PERFORMANCE AND SOUND IN THE LAST ART MADRID'S EDITION

Apr 15, 2020

art madrid

When it comes to exploring new artistic disciplines, it is sometimes difficult to define what the present and the future hold for us. The concept of "contemporary art" itself has shifted in time from the present moment to encompass not only the most immediate but also what was created twenty years ago. Thus, what we call contemporary today will no longer be so two decades later, as it happened to the art of the 70s or 80s, then also known as such. Before a mobile and fickle adjective like this, the efforts of definition, so typical of the still-acknowledged academicism, of the innate need of a man in society to understand his context, of the tendency to consolidate the profession by sealing terms that are habitual and understandable, they are somewhat unsuccessful. Reality offers us a panorama that has learned to avoid labels, that responds to a seasoned and irrepressible creative impulse for which inherited notions are not worth.

In this context, Art Madrid has wanted to organise in its last edition a program to accommodate hybrid expressions that are committed to new-generation art, where the boundaries of concept and shape are already overcome. This program aimed to transform each action into an experience for the spectator, in an experience that overcame the most contemplative barrier of art to open a direct dialogue with the observer. One of the highlights of the program was the performances that took place during the fair itself, with a variety of proposals that broaden the understanding of this term and take us into an unrepeatable creative reality, which can only occur at that time and place.

For all those who have not been able to attend or even for those who want to remember, we bring you a reminder of two of those performances, in which one of the basic elements was sound and synchronisation with the image. We refer to the performance "RRAND 0-82" by Iván Puñal, which took place on Wednesday 26th, and that of Arturo Moya and Ruth Abellán, "Barrel of the Danaïdes", on Friday 28th of February, during the fair Art Madrid’20.

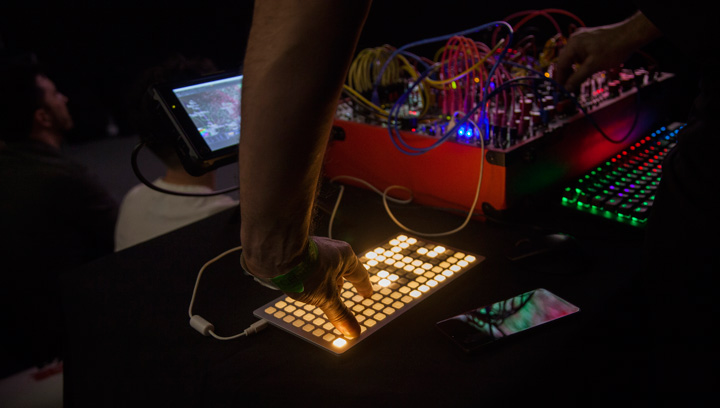

Iván Puñal's proposal is a unique and unrepeatable work, based on the author's interaction with the screened images and the creation of live music. For this reason, each staging of “RRAND 0-82” generates a new piece, made from scratch to open a dialogue between image and sound.

This project is based on a simple approach: is there true freedom? To what extent are our acts predefined by factors that we do not choose? Where does the true consciousness, the control of the "I" begin? The questioning of our decision-making capacity, the apparent illusion generated in ourselves that we freely choose our fate and the course of our lives, contrasts with the fact that many elements are given to us (environment, social situation, place of birth, genetics, etc.), and even neuroscientists claim that the vast majority of our brain activity is unconscious. That being the case, what does the concept of freedom respond to, is it an empty term?

On these premises, Iván Puñal presents a live intervention in which he tries to explore the edges of human decision and his ability to respond to unpredictable situations. To do this, based on a set of images generated by a non-predictive algorithm, the artist sets out to create sounds that accompany them and at the same time modify the behaviour of the mathematical formula so that it continues its process of visual elaboration. In this way, the mechanism feeds on itself and human intervention tries to be as little controlled, predictable and conditioned as possible. The result is a unique audiovisual work, created at the very moment with a wrapping and captivating staging that also plays to offer us an approximate representation of randomness and free will.

Of a different nature is the performance by Arturo Moya y Ruth Abellán. The title "Barrel of the Danaïdes" refers a mythological account in which 49 of the 50 daughters of Danaus are sentenced to eternally fill a bottomless barrel with water after having murdered their husbands on the wedding night by order of their father. Danaus' daughters married the 50 sons of his brother Egypt, as a sign of reconciliation after long enmity, but it was all a trick to eliminate the possible descendants of Egypt and annihilate its power. Of all the daughters, only the eldest, Hypermnestra, saved her husband's life.

This story is often taken as a reference to represent the dichotomy between obedience to parents and the performance of a prohibited act, because in the classic narrative, Zeus initially punishes Hypermnestra for disobedience, although later, during the Avernus' judgment, she is acquitted while the other 49 sisters are sentenced. Likewise, this story takes up the idea of repetition, eternity and fluidity, through the water that the Danaïds must constantly pour into the barrel, in an infinite action that does not release their frustration.

The performance by Arturo Moya and Ruth Abellán is inspired by this mythological narration to take the constant flow of water as a visual starting point for a sound action that both star in front of the public. The performers sing one into the other's mouth, enclosing the sound they emanate and representing the impossibility of propagating out, in a cyclical and hypnotic action that synchronises with the images screened behind them.

In the screen, we see the two performers drenched in water, water whose flow becomes denser or weaker in response to the sound they make when singing live. But there is no barrel to fill, the water does not stop falling, the voice never comes out... And everything is part of a live-action where, above all, the enormous intensity of the looks, the rapport of two interpreters who respond to an impulse fed from intimacy and reserve, who sings one inside the other when they feel that they must do so when looking at each other, and who metaphorically immerse themselves in a watery and translucent space that moves and overwhelms us.