WHAT DO ARTISTS' STUDIOS HIDE?

Nov 21, 2019

Breaking News

Visiting an artist's studio means entering an intimate field and breathing the creative environment that surrounds the author's work. When one enters this space, all senses are on to trace and locate those little details that tell us a little more about the spirit and thought of the artist, the corrected sketches, the rectifications, the essays, the tests pinned on the walls, the traces in reused paper, the notes, the newly sharpened pencils, the stains of paint... We speak of orderly chaos, of a sphere where work and inspiration coexist and that the creators resist sharing, because, sometimes, opening the doors of the studio is almost like opening the doors of the soul.

These spaces also have a halo of mystery, intimacy and familiarity in which we must move forward cautiously, being careful not to go too deep, to discover the secrets as far as the artist wants to confess. But it is also the ideal opportunity to enter into direct communication with the work, to know the production process from its beginnings to the end, to understand the doubts, the intentions, the aim and the message of a project from the bowels.

In the past editions of Art Madrid, we were lucky to visit Rubén Martín de Lucas's and Okuda San Miguel's studios, guest artists in 2019 and 2018 respectively. With Martín de Lucas we were able to know in detail his great vital creative project “Stupid borders”, from which different concrete actions with their titles derive. Still, all of them respond to the same idea: deepen in the relationship of man with the earth and understand the artificial patterns that we impose as a society. In the studio, we could see his most recent pieces and understand the process of conception and expression, the reasons for choosing one discipline or another, his latest video works and the millions of notes and sketches of each line of the project.

Okuda San Miguel opened for us the doors of his studio in 2018. This large diaphanous white-painted unit looked like the perfect canvas for its multicoloured pieces, in the middle of shelves and tables full of spray cans. At the time of the visit, the artist was giving the final touches on the work "Lake of Desire" of 6x3 m, which he made exclusively for Art Madrid and could be seen at the entrance of the fair. This painting is inspired by the Garden of Earthly Delights by El Bosco, an author of reference for Okuda and that continues to arouse the interest, surprise and curiosity of many. The large format pieces coexist with small-sized enamels, in addition to sculptures, test boards and huge sketches for buildings' facades. Because Okuda works big and has a complete team that helps him focus on his work. As he explains, the creative process never stops, and having a team allows him to carry out so many projects at once.

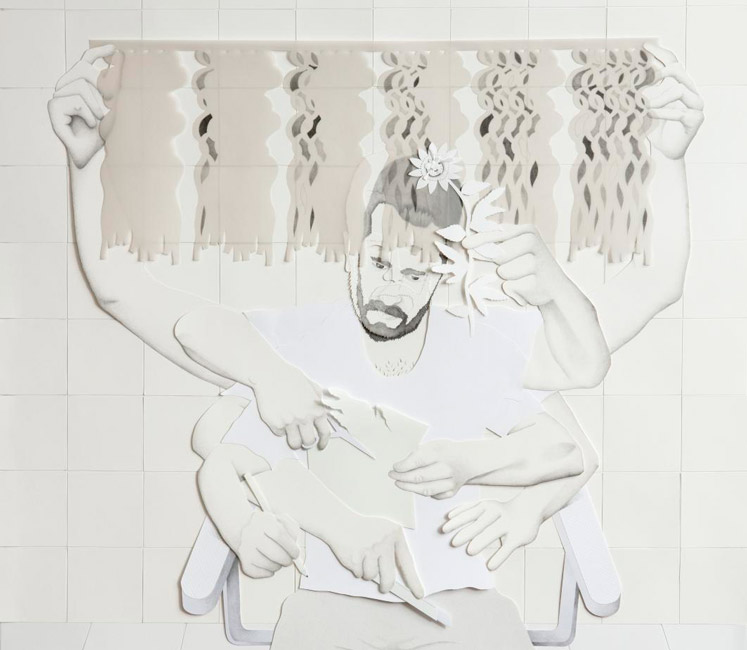

Some other artists make their own home their studio. This is the case of Guillermo Peñalver, to whom the ABC Museum of Illustration dedicated an exhibition within its program "Connections" with the title "Self-portrait inside." His voracity for the cropping, the use of paper in various shades, the overlapping of whites and the discreet use of the pencil make Peñalver's work a delicate and intimate one, like the scenes he recreates. In this case, the vision of his collages is like a visit to their house/studio, where the rooms become multipurpose spaces, and the daily actions take the stage. The last work of this author is a sincere exercise where he represents his day to day from the precarious reality of the creator that fuses his work with his daily activity.

Honouring this direct relationship with the author that occurs when visiting the studio, David Heras launched his project FAC (Home Art Fair), which counts already on five editions. The idea is to foster an open dialogue with the creators by exhibiting their works in a domestic environment and eliminating traditional market barriers. Although the initiative continued to grow, the original proposal was born in David's own house, who opened his studio and his home to exchange, knowledge and experience. It is about linking to art from personal experience, meeting the artists and enjoying their work, whether in the kitchen, the living room or the bedroom.