YOROKOBU CELEBRATES ITS 10 YEARS WITH ART MADRID'20

Feb 20, 2020

art madrid

Yorokobu magazine has just celebrated 10 years of serving creativity and its best stories. As Mar Abad, the magazine's founding partner, explains, «the most rewarding thing has been finding so much talent that I had yet to discover and observe how these people have become established creators».

This year, Art Madrid is joining forces with Yorokobu to welcome a group of illustrators and creators who are faithful to the genuine style of this medium which, with a decade under its belt, has managed to carve out a path for itself in the publishing sector, always maintaining the freshness, originality and a small irreverent touch that so characterise its publications. This twinning is also a double celebration, 10 years for Yorokobu and 15 years for Art Madrid, an occasion that deserves to be shared with the public at the height of Art Week in the capital.

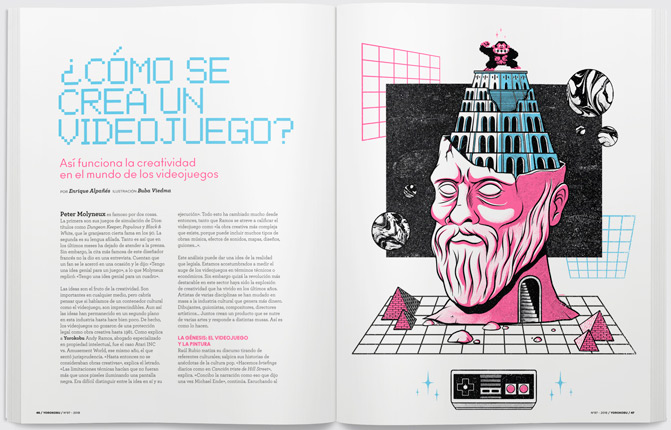

The booth that Yorokobu will have in Art Madrid is a small tribute to the trajectory of the medium, based on the discovery of potential talents, since the two selected artists were and are collaborators of the magazine: Juan Díaz-Faes and Buba Viedma.

The Asturian Juan Díaz-Faes will present his project Black Faes, the result of an artistic residency promoted by the SOLO Collection within its lines of patronage for visual artists. With the support of SOLO, this creator makes his work available to the public for the first time.

In Black Faes, the artist transfers his classic patterns to pieces which black is the main colour, created with the intention of being shared and enjoyed in domestic spaces.

Each piece has its name and its own history. Tuchelin, Bogey, F.Devillers, Blakinete,Mayan or BlackBoin are part of the gang of geometrical pieces that, thanks to the incorporation of Talavera ceramics, recovered books, woods or canvases, take shape and propose a different story depending on where we look at them from.

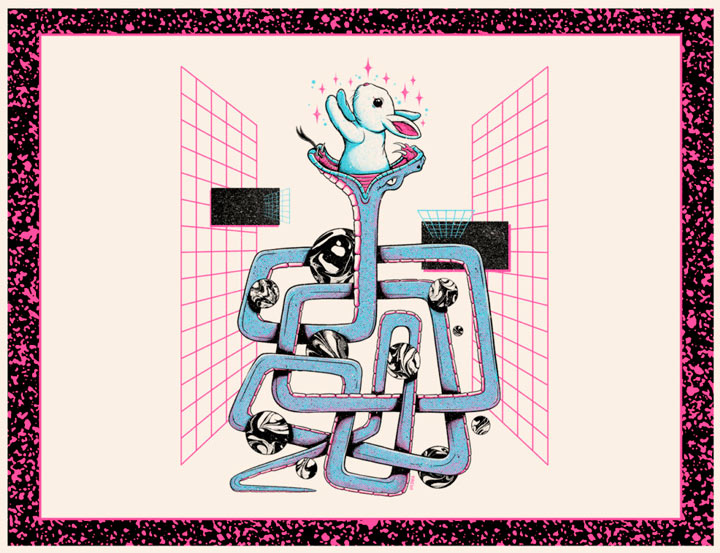

The second proposal from Yorokobu comes through Buba Viedma. The illustrations presented by the Madrilenian come subsequently to the series The rabbit and the snake.

Viedma continued investigating in his work about The Symbol and the archetypes of his dreams, about his own and collective unconscious, looking for the way to bring these symbols and their meanings to the new times, but, as he himself explains, "always freaking out about the right thing".

- - - - -

JUAN DÍAZ-FAES

Diaz-Faes draws, eats and laughs in equal parts. And if he's quiet, he gets bored. One of Yorokobu's leading illustrators, this Asturian artist, who has developed his career between illustration and muralism, is the author of 10 books and has collaborated with media such as GQ, El País or Ling, among others. He has also worked on campaigns for brands such as San Miguel, Nickelodeon, Ford and Vodafone.

- - - - -

BUBA VIEDMA

Buba Viedma is an illustrator and graphic designer born in Madrid. He grew up in a neighbourhood where going out into the street after sunset meant going home barefoot, so it was much more practical to stay at home watching cartoons, reading and, of course, drawing.

He had a long mili of printers, studios and advertising agencies. At the same time, he carried out freelance orders for small clients under the umbrella of Mentecalamar Studio. At the beginning of 2014 he decided to bet on the studio and work on his own.

He is a regular contributor to Yorokobu magazine, with whose collaborations he has won two ÑH awards and one APIM prize.

In his free time he cleans his house, does the laundry, cooks and fights against evil, although for the latter he does not have much time left.

Yorokobu will be at stand D6 in Art Madrid'20