INTERVIEW WITH: KEPA GARRAZA

Jan 27, 2022

art madrid

Trained in Fine Arts at the University of the Basque Country, the Bradford Art College in England and the University of Barcelona, Kepa Garraza (Berango, Vizcaya, 1979) began his exhibition career in 2004. From that time, he received various scholarships and awards.

Kepa Garraza's work reflects on the nature of the images we consume daily. For this reason, his work questions official discourses and calls into question the processes of institutional legitimation. The proposed reflection drinks from his interest in the construction processes of the historical narrative. In this way, Kepa invites the viewer to question the information obtained from the official media. His reinterpretation of reality is always ambiguous and confusing, full of subtleties and grey areas that invite the viewer to rethink the historical account and the chronicle of reality.

Interview:

What inspires you when creating?

Mainly I am inspired by current events of the reality in which we live. Basically, our daily life. The detailed observation of the facts and circumstances that most influence us in our daily lives. Above all, I am interested in reflecting on them and elaborating a rereading of reality.

What are you working on recently?

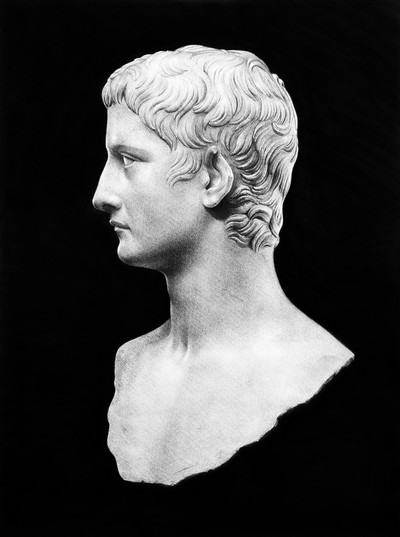

I am now working on a series of quite different works because the creation process has an essential digital component—something new in my creative process. Being concise and concrete, it is about creating elements of public sculpture (monuments) that do not exist from scratch and making a kind of assemblage in which I substitute monuments of diligent politicians, monarchs and revolutionaries from all over the world for these pieces of fiction, for these drills.

Tell us about your creative process.

My creative process is quite orderly, and I think it's a true reflection of myself. I imagine, like everyone else, it is always based on (or begins) with the concretion of an idea that is generated and matures little by little inside the head. Gradually it takes shape until it becomes something definite. Until I have that reasonably clear idea in my head, even with a very concrete image of the final works, I don't start the creation process per se. It is a very detailed process where the following phases are very established, and I rarely skip them. I have been working like this for many years, and I imagine it is a matter of economy of effort and comfort.

Are you participating for the first time in the fair? What do you expect from Art Madrid?

I have participated in the fair before. The truth is that it has always had a very positive result for me. With which, I hope that this year the result will be repeated and it will be a great fair if the health situation allows it.

Tell us about Kepa Garraza, the imaginary artist, your alter ego born in 1957.

Kepa Garraza of fiction is an alter ego born very close to my father's dates. He is a Kepa who becomes an excellent star in the art world, being quite young, in the early '80s, and ends up having a meteoric career that makes him a superstar. The life of this Kepa Garraza is narrated in a series of paintings that function as a kind of fictional biography where he is seen accompanied by illustrious personalities of the last 40 years, but none of his works are ever seen.

Is art for you a tool to criticize the art system itself?

Yes, in a way, but not only the art system but the entire sociopolitical reality. Bearing in mind that art is still a very faithful reflection of the world we live in, all my work has a component of social criticism. Or well, you want to invite thinking about certain concepts related to the economy, politics, history and social reorganization. Art, of course, falls within that objective.

It is true that perhaps a few years ago, my language and my works spoke more of the world of art, and now I deal with more general topics. But in the background, all the series and those interests are interrelated. They all arise from my obsessions and things that interest me.

Kepa Garraza participa en Art Madrid con la galería de Barcelona Víctor Lope Arte Contemporáneo, junto a los artistas: Carsten Beck, Dirk Salz, Jacinto Moros, Jo Hummuel, Mario Dilitz, Max Gärtner y Patrick Grijalvo.