THREADS, NEEDLES AND FABRICS IN THE WORK OF 4 WOMEN ARTISTS

Apr 8, 2019

Breaking News

It is not the first time that we talk about the use of alternative plastic techniques to let imagination and creativity run. This is the case with threads and embroidery, which transform on this occasion into a refined form of artistic production far from its immediate use in the world of sewing. All these pieces require infinite patience and give an example of tenacity, of love for things well done, of dedication, devotion and the search for new narrative discourses that deviate from expected in the field of visual arts.

Undoubtedly, sewing is a task linked to women since time immemorial. A quick search in any compendium of art history throws many works in which women appear sewing, most of the time by hand, in customary scenes. These images compose an imaginary fueled by ideas such as care, attention, dedication, until they become concepts almost inseparable of femininity. Today, many women artists (because that is still the case, the female creators are the ones who opt for these techniques) use these resources with an intentional value, to allow re-readings on this type of work and give a second life to threads and needles beyond the servilism traditionally associated with these domestic tasks. At the same time, some people do an exercise of abstraction to build a more subtle message and contribute to the empowerment of women by showing the potential of these techniques in the field of artistic creation or by hiding a story that demands attention in the visitor, invaded by an infinity of visual proposals.

Louise Bourgeois started sculpting spiders as a tribute to her mother, to whom she was very close. She ran a workshop for sewing and repairing tapestries, a reconstruction work in which Bourgeois began when she was barely 12 years old. This figure represents the working and dedicated personality of her mother, because spiders can re-weave their own net, to build threads that reinforce it, to overcome adversity and continue their meticulous work with transparent silk.

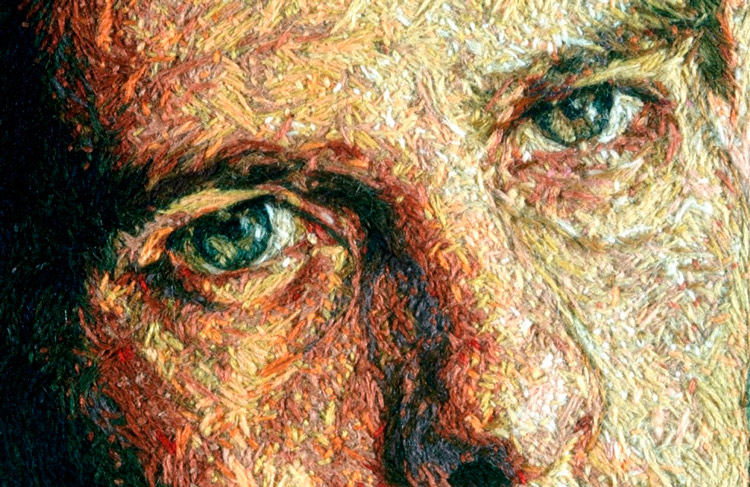

Although Louise Bourgeois opted for sculpture, numerous artists pick up the sewing materials to create their works. In an exercise of skill and artifice, Cayce Zavaglia (Indiana, 1971) is able to create these incredible portraits using canvas and coloured wool threads. The result is a work that simulates the small touches of a brush on a neutral fabric, to give all the depth, volume and texture of a real painting. With constant colour transitions and changes of direction in the stitches, her pieces are proof of the expressive capacity of these materials, with surprising versatility.

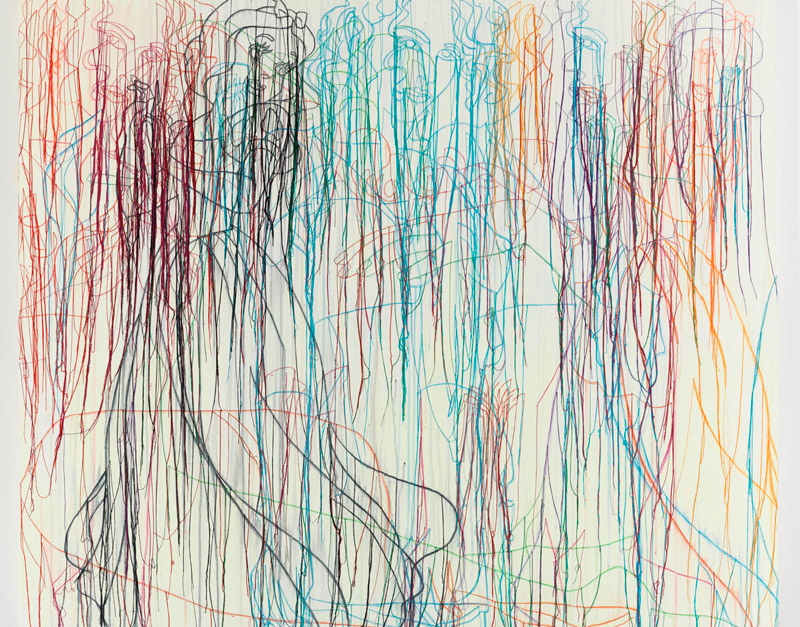

In other cases, the use of the needle and thimble seeks to convey a message that transcends and breaks the moulds established on social roles and the tasks entrusted to each gender. The artist Ghada Amer (El Cairo, 1963) decided to close a personal wound caused by her experience when she was rejected in a painting course in which the teacher only selected men, with a work that ridicules the vision that the male gender has spread about women. She found her inspiration in the stereotyped female representation he found in erotic and fashion magazines and animated children's films. The result is a work embroidered with coloured threads in a reinterpretation of pop art transformed on canvas that excludes the man from the scene and shows women-shapes responsible for their own pleasure.

In another way, the work of Raquel Rodrigo (Valencia, 1985) is developed through her project "Arquicostura". Her purpose is to embroider the walls of stores with cross-stitch compositions and make everyday life more beautiful for everyone. She has interventions in Valencia, Fanzara (Castellón), Salamanca, Zaragoza, Buñol (Valencia), Madrid, Bristol, London, Milan and Qatar. It is also a way to rescue domestic art that all women used to decorate their homes. Taking it to the streets and offering the world this job means putting it into value and appreciating it for what it really is.

Finally, we highlight the work of the Japanese artist Kumi Yamashita (Takasaki, 1968), who makes amazing portraits with a hybrid technique that intertwines a monochrome thread on a plot of nails to create the shapes, shadows and depth of the faces portraited. Although this is not the only discipline that she works at, the impact of these works has earned her broad recognition worldwide.