PIGMENT GALLERY: FROM THE MOST MODERN FIGURATION TO THE PUREST ABSTRACTION

Feb 10, 2020

art madrid

The Barcelona gallery Pigment Gallery is participating for the first time in Art Madrid with a selection of works ranging from the most modern figuration to the purest abstraction. Pigment participates in the fair with five local artists and one Italian artist based in Barcelona. They are: Aurelio San Pedro, Marta Fàbregas, Adalina Coromines, Rosa Galindo, Rosanna Casano and Alberto Udaeta.

The multidisciplinary artist Aurelio San Pedro (Barcelona, 1983), uses different media and techniques both traditional and digital to express himself. In Art Madrid, Aurelio San Pedro will present works belonging to his series "Libros" which he tells a story about the concept of time by using as signs of his compositions book songs, pages, covers and cut-out words, structuring them within a surface which he achieves the final sculptural piece. In this way, the artist creates his own symbology and artistic imagery.

Each book he uses does not contain just a story, it is full of experiences and memories of the author himself or of the characters in the story told, and in many cases of the artist himself. The artist plays with time, conveying his experiences through fragments of books with variable times, using repetition, gathering and order to symbolize the concept of the archive.

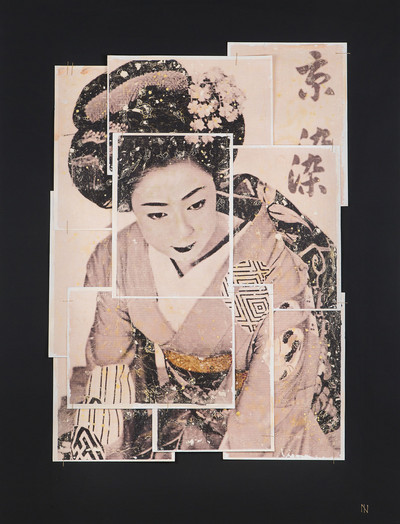

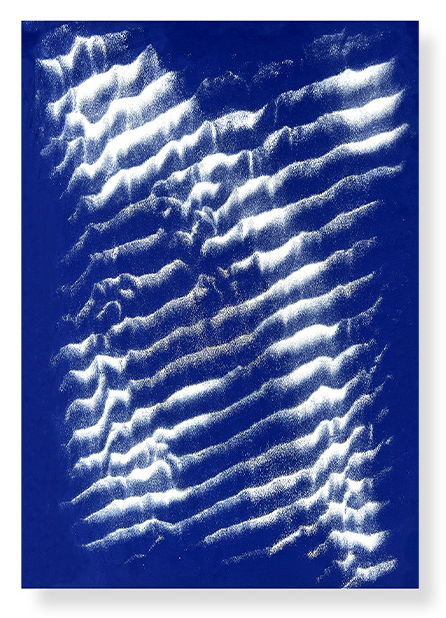

The concept of time is also used in the work of Marta Fàbregas (Barcelona, 1974). In her series "Colonizadas" she rescues photographs of 19th century women from different social and working environments who have been subdued simply because they are women. All of them, in one way or another, were colonised by society, which took away their identity, their future, their desires and their dreams. Marta Fàbregas gives visibility to women who never had it.

Fàbregas uses photography as the basis of her work, but she alters it through the technique of transphotography by combining photographs from digital archives with precious fabrics, using collage techniques, inks, gums, which she manages to create textured surfaces. These fabrics are attached to the image by means of digital retouching, complemented by collages and transphotography.

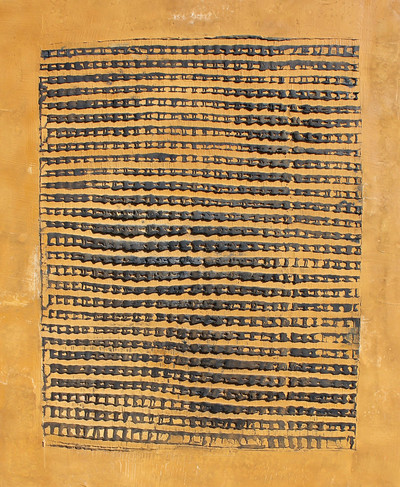

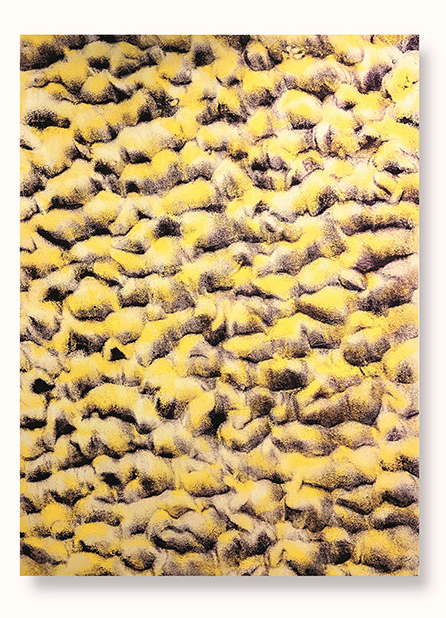

Adalina Coromines (Barcelona, 1963) by means of different techniques in which natural pigments, earth, sand and ecological materials in general are found, creates a suggestive work, where the sensation of the passage of time is transmitted by the appearance of the piece already aged, being the textures and the patinas the elements that contribute those effects of illusory wear that the artist manages to transmit, and that coexist in her inner world. The big formats of her works help the viewer to enter into the deepest mysticism of the artist.

Coromines intervenes the materials used in her art work, texturing them with different tools, some of them coming from her own inventiveness, and she manages to create bas-reliefs that give depth to his work, in which large horizontal wooden boards are superimposed on metal ones. A beauty achieved through modesty and simplicity.

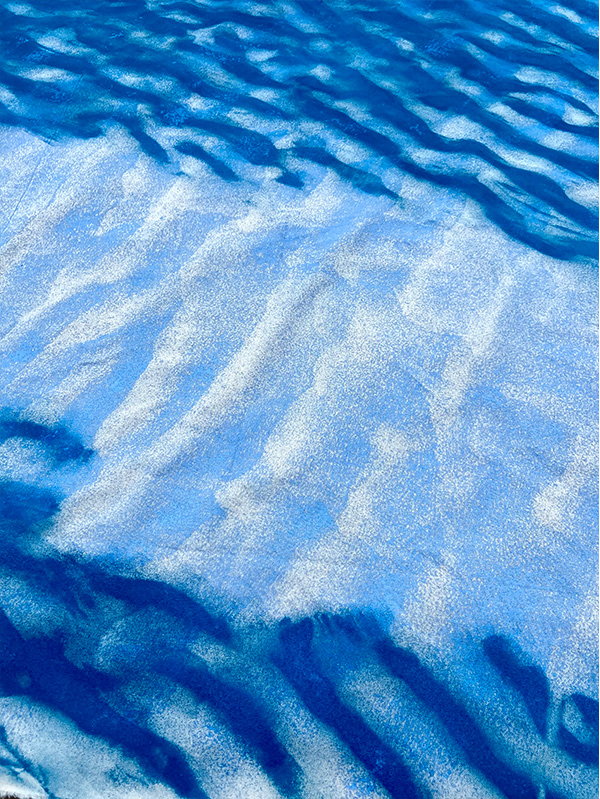

The dream images of the artist Rosa Galindo (Barcelona, 1962) transport us to an imaginary territory of delicate organic forms that she achieves by playing with different research processes, mainly with the technique of reverse Plexiglas painting. This plastic material allows to obtain transparencies and opacities in which the color vibrates of a special form in its gestural brushstrokes, managing with it to create a fictitious atmosphere where it manifests his philosophy on the place of the world in which the humanity must be located.

His works lead us to a world of meditation and personal reflection through the weightless sensation that the organic forms superimposed on his colorful backgrounds arouse.

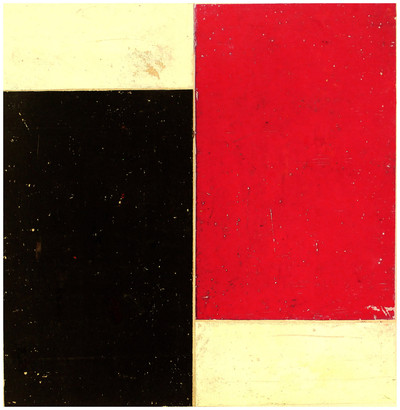

Rosanna Casano (Marsala, Italy, 1968), settled in 1989 in Barcelona, the city where she forged her artistic career. In Casano's work geometric forms, symmetry and patterns predominate, some of her pieces remind us of architectural structures ordered with simple forms, others start from more organic forms that tend to be figurative.

“In my work, different ways of composing coexist that are complementary. There is a tendency to order by means of construction and form, structuring a space, geometry creates a place where I think I am what I feel. And there is a tendency to leave the matter that I express, open or uniform, organic or mineral matter, where perhaps I think I feel what I am.”

The wrought iron sculptures by Alberto Udaeta (Barcelona, 1947) are based on experience and history. Using traditional techniques, some of which are typical of craftsmanship, the artist creates delicate structures based on assembled geometric elements that fit together. Udaeta seeks the splendour of forms through matter.

The artist condenses in his trajectory his formation and experience as an industrial engineer and his more profound investigation in the field of iron sculpture, experimenting with cast iron in the workshop he set up in Barcelona in 1982 in a former cork factory. ”The metals, fumes and gases that clutter workshops and foundries have partially spoiled my sense of smell, which is why I remember with nostalgia the smells I perceived as a child, when I returned to my great-grandmother's farm in the car. Fabulous smells of earth, water, freshly mown grass and also of horses, stones and snakes. But above them all there is still the bright, sharp, metallic smell of the edge of the dalle, very similar to that of my iron sculptures".