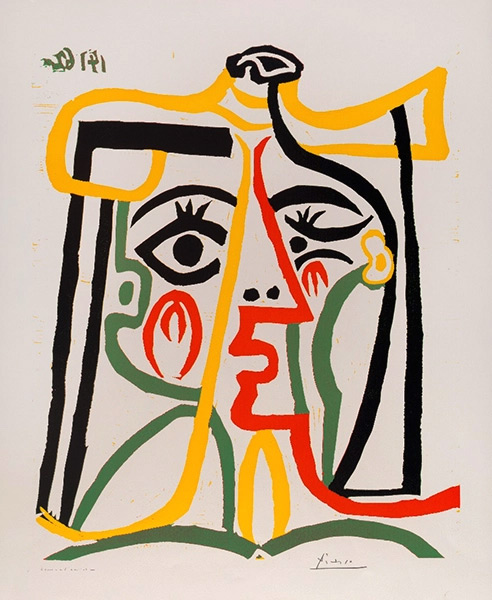

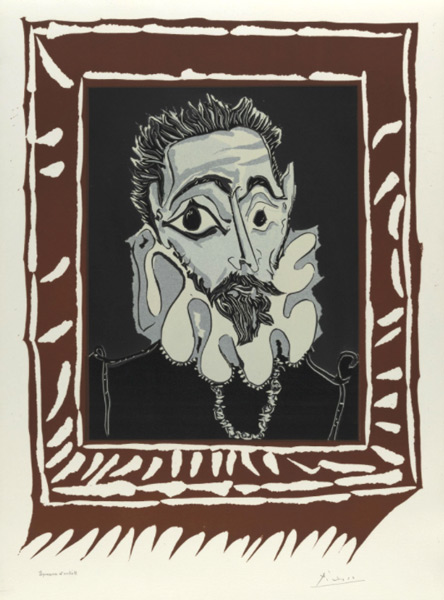

PICASSO AND THE MASTERS

May 2, 2018

exhibitions

In every training process, artists learn from the masters; they copy the techniques, styles and works of their predecessors until they mature their own creative personality. This evolution necessarily involves imitating, repeating and interpreting the most representative pieces of art history as references. From there, the particular identity of the artist builds up, which is sometimes supported by previous works to offer an updated reading. This has happened with Duchamp, Modigliani, Damien Hirst, Goya, Bacon ... and Picasso himself.

Picasso used to say that "great artists copy, geniuses steal". This master of the 20th century also wanted to reinterpret some of the most iconic works of the history of painting and to do so he has sought inspiration in major European museums, such as the Prado or the Louvre. With his work, the author from Malaga adapted to the new times of modernism based on the classics.

The Círculo de Bellas Artes hosts the exhibition "Picasso and the Museum" in which it explores this facet so little studied by the painter. Much has been written about the origin of Cubism and the imprint of Picasso in the universal history of painting, however, his work has not always been analysed from the perspective of his great influences.

Since Picasso visited the Prado when he was 13 years old, the impact of these great works, which so much impressed him, can be traced in many of his compositions. Ingres, Manet, Velázquez, Courbet, Zurbarán, Delacroix, Rembrandt ... have left a mark, not always evident, in the author's imagination. Sometimes hidden among the angles of his cubic figures or hidden among the strokes of his sketches ... the inspiration has a lot of homage and imitation.

The exhibition is open until May 16th and completes with a program of guided tours and children's activities designed to understand better this unexplored aspect of Picasso’s work.