FEMALE ARTISTS THAT DO NOT APPEAR IN HISTORY BOOKS

Nov 30, 2017

calendar

Sofonisba Anguissola, “Bernardino Campi painting Sofonisba Anguissola”, circa 1559.

In the attempt to bring to light the female figures that have stood out throughout the history of art certain names spring up in a recurrent manner, such as Sofonisba Anguissola, a Renaissance painter who achieved a great reputation in life. This example, however, is that of a privileged artist who could live from art without hiding her identity or hiding under a masculine pseudonym. History has been very different for many others, forced to remain anonymous because of imposing patterns of what is socially admissible or eclipsed by the figure of a man who knew how to make better use of others talent. Sofonisba was able to ironise on this question and paint herself while being portrayed by her teacher, whom she overpassed in pictorial technique. This work deals with the eternal theme that women could only serve to pose and be muses of inspiration.

Cave of the hands, Santa Cruz, Argentina.

Recently several studies have been developed defending the theory that it is possible to distinguish the female footprint in cave paintings. The Center National de la Recherche Scientifique (France) has shown that more than half of the silhouettes correspond to female figures. Undoubtedly, behind the authorship of these works, there are groups of women. Analysing the size of the hands drawn on the walls, a more recent study by Dean Snow, from the University of Pennsylvania, in 2012, shows that most of the paintings were done by women since 75% of the hands analysed are attributable to them.

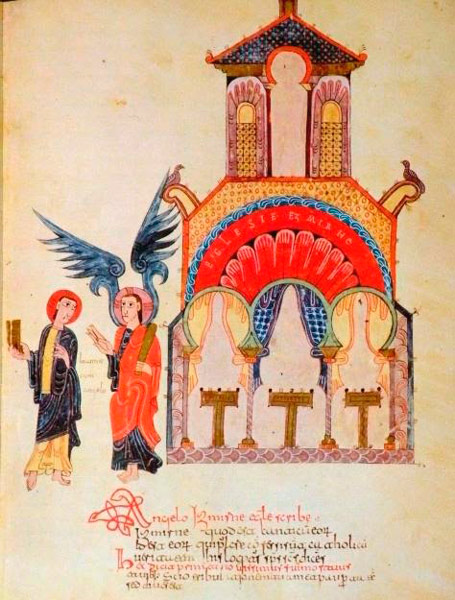

Page of Beato de Girona.

Another relevant figure is that of Ende, a 10th-century miniaturist who left her signature on the Beatus of Girona, a codex illuminated with commentaries on the apocalypse. In Medieval times the monasteries were mixed, although monks and nuns maintained a life in separate groups. This was also the case of the scriptorium of the monastery of San Salvador de Tábara (Zamora), where the book was concluded on July 6th, 975. In one of the pages, we find the signature of Emeterio, priest of the monastery and possible copyist of the manuscript, along with that of Ende, who declares herself painter and servant of God, "Ende pintrix et dei aiutrix frater emeterius et presbiter". This is the first woman artist in the history of Spain and one of the first whom we have news of across Europe.

Gerda Taro (left) | Image of a militiawoman in the Spanish Civil War by Gerda Taro (right).

Only a few know that behind Robert Capa, an internationally renowned name for his war photo report, there was a couple of photographers composed by the Hungarian Endre Ern? Friedmann and Gerda Taro. It is frankly difficult to distinguish which photographs belong to each of them. They worked in perfect harmony and were the first war reporters with shocking images that will remain for posterity. However, the fact of having chosen the masculine name of Robert Capa (Robert, by the actor Robert Taylor, and Capa, inspired by the filmmaker Frank Capra) led the whole world to identify Ern? with the author of these snapshots. Gerda Taro was the first female photojournalist of war, and finally died when she was 27 in the first line of combat, at the Battle of Brunete in 1937, while working to cover the Spanish Civil War for the French press. Because she always risked. She liked to get involved in the battle, to express the harshness and misery of the conflict.

Fumiko Neguishi.

Another situation is what the artists Fumiko Neguishi or Margaret Keane experienced. In both cases, these painters worked for others, until a moment when they refused to remain anonymous and to give up their talent for the fame of others. Fumiko Neguishi has recently sued the artist Antonio de Felipe for having fired her unjustifiably after working without a contract for him for 13 years, painting in the mornings many of the works that De Felipe signed afterwards.

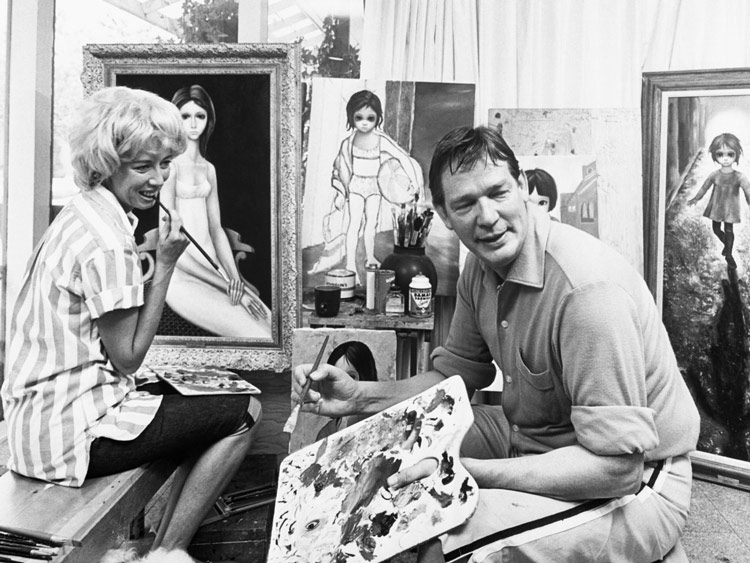

Margaret and Walter Keane in their studio.

There are many cases in which behind the success attributed to a single person there is actually a work of two, a creation in a symbiosis that prevents defining the limits of authorship that corresponds to each of them, as with Alma Reville and Hitchcock, Camille Claudel and Rodin, or Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. The case of Margaret Keane and her husband Walter could fit a priori in this scheme. However, the situation was very different. Margaret painted for her husband Walter, and apparently, both had agreed to present the works under the signature of Walter to make a way in the market, always more receptive to the male artists. Over the years and the incredible success of Margaret’s works without ever having a recognition of the real authorship, the relationship suffered and Margaret ended up denouncing Walter and claiming a compensation for her work, although in the process Walter denied the authorship of his wife. The funny thing is that this trial incorporated an expert evidence in which both were asked to paint live a piece in the courtroom. Walter was unable to do it. Margaret finished it in 53 minutes. It was a decisive evidence.