YOUNG ART: TALENT IN AND OUT OUR BORDERS

May 20, 2020

art madrid

For the last decade, 'millennials' have become a trendy term and we heard often about the concerns of a new generation that has broken into the new millennium to address many of the challenges that the future has in store for us, with all its uncertainty and ambiguity. It is undeniable that any change, even if it generates a benefit, comes along with a time of transition in which the foundations and the structures that we believed to be immovable begin to crumble. The intrinsic evolution of these phenomena is linked to a sense of uneasiness that societies face from the collective support and from the need to open the debate on the concerns, as new and well-known, that marks our evolution and the fate of our time.

The new generation creators have made their way on the art scene, focusing part of their work on addressing topics that are intimately connected to the reality of the moment. It is the channel to subvert classicism, to make pieces that show commitment to the environment, to make their works a manifesto that transcends mere contemplation and becomes a form of plastic expression of a shared feeling.

In Art Madrid, we have been able to verify this growing movement of artists of the new millennium that are detached from prejudices and archetypes to focus on issues of enormous social impact that affect us all. The number of young creators has been increasing in the latest editions of the fair, and it is also remarkable that the paths of expression chosen by many of them are fueled by artistic hybridization, the fusion of techniques, exploration beyond the image, the search for a second reading.

Today we remember the work of some of these authors who have visited us at the 15th edition of the fair and we get closer to their work.

Among the artists who show a concern for the excessive consumerism of our time, the depletion of resources or the future of an alienated society, we highlight the case of Alejandro Monge (Zaragoza, 1988) and that of Chen Sheng-Wen (Taichung, Taiwan, 1993).

Monge's work has on many occasions sought irony about the tangible value of money and superfluous appreciation of material things, often with art installations that replicated stacks of bills in bank deposits or safes. His latest, more pictorial works show a dark side of global society, drowned in its energy production needs and in the polluted and aggressive atmosphere in which we live in large cities.

For his part, Chen Sheng-Wen proposes a much more delicate hand-made work in which he represents the delicacy of nature and its need for care, reproducing with embroidery and mixed technique numerous animals from our immediate environment. Sheng-Wen's decision to use recycled materials, rescued from the forests usually inhabited by these beings, shows the lack of care for mankind and the degree of exposure to which these species are subjected.

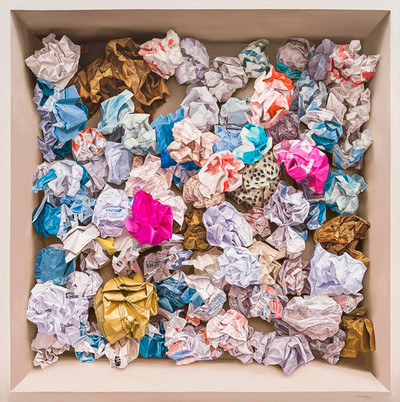

Onay Rosquet (Havana, 1987) moves in a similar line with a work that transmits a great aesthetic balance but allows multiple readings. Their boxes of papers, sometimes folded, others wrinkled or stacked, make us think about the problems of lack of communication in the society of our time while posing the dilemma of the appropriate use of resources and the generation of waste with high environmental impact. Of these two ideas, the first is the main line of his discourse: the era of hyperconnectivity leads to the paradox of the lonely, abandoned individual, who has lost the ability to interact in a non-technological way. A simple glance at his pieces makes us think of the thousands of words that do not arrive, the things that are not said, the feelings that are repressed in a context dominated by the pretending of happiness and the fake of perfection.

Other creators emphasise social inequality. Nina Franco (Rio de Janeiro, 1988) tries to represent gender inequality and the harassment that many women suffer on a daily basis, especially in some patriarchal societies. Her work reflects a great concern for contemporary socio-political conflicts.

For his part, Adlane Samet (El Harrach, Algeria, 1989) treats inequality from the perspective of its immediate environment, raising the question of where certain societies are located on the global scene, in which there seem to be first-class and second-class countries. His work is visceral and colourful, and the impulse of the brush strokes itself externalises that authentic and pure vitality of the environments not contaminated by imported ideas.

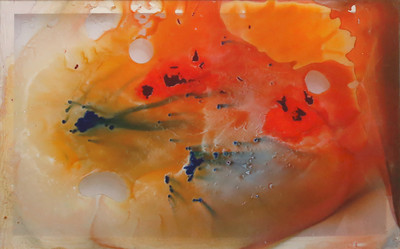

We also highlight the work of Cristina Gamón (Valencia, 1987), an artist who explores the evolution of painting with the incorporation of new materials and the integration of plastics as support. Her works remind us of landscapes of arid zones, laboratory experiments or the iridescent drawings of oil on water. She aims to offer a contemporary painting with representative materials of our time, without losing the expressive force of colour.