WHY SHOULD WE EDUCATE IN ART AND CULTURE?

Jun 5, 2019

Breaking News

Even today, finishing the second decade of the 21st century, the need to educate in art and culture is still an open topic of debate. It is commonly thought that the culture, to whose creation we all contribute, arises by spontaneous generation and does not need maintenance or attention. But on the contrary, culture as a social phenomenon, and art, as one of its particular tangible manifestations, requires the contribution of all. It only takes true meaning when there is a conscious exchange between the historical and identity legacy that culture transmits and the new uses and meanings of value that modern societies attribute to it. Well understood, culture does not need many resources to develop, since, as a social phenomenon, it will emerge and grow wherever there are individuals. But what it is necessary to do is "educate" in the importance and value that culture has per se, because without this educational work there is a destruction of the past, a depreciation of the heritage created over centuries and a loss of the close referents which give meaning to our contemporary society.

Far from what one might think, educating in art and culture is much more than learning history and artistic techniques. Art is an expression that emerges in a specific context, and, as such, transmits a large part of the elements that determine the culture of that particular time and place. It would be difficult to think that the Renaissance creators reflected in their works the concern for climate change, as they now do, or that the new authors capture with the same zeal religious scenes that were the favourite leitmotiv of the painting of yore. For this reason, to accommodate art and culture in the classroom is to channel a collective knowledge developed over the centuries that constitutes the best vestiges of our identity as individuals belonging to a particular context.

Unesco has pointed out that the mastery of culture and the arts is fundamental for the development of people. For this same reason, it encourages designing educational programs that incorporate these branches of knowledge. The benefits are diverse: education in art fosters alternative thinking and the search for creative solutions to problems, favours qualities such as tolerance and sensitivity, helps diversity to be appreciated and to open an intercultural dialogue, as well as developing other intellectual and creative abilities of the individual.

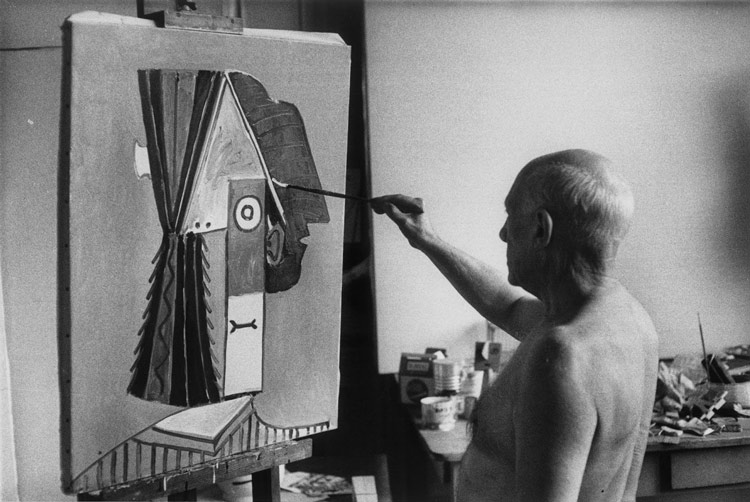

«Each child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we have grown up»

Pablo Picasso

Why is art still seen as something reserved for a few? In the same way that other disciplines equally necessary for development, such as sports activities, associated with collaborative values and psychomotricity, art and culture, require the same attention. In recent years, several voices have highlighted the benefits associated with training in art from early ages. More than a matter of convenience, it is, in reality, an essential content for the development that will go along the individual in different stages of life. Concepts so demanded in the modern business world as creativity, imagination or innovation, are based on stimuli taught from childhood. Nowadays, intelligence and the use of qualities are not limited exclusively to being proficient with language and mathematics. The promotion of alternative thinking and the solution of ingenious problems, with their well-known applications in the world of entrepreneurship, are intimately associated with art training.

Several studies suggest a change of approach when incorporating arts into education. The benefits are innumerable and alter the preconceived and inherited schemes even today on the permanent search for accuracy in the results, typical of subjects such as mathematics. The unpredictable essence of artistic creation helps to develop critical thinking and generate alternative ways of reasoning. The ideas of right and wrong are blurred, and there is room for means of expression that favour new structures of logical discourse. There is no single form of intelligence, and it is clear that the integration of art and culture in the learning process is necessary. Hopefully, this gradual awareness will translate into the incorporation of new tools and educational resources from childhood. It is only possible to love and understand what is known.