WHO SPEAKS AND WHERE? LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN AT ART MADRID

Jan 6, 2023

art madrid

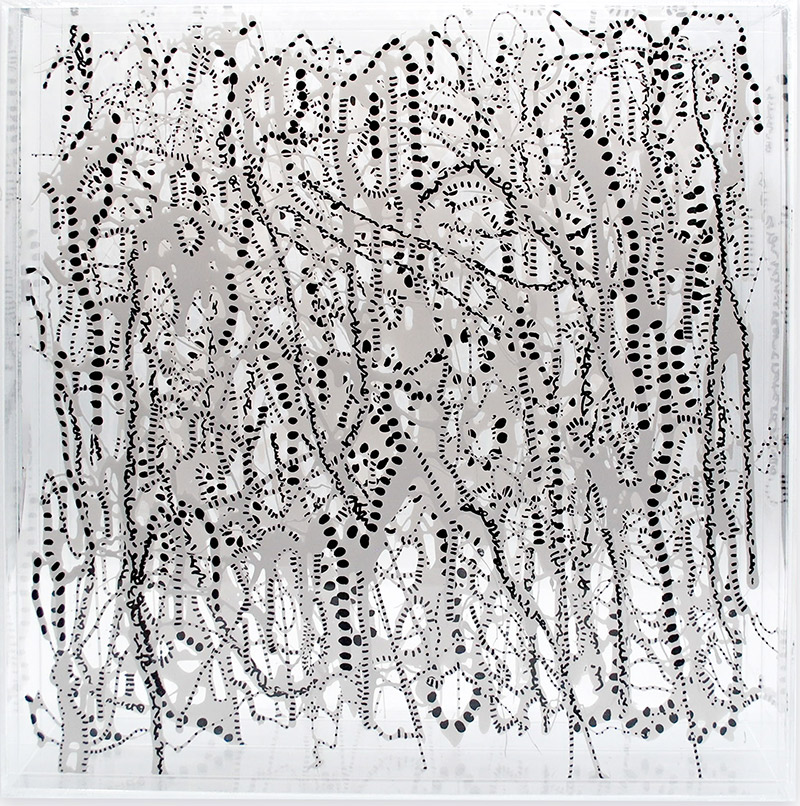

The artists and their works move narrative discourses presented before us with an expansive effect. Although inhabiting a geographical space, belonging to a specific social class, and having specialized training... are factors that define their work. Others, uncontrollable by the hand of flesh and blood, can change their perspective on life forever. This is precisely what happens with the creators who come to Art Madrid from further away, and we would say, those who have ventured across from the other side of the sea:

Adrián Socorro, Matanzas, (Cuba), 1979. Collage Habana; Ana Margarita Ramírez, Caracas, (Venezuela), 1974. Galería Luisa Pita; David Planas, San Antonio De Los Baños, La Habana, (Cuba), 1976. Galería Luisa Pita; Evangelina Esparza, Rosario, (Argentina), 1980. DDR. Art Gallery; Fabio Camarotta, Buenos Aires, (Argentina), 1969. Art Lounge Gallery; Gustavo Díaz Sosa, Sagua La Grande, (Cuba), 1983. Galería BAT Alberto cornejo; Isabel Ruiz, Montevideo, (Uruguay), 1959. Nuno Sacramento Arte Contemporânea; Isabela Puga, Caracas, (Venezuela), 1997. Galería BAT Alberto cornejo; Marlene Stamm, Vacaria, São Paulo, (Brasil), 1961. Trema arte contemporânea; Mono Cieza, Argentina, 1969. Fousion Gallery. Roger Sanguino, Maracay, Venezuela, 1968. DDR. Art Gallery; Roldán Lauzán Eiras, La Habana, (Cuba), 1987. Collage Habana; Willy Ramos, Pueblo Bello, (Colombia), 1954. Galería Espiral; Yasiel Elizagaray, Sancti Spíritus, (Cuba), 1987. Collage Habana.

A fair is, as you know, a window to the art market and a springboard for the thoughts and actions of those dedicated to creation. Art Madrid is. It is window and mirror. It is the regular appointment in which galleries and artists contribute and place their vision and interaction with the production of meanings in the hands of the public. Photography, drawing, painting, and sculpture are the most present manifestations in this edition. Discursively, they would come to answer that much-discussed question of what is art and what is not. But this time, the questioning is directed by the constant search for a polyphonic feeling, which brings together voices as different as they are authentic, around the figure of the artist who moves, who provides and directs the work in the movement. Whether in a temporary or permanent stay, the action of movement and migration as casuistry forever surround the exercise of creation.

As an art fair, we are interested in setting our sights on the production built from Latin America and the Caribbean, which has taken root in some way in our context. With increasing flow, artists such as those mentioned above move to other territories looking for other forms of life, and other experiences, thus articulating scenarios that give meaning to the messages that their works are capable of transmitting. Whether in an obvious way or permeated by some lyrical, poetic veil, raising the flags of denunciation or the activation of suspicion, they recount the impact that the change experience has left on their vision of the world. At this time, as the theoretician Néstor García Canclini would say, post and multi, more or less sophisticated repetition does not transcend. Attention is deserved by those positions that underline the differences and critically assess the uncertainty of postmodernity.

We ask ourselves, then, if the placidity of a landscape, the expansion of painting as a critical exercise, the rebuke of individuality, the struggle to build one's own space, and the polyphony of identity, which are, in this framework, an extension of Latin America and the Caribbean should speak from a single place. We think not. We dream of the possibility of being not only a mirror of current events but also a window of access to questioning. To be, above all, the right place for artists who allow themselves to take risks, venture out, and originate the birth of a fertile change in the land in which they reap their legacy.