evolution in which Ruby has taken as departure point the classic to reach to alternative presentations in which she achieves to involve painting, photography and other techniques to show her change of perspective. She has made important exhibitions in: Bogotá, Barranquilla, Cartagena; Santiago de Chile; Miami; Nueva York; Washington; Rouen; París. Rumie participated recently in the international section of the First Contemporary Art Bienal of Cartagena de Indias. She actually lives and works between Cartagena in Colombia and Santiago de Chile. |