THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD IN A CHALLENGE FOR PRESERVATION

Sep 2, 2018

Breaking News

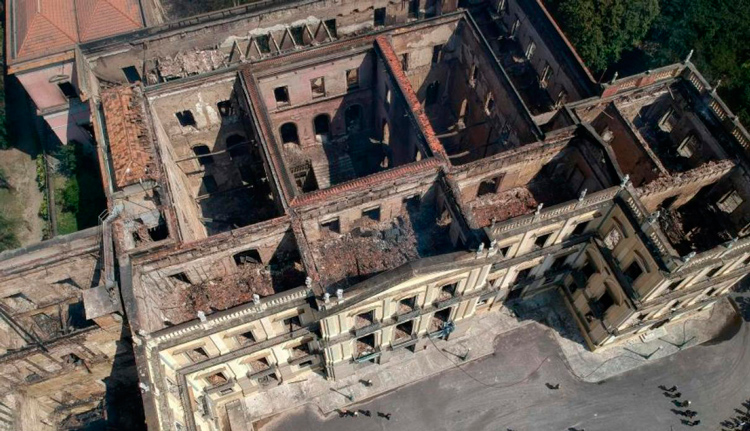

The catastrophe for the loss of the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro by a devastating fire last Sunday reopens the debate on the investment of resources in the maintenance of these institutions. This museum had 200 years of history, housed the largest collection of natural history and anthropology in South America and was the fifth gallery in the world for its funds, with a collection that exceeded 20 million pieces. Only the huge 5-ton meteorite has survived. Unfortunately, the centre's employees had been demanding for years more resources for conservation and maintenance, drastically reduced in 2014. On the night of the fire, only four guards watched the building. Something insufficient to put the fire under control or ask for help more in advance.

This tragedy questions why the budget for culture is the first to suffer cuts when a country must adjust to the current economic situation. And at the same time, it also raises a question of responsibility on how the maintenance of all these collections can be sustainable in the long term, something that is increasingly costly. Numerous authors and analysts say that reducing investment is more harmful than beneficial, because it restricts the options for attracting new funds, limits the scope and involvement of citizens, and, above all, decreases the dissemination and enhancement of collections.

Another recent case that raises questions about good management is the deterioration of the collection of the Royal Academy of San Fernando. The institution has been complaining for two years about the demolition and construction works of the Canalejas complex, located on the opposite sidewalk, which have damaged its aeration system and have introduced a huge amount of suspended dust that is now dropping on the paintings and sculptures of its rooms. The academy has closed to the public several rooms, waiting to restore the artworks and to ensure their conservation. Some critical voices point to the fact that the works undertaken in the area did not include an adequate plan on the consequences of the demolition, and that at the first signs of damage, the impact and the action-measures should have been re-evaluated.

Likewise, it is striking that being Spain a country with such protectionist regulations of our cultural heritage, some actions, often irreversible, that involve a direct attack against the maintenance of goods, are allowed. The Canalejas complex that we mentioned above is today an empty shell of what was a group of historic buildings in this central block of the city. From a bird's eye view, we can only see the façades standing. The project, after several missteps, standstills, and administrative requalifications to eliminate the status of "protected" property, seemed to obey more economic-urbanistic criteria than the conservation of heritage.

Let's take all these examples as a lesson in life from which to draw good teaching. We make culture among everything and it is for everyone, beyond ourselves.