SHAPE AND COLOUR IN ART MADRID

May 30, 2018

art madrid

The abstraction is a style emerged in the 19th century that gained strength progressively until reaching a large presence in the art world. Figurative art follows its own evolution, but it does not always achieve that same expressive potential. As abstract art consolidates, the game of creators in the combination of shapes and colours becomes increasingly complex. The power of the stain, the communicative value of the void, the absence, the strokes or the contrasts serve to recreate a universe of thoughts and emotions more difficult to capture through material and tangible elements.

Many times abstraction is achieved with the combination of these two artistic tools: shape and colour, used with intention and consciousness to build a complete narrative. The history of art, however, has offered us examples in which both elements can live separately. Before the Renaissance, the form was the one that prevailed over the colour, which was just a simple complement. The contours, the volumes, acquired a presence of their own, with an autonomous and self-sufficient expressive load in which colour, rather, had no place. It is afterwards when colour begins to acquire relevance by itself. Caravaggio, with its chiaroscuros, will give it the importance it deserves, the figures will no longer be flat, they will highlight the volumes and textures that make their way between a rich and diverse palette.

Although during Realism, form and colour will be comparable, with the impressionists colour and shape no longer exist, only the air - light relation will be real for the painter. This way, the light will be the real subject of the painting. The quality and quantity of it, not the line or the colour, will be what will offer one or another visual configuration of the object. However, Post-impressionism, among other things, supposes a recovery of the importance of drawing and of the concern to capture not only the light but also the expressiveness of things and enlightened people.

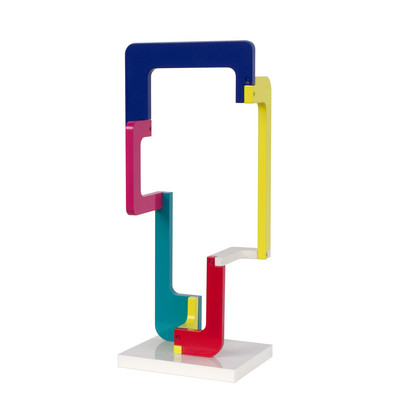

Form and colour and their connection to abstract art will be the elements that stand out in the work of the nine artists of the exhibition "Shape and Colour in Art Madrid". Thus, for the sculptor Carlos Evangelista, everything maintains a perfect order. His style is based on geometry, on the purity of simple forms and the multiple possibilities offered by the combinatorial development of simple modular units. Candela Muniozguren, for her part, proposes an intimate communication between her creative developments where minimalist shapes dominate and the multiplicity of chromatic effects. "Senbazuru", alludes to the old Japanese legend in which health is promised to anyone who manages to build a thousand origami cranes. For this, the artist combines the use of a single colour with the abstraction of planes, curves and diagonals that come together to result in a dazzling work that recalls those traditional Japanese folds.

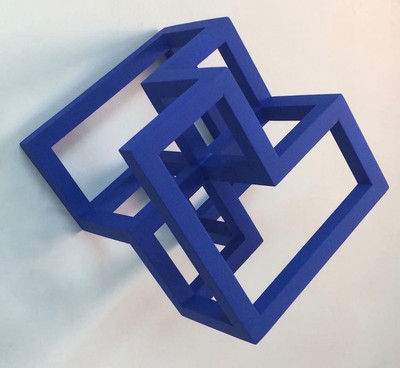

On the other hand, Rafael Barrios plays with shapes altering the laws of geometry, fabled volumes in space. His sculptures rise above themselves defying the rules of space, relieving bodies subject to gravity. "Hondos" or "Mural" are identified by their dynamics, by their lightness, by force and by the magnetism that they print with the purpose of each of them reaching the spirit. And we can not forget, the playful use of the shape and colour that Willi Siber performs or the exploration of pigments used by the Sevillian artist Isabelita Valdecasas in Cosmogonías.

The lines, shapes and colours of the language of the artist from Elche Ramón Urbán are born of the abstract and the poetic. It stands out the coexistence between the rotundity of the clean space drawing, of certain coldness, and the intense or soft footprint of the painting that lends warmth and ornament to the elemental form. In "Secret Artifice" the circles melt to confuse, lines that play with verticality, spheres unimaginable for their composition... they make Urbán's play a game of life and tranquillity.

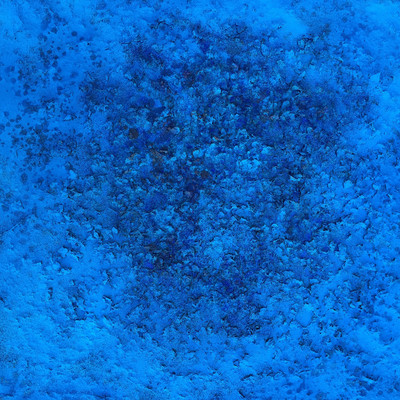

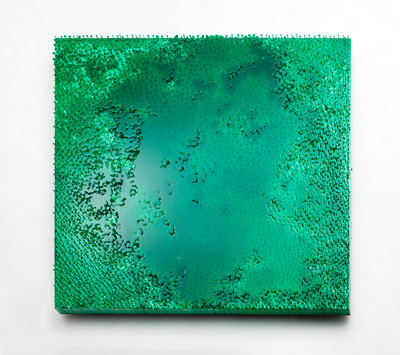

As for painting, we have chosen works such as those in the series "Flights II" by Nanda Botella, where light, colour and strength represent the elements of expression for this artist. However, the ethereal colour palette used by the abstract painter Sylvie Lei produces disconcerting paintings that relate to the problematic nature of virtual reality in the contemporary social context.

For his part, the Catalan painter Gerard Fernández Rico turns the line into the true protagonist in "Through the line". A diverse and complex path which the artist approaches in a millimetric way as if he were looking through a microscope. A line that together with the explosion of colour generates a vibrant sensation, a fresh and dynamic air in each of its pieces.