INTIMATE SPACES. PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

Jun 7, 2018

art madrid

Within the online exhibition “Intimate spaces. Personal reflections” eight artists whose works are connected by the search of the intimate space live together. The images by Xurxo Gómez-Chao, Alfonso Zubiaga, Carlos Regueira, Soledad Córdoba, Rocío Verdejo, Andy Sotiriou, Ely Sánchez and José Quintanilla capture serene and solitary settings, empty spaces, open-plan rooms with which they invite personal reflection. The selection of images in this exhibition assembles around two areas: that of interior spaces and that of natural landscapes.

The individual is immersed in an everyday whirl leading him to a vital dilemma. A large part of our decisions is the fruit of the evolution of things, the imposition of standardised guidelines that surround us with routines of modernity, in the stream of the society of our time. However, the need to recover the essence of the human being is often imposed on this inertia. The return to spirituality, to inner balance, demands its place.

With the series "La Salita" the photographer Xurxo Gómez-Chao manages to give soul to walls and spaces in which the only outstanding element is an armchair. This way, he creates dreamlike environments within those interior landscapes where the absence of any other element confers a more intangible meaning.

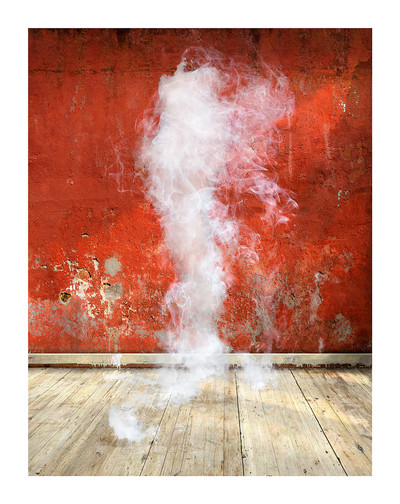

For her part, the lyrical scenarios of the series "Limbo" by Soledad Córdoba start from experienced and dreamy realities. Her images create visual poems, where silence, beauty, pain, fear or lack of communication are present and united by a fragile thread. Rocío Verdejo, likewise Soledad, introduces human figures in her compositions to unravel that tangle of feelings and emotions that gender violence implies. Her work "Crashroom" is a visual metaphor that manages to express the "not to exist inside".

Natural environments also offer a multitude of possibilities to show those sensations even if there are no walls, no borders, no limitations. We find naked landscapes that manage to convey a deep balance like those by Andy Sotiriou, whose series "Snowscapes" captures snow-covered fields crossed by random lines of vegetation, or Alfonso Zubiaga, who interprets the relationship between the land and the sea with images of high-contrast and great serenity in his work "Binario". In this same way, José Quintanilla also uses cultivated fields in which, suddenly, an anonymous and washed-out construction emerges. His project "My house, my tree" conveys a deep nostalgia with retro aesthetic photographs and ochre-pastel tones.

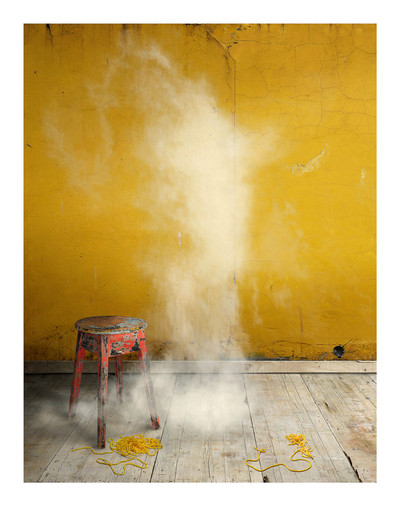

From a more dreamlike perspective, Carlos Regueira offers a dramatic vision of wooded landscapes. His "Paisajes pervertidos" reflect a morbid beauty, perhaps threatening, but at the same time reveals formal serenity and balance. These images emerge from the mist of memory and interpellate the viewer. In a similar line evolves the work of Ely Sánchez. In his series "Heridos" seeks to reveal that everything we see is an artifice, a translated image, credible but not real. On the other hand, in "Sueños geométricos" the artist focuses on the beauty of the lucid dream to experience what in real life is not feasible, thus releasing his most intimate identity.