ONE PROJECT PROGRAM, A DIALOGUE, A PAUSE, A REFLECTION

Jan 24, 2018

art madrid

The One Project Program, curated for the fifth consecutive year by Carlos Delgado Mayordomo, has become a true showcase for new talent. These are the 8 projects of the 13th edition of the fair.

Alejandro Monge, Candela Muniozguren, Antonyo Marest, Carlos Nicanor, Bernardo Medina, Jugo Kurihara, Aina Albo Puigserver and Vânia Medeiros are the 8 artists selected by the independent curator Carlos Delgado Mayordomo to form the One Project Program at Art Madrid'18, a program designed on young and mid-career artists with specific projects developed for their exhibition at the fair.

In One Project, 8 artists design a specific proposal for an individual stand, these 8 projects, with a resounding and coherent entity, they dialogue guided by the hand of the curator. The objective is to captivate the public, allowing them a break within the commercial context of the art fair. "One Project has served to establish a dynamic, open and polivocal relationship with those visitors interested in establishing a more deliberate and reflective view within such an overwhelming and oversaturated context of information as it is a contemporary art fair", explains Carlos Delgado Mayordomo.

In the edition of Art Madrid'18, One Project is made up of the following projects:

Alejandro Monge (Zaragoza, 1988) with 3 Punts Galeria (Barcelona). Endowed with a solid plastic formation and interested in the complex channels of figuration in the current creation, the recent research of Alejandro Monge seeks to investigate the economic contradictions of our present. Conformed as a series and grouped under the title "European Dream", its latest proposal is organized around the conceptualization of money as an index that modulates our understanding of the world in a context mediated by the financial crisis of 2008.

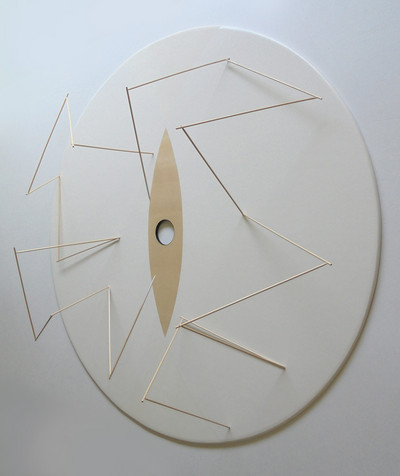

Candela Muniozguren (Madrid, 1986) with Bea Villamarín (Gijón). The sculptural work of this artist poses an intimate communication between her creative developments, where minimalist forms dominate, and the multiplicity of chromatic effects.

Antonyo Marest (Alicante, 1987) with Diwap Gallery (Seville). The jumps of scale, the exit of the interior of a museum to the clarity of the streets, the urban style shared with the public in the form of painting, sculpture and photography. Marest has geometry as a symbol of personal growth and positivism about architecture, line, plane and color. From Seville, DIWAP Gallery works immersed in the most current contemporary art, with the aim of approaching a demanding public and always in constant search for new contributions to the local and national art scene. With a special inclination towards young and urban art, DIWAP Gallery has been defined by the representation of its artists and their works. In short, DIWAP invests in the investigation of new lines of contemporary works and new forms of curatorial projects, preferably linked to mural art and installation.

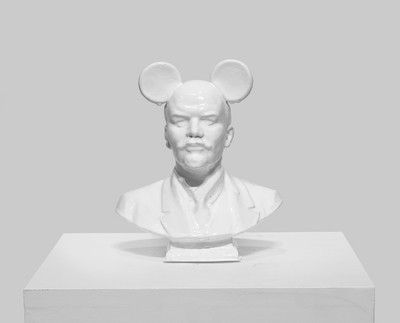

Carlos Nicanor (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1974) with Artizar gallery (La Laguna, Tenerife). Brossanian sculptor, his creativity aspires to create works that are at the same time caustic alteration of the object and its meaning. The sculptural intensity of Nicanor is poetic in nature.

In 1989, in the center of the city of San Cristóbal de La Laguna, on the island of Tenerife, the Artizar art gallery began its journey, with the main objective of making known and establishing a meeting point for art in the Canary Islands. A wide range of artists from the islands has passed through its walls, from paintings of the XVIII, XIX and XX centuries, contemporary painters of recognized national and international prestige and, of course, young artists who have grown up with the gallery.

Bernardo Medina (San Juan, Puerto Rico, 1965) with Nuno Sacramento (Ílhavo, Portugal). Distinguished by his ability to integrate objects found in his travels, to create beautiful and strong abstract pieces, the artistic development of Bernardo Medina has been the result of a long process of study and experimentation from the everyday to be projected in paintings and sculptures with a strong visual poetics

The Nuno Sacramento Gallery has been active since 2003 with the opening of its first gallery in the city of Aveiro, Portugal. In 2009 he moved to the nearby city of Ilhavo, to a space specially designed for a gallery of contemporary art, where it remains until now. It annually develops around six solo and three collective exhibitions, in the disciplines of painting, sculpture, photography, installation and video.

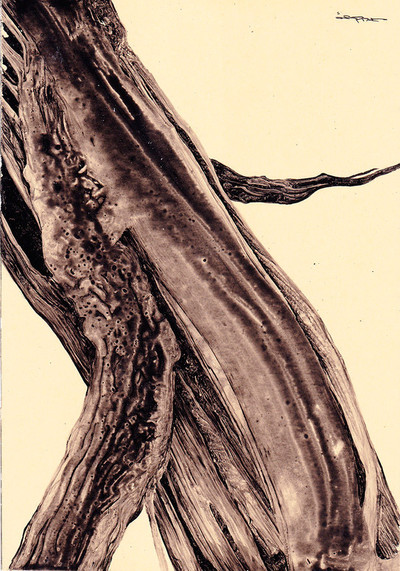

Jugo Kurihara (Japan, 1977) with Pantocrator Gallery (Suzhou, China). In his works, he combines Asian and European artistic languages and successfully converts it into his own expression: images of a disturbing beauty, capable of referring unpublished worlds, of tracing complex writings and, above all, of mobilizing the spectator in front of a flowing painting that always seem to be about to stabilize in a specific iconography.

Pantocrator Gallery is a project for the dissemination and production of contemporary art by emerging international artists in any of its disciplines. Pantocrator Gallery, as a nomadic project that is, has its physical headquarters in the Chinese city of Suzhou, but it has visited cities such as Barcelona, Berlin or Shanghai in which they continue to work eventually. Pantocrator Gallery works as a cultural bridge between Asia and the West.

Aina Albo Puigserver (Palma de Mallorca, 1982) with Pep Llabrés Art Contemporani (Palma de Mallorca). Experiences that go beyond the senses, Aina Albo investigates and approaches her emotions and sensations to understand them better, giving them shape and color in an attempt to turn the abstract into concrete.

Pep Llabrés, after a long journey in the sector, opened his own space in April 2015, and since then focuses his activity in the field of contemporary art, giving visibility to young values with new languages of expression, without forgetting the contribution to the art world of artists with more experience, both national and international.

Vânia Medeiros (Salvador de Bahía, Brazil, 1984) with the RV Cultura e Arte gallery (Salvador de Bahía, Brazil). Visual artist and editor whose work deals with human and emotional maps and creates subjective cartographies and ways of graphically expressing the experiences of a traveling body in the city.

RV Cultura e Arte is a contemporary art gallery based in Salvador de Bahia focused on works on paper (drawing, painting, collage and printing processes) and emerging Brazilian artists. Inaugurated in 2008 by Larissa Martina and Ilan Iglesias, RV Cultura e Arte carries out a diverse annual program offering at least four exhibitions as well as workshops, talks, guided visits and viewings that foster a closer relationship with the local community, collectors and curators . Since 2011, RV Cultura e Arte has also developed an editorial project with artist books and graphic novels.

A mixed and international selection, different perspectives and starting points that find, in One Project, common frequencies in which to dialogue and share a handful of concepts. However, as Delgado Mayordomo explains, "these lines work only as a tool box to think about the work of artists without denying the relevance of other constructions".