QUINTANA MARTELO INTERVIEW. "PAINTER AND MODEL" IN ART MADRID WITH THE GALLERY LUISA PITA

Feb 18, 2020

art madrid

"The process, precisely that path, is perhaps what interests me most in my dialogue with painting."

Quintana Martelo (Roxos, Santiago de Compostela, 1946), participates for the first time in Art Madrid represented by the gallery, also from Santiago, Luisa Pita. The Galician gallery presents a monographic proposal that includes a series of sculptural and pictorial works from the project "Painter and model, P&M", where according to the artist, the creative process is the key to his dialogue with the painting.

Manuel Quintana Martelo has among his multiple commemorations, the Galician Culture Award in Plastic Arts, sponsored by the Xunta de Galicia and is also the President of the Royal Galician Academy of Fine Arts.

Luisa Pita is participating this time in Art Madrid with a monographic proposal. What pieces by Quintana Martelo will we find at the Fair?

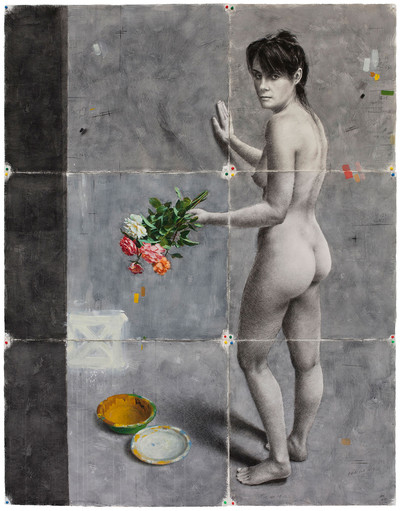

Indeed, it is a monographic proposal where I resort to an idea that has already been, worth the redundancy, recurrent throughout the History of Art and that other artists have already touched. One of the best known is the series "The painter and the model" by Picasso, or the representations which Lucian Freud has painted himself with his model, or we have even seen Rembrandt, Goya, different artists who have resorted to this kind of cornerstone of the "painter and model". For this reason, I base the idea of the whole project on a large central piece that is at the same time the definitive piece, the one that opens and closes this circuit where I integrate all the elements that revolve around an artist's studio. We can find both the human model, as other constant elements in my work, and the working tools that coexist with me in the studio.

Currently, you are one of the most renowned Galician creators, can you tell us some curious anecdote about your career as an artist?

I think that all artists have at some point experienced things that have been surprising. For example, I've had to dismantle a piece in the street because it didn't fit in the doorway or anywhere else in the house of a client who bought it from ARCO in the 80s, or I've had to climb up other pieces with ropes on a façade. And then I have some curious anecdotes, because sometimes, when you do landscape in the street, you take elements from the surroundings and situations always arise with the public. A curious one that happened to me in Madrid not many years ago, maybe 4 or 5, when I was working on the series of "Containers" of those that are located in the streets, I saw one that caught my attention, I took my camera and went to the center of the street to capture it in the angle that I was interested in, to capture the light and so on, and suddenly a worker came out with a wheelbarrow and says to me: "hey, hey, what are you doing", and I say: "a picture", "but are you from the City Hall? to which I answer: "no, no, I just want to take a picture to paint it", then he answers: "ah well, look, the truth is that yes, you need a coat of paint".

On another occasion, in an exhibition in Caracas, the penultimate day a man comes to talk to me and tells me that he is interested in my exhibition and all the paintings I had not sold. This took me by surprise and I told him: "well, we'll talk and see what you have to offer", then the gentleman said: "let's see, I want these works because when I see something I like I buy it, I take it with me, at home I paint it a little over, I erase the signature and sign it as mine". And then I point out: "you know what I say, you can go home and paint, because of course you won't touch these paintings".

In your artworks there is usually a confrontation between the object and the plane, between abstraction and figuration, what do you want to achieve with this dichotomy?

In some way, within this dichotomy of abstraction-figuration or representation-non-representation, I try to maintain the plane as the main element and what is understood as two-dimensionality of height and width, the integration of the work within a given context; and when I work on this plane I try to create a fusion between what is figuration and non-figuration, always thinking about integration. This is something that already haunts me, although perhaps in the last 20 years my work has been more clearly accentuated. But since my beginnings in Catalonia there was a part of me that was very creative with the object, with the model, with the situation, with the somewhat academic context of painting, and there was another part that was what I began to learn and live in Catalonia which was the contemporaneity of abstraction, discovering abstract artists that I didn't know, seeing in museum exhibitions those abstractions that I used to see only in books, and I started to be very interested in that language, especially when I discovered the American abstract expressionists, who were the ones that stayed in my retina with more intensity. From then on, and for the last 20 years, I have maintained this language.

In your work you practically deal with all the artistic disciplines (drawing, watercolour, painting, sculpture, collage) and it is incredible how you master the sculptural technique, can you tell us what is the process you follow until you reach the final piece?

As you yourself say, it is the process, precisely that path, that interests me most in my dialogue with painting. It's something that always concerned me and interested me, and in recent years I've magnified this idea of showing the process, and it's also what I manifest in this project for Art Madrid. All the little itineraries and twists and turns that are involved in making a work or carrying out a piece appear. This whole process interests me very much. The encounter, the journey through the painting, is something I am very passionate about, always translated into the pure exercise of painting, which is something I cannot let go of, even though at some point in my life I came to abandon painting, but it was something very punctual because I immediately realised that I could not do it. The sculpture appears at a certain moment when I realize that with the volume and with the three dimensions in reality, and not in the plane, I can turn around the model. This allows me to make an infinite number of drawings, which is what in some way brings me closer to the three-dimensional, which in the plane and in the painting I wasn't very concerned about, but there I am attracted to it. To be able to turn the model, to be able to see it in all the angles and to draw it a thousand times around.

How does the project "Painter and Model, P&M" that you are presenting at the Fair come about? How do you think this project will continue to evolve?

It's not the first time I've resorted to monographic projects. At the end of the 70s I made a series called "Chronicles from Rembrandt", which was based on the painting "Woman at the window" by this author. This, together with political moments of the time that called my attention, such as the revolts in Nicaragua or the political situation in Spain, interested me and integrated into my painting.

On another occasion I dedicated portraits to my friends, collectors and artists. I painted them without them posing, through a photograph or an image I retained. In the series "Containers", which is very significant and I hope to show it complete within a year, I worked on street containers as if they were an anthropological value of contemporary urban architecture, elements that at that time are part of architecture, like large still lifes with waste, but I am attracted by their light, their impact, their image, and with this I spent about 6 years working.

At this moment I have started with the series "Painter and Model" because I don't want to close it in the "Painter and Model", because it is a bit typical. I want to open with it the study to a model that is not material, but a human model that has life, that moves and in that sense, this is a little bit the beginning of that work and the end I can't predict, it is always unsuspected. It is precisely this point of uncertainty or ignorance that attracts me.

What do you expect from a fair like Art Madrid?

I've known the Art Madrid fair practically since it started, and it's a small fair that was born a little off the back of ARCO, which is, so to speak, the big fair; but it's a fair that, on the other hand, doesn't have the managerial corsets, especially in the last few years, that you see at ARCO, that you have to go with a certain "uniform", with certain proposals, and where it seemed that everyone proposed absolutely the same thing. I think that Art Madrid is more open to that dialogue and you can see a pictorial or artistic context as wide as the one of ARCO, but without those weird gestures of turning the nose up at figuration or an artwork that is within what ARCO did not defend very much, which is the value of the artist within his work, the figuration or the figurative context, etc. I have some expectations that will also depend on the public when they come to Luisa Pita's booth and see my work.