AURORA VIGIL-ESCALERA, 35 YEARS IN THE WORLD OF ART

Feb 14, 2020

art madrid

The Asturian gallery owner Aurora Vigil-Escalera is celebrating 35 years of professional career. Aurora came into contact with art when she was 17 years old, helping her mother in an apartment on Ezcurdia Street in Gijón. There, Aurora lived great artistics talks and saw an endless number of authors who today are part of the list of artists in her gallery. In 1984, Angelines Pérez, Aurora's mother, opened the Van Dyck Gallery with her father Alberto Vigil-Escalera.

In 2015, the Van Dyck gallery closed its doors and a new cycle began for Aurora, who opened the gallery that bears her name in Gijón that same year. Today, Aurora Vigil celebrates 5 years of the gallery with the firm conviction that vocation, dedication and enjoyment are the keys to success as a gallery owner. Following these parameters, Aurora Vigil presents in Art Madrid a careful selection of art works by eight multidisciplinary artists with different approaches and lines of discourse, all of them with established artistic careers.

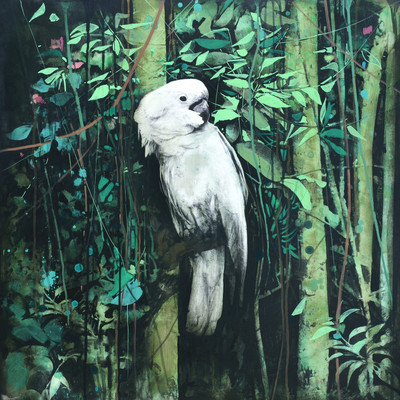

The artist David Morago(Madrid, 1975) will exhibit his well-known paintings with botanical and animalistic representations, images that are already part of the artist's particular universe and iconography. As if it were a Natural History cabinet, Morago provokes with his portraits of animals and plants, an effect on the viewer that takes him directly to the artist's cabinet of curiosities and wonders.

From the purest figurativism, we move to the dream universe of Rafa Macarrón (Madrid, 1981),an unconditional artist of the gallery with a personal style and a unique language, represents in his works brightly coloured figures with hydrocephalus and filiform limbs, as well as unusual and unique characters that claim all the prominence of the work.

The three-dimensional plane will be represented at the Aurora Vigil stand by the works of the artists Herminio (La Caridad, Asturias, 1945) and Pablo Armesto (Schaffhausen, Switzerland, 1979), the latter more focused on his work towards an experimental space where sculpture and painting coexist with the immaterial character of light and shadow, together with technology and science. Herminio, whose work has accompanied Aurora in all the editions of Art Madrid, captures in his light and ethereal sculptural pieces his most important concerns as an artist: balance, perpetual movement and electromagnetism.

Colour and matter in their purest expression are condensed in the works of Juan Genovés and Ismael Lagares. The Valencian artist Juan Genovés investigates with the static movement of painting, where the crowd becomes the reference to talk about the problem of painting and visual rhythm. On his part, Ismael Lagares with a colourful invoice and a vibrant and fast brushstroke, distorts reality playing with textures and volumes.

Gorka García (Cádiz,1982) is one of the youngest artists and with more projection of the gallery. In his paintings, uninhabited landscapes and ruin dominate, these two elements being the main germ of his compositions. The poetics of ruin and the deep analysis of composition and forms in his works define the artist's discourse.

In addition to Gorka García's uninhabited landscapes, the Asturian artist Dionisio González will be presenting for the first time at the Fair a selection of his "imagined architectures ", photographic montages where the artist inhabits his own abandoned urban landscapes, in ruins or devastated by natural disasters.

We interviewed the "artist architect of desires " to tell us about the main ideas and concepts he puts forward in the pieces he will be exhibiting in Art Madrid, and how in his works he is able to manipulate reality to improve it:

The gallery Aurora Vigil-Escalera presents your work in Art Madrid for the first time, how do you think your artwork will fit in at the fair?

Aurora has been in the art world for 35 years. Her professionalism and the quality of her program are undeniable. Being a gallery on the outskirts of a sparsely populated city in Gijón, the ex-centrism makes her work even more complex. When these qualities, both human and professional, are present, it is easy to fit in the artistic work and I hope that this will be the case during the duration of Art Madrid, where we will present "Dauphin Island" and "Cartografías para a RemoÇao".

In your art works you reflect on concepts such as construction and destruction, ruin and habitability, what elements define your "dystopian" ruins?

"Dauphin Island" maneuvers over an island, in the state of Alabama, that has suffered numerous natural disasters and for which I have proposed architectural projects "bunkerized" that configure new habitable structures of resistance for those spaces previously devastated by hurricanes like "Katrina". The work on Brazil's favelas is related to the desire not only to intervene but to interfere in an extreme problem, either as a designer or as a social regulator. That is, to establish a social role in defense of these settlements by proposing not their eradication but their sanitation, which is nothing more than intervention based on the already existing "cartography". The favela shows us how urban architecture can be an issue that is resolved through a popular logic.

They talk about you as the "healer of cities artist", have they proposed you to bring some of your projects to life?

I have had many offers in this sense, because the constructive approaches, which appear in my visual work, have both a critical or theoretical approach and a urban and architectural planning behind. That is to say; they can be built or consolidated in the empire. But, I would only consider executing them if they are proposed for spaces that denounce and the ideology that has articulated them that, almost always, operate from the vulnerability or social problematic.