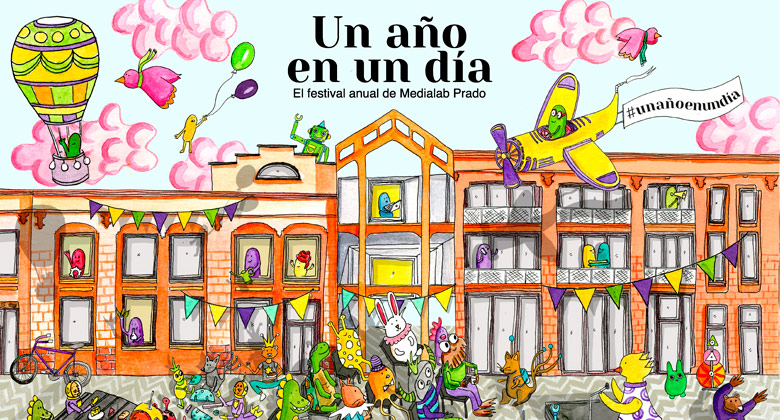

HERE IT COMES THE GREAT PARTY OF THE YEAR OF MEDIALAB PRADO

Dec 5, 2019

calendar

MediaLab Prado faces like every December a difficult challenge: to summarise in a day the work of a whole year and share it with the citizens. With this premise, the essential date on the agenda is approaching. The 14th you can not miss “One day in a year. Annual MediaLab Prado Festival ”. With an intense and varied program of activities, the centre opens its doors to families, curious and neighbours with the purpose of turning this pre-Christmas event into an encounter of exchange, knowledge and entertainment designed for everyone: from 0 to 99 years.

For the little ones, MediaLab Prado has created a special program to stimulate all the senses. Starting with music storytellers, followed by Japanese percussion classes, going through performances that recover the poems of García Lorca, Alberti or Gloria Strong. And that's not all, because there will also be room for fantasy and imagination in activities that involve body and mind. Some of these workshops are run by Blanca Helga, a children's illustrator specialising in play-books for children that she edits in the publishing house "Hopitihop" founded by herself. With Blanca, kids can create fantastic characters from cut-outs and collages, as well as start their first artist book with digital tools. And paying attention to body expression, there will also be an experimentation workshop on the body and the way we understand it, by the hand of Giz&Gif.

The connection between art and technology will be available to visitors with an immersive virtual reality experience throughout most of the day. This proposal is in charge of the Synthetic Realities Laboratory (LabRS), one of the centre’s workgroups that investigates the development of these virtual environments. On the other hand, there will be a presentation of all the projects carried out throughout the year, among which we highlight "Dark Light", the result of collaboration with Debajo del Sombrero, BIVO and "Autofabricantes". The first one will show the result of the residences carried out in the centre by autistic artists selected by the association Debajo del Sombrero throughout 2019, with projects arising from naturalness and spontaneity without conditioning. For its part, BIVO is an initiative that seeks to raise awareness about the need for responsible energy consumption, while investigating the manufacture of prototypes that allow the generation of energy through human movement. “Autofabricantes” is a space to investigate the technological advances applied to the elaboration of prostheses through open source, in addition to maintaining a community of exchange and support between participants and families, under the guidance and contribution of the “Exando una mano” group.

And you could not miss the use of the square. In addition to breakfast with some ‘roscon’ and hot chocolate as the first thing to open the day, from 6 p.m. the LED facade will be available to visitors, first with an interactive game of ping pong, and then a sample of the projects created for this device throughout the year by institutes, universities and academies.

This is just a preview of everything to enjoy the following Saturday in a meeting designed for everyone to participate. We invite you to consult the rest of the programming HERE and make a place on the agenda for this essential appointment.