INTERVIEW TO MARIO GUTIÉRREZ CRU, THE CURATOR OF THE PROGRAM ART MADRID-PROYECTOR’20

Jan 30, 2020

art madrid

We interviewed Mario Gutiérrez Cru, the curator and director of the video art platform PROYECTOR, who will be in charge of the Art Madrid’20 program of activities. To celebrate our 15th anniversary, we have prepared our most dynamic and daring edition in which to enjoy video art, action art, sound art and performance like never before. Live art will turn this event into an authentic experience, with the accurate and renewed criteria of Mario Gutiérrez Cru.

How did the Video Art Platform PROYECTOR begin and where is it now?

PROYECTOR started in 2008 as an annual video art festival in the disappeared Espacio Menosuno. This independent project linked more than 100 people who supported contemporary art as a crowdfunding, even before that concept became fashionable in Spain. This collaborative model made possible an art centre where showings, experimental concerts, meetings, projections and residences were common, in a moment when installations, performances, sound art and video art were still great strangers.

Since the first edition of PROYECTOR, we have chosen to invite international creators and festivals to make site specific pieces, which allowed us to know the panorama of the video in other countries. This opened doors for the festival to be an annual mapping of the independent spaces of the city. We went from a headquarters to the current configuration with a dozen spaces both independent, public and private. The festival finally became a platform due to its continuous work and now travels to other countries with which it collaborates, shows and shares.

At present, it is a consolidated project that brings together about 100 artworks during 2 weeks of September. Video installation, video performance, hybrid proposals and works of international festivals in an auditorium format, besides the professional meetings with festival directors, museums, curators, lawyers, collectors, curators and artists that are the bulk of our meetings.

How do you think video art and action art are generally perceived by the public in Spain? Do we still have to educate the public in the understanding of these disciplines compared to other countries?

Both video art and action art are still the great unknown by the vast majority of people. Although increasingly, thanks mainly to the efforts of independent festivals and institutions, the public is getting used to these manifestations. These proposals were born in the last century and, little by little, the spectators begin to develop that pleasure that only art can give. But as we all know, the changes, the unknown, produces a jump to the void, a lack of comprehension that requires time and find on our way pieces that we are passionate about, that make us think, that allow us to escape, reflect, wanting to know more. And to all this, if we add the participation of professionals who tell us about their creation, their passions, their way of doing, thinking, their weaknesses, their fears or their failures, we will manage to humanise.

Therefore, both in PROYECTOR, as in my work as a curator and teacher, we make this effort to try to open knowledge to these thrilling proposals. The word to educate is dangerous because who are we to educate, to instil in others our ideas? What we try is to implant seeds of passion for art, either live with actions or performances, as in deferred with moving images, video creations, or even experimental cinema. I don't think Spain is very different from other neighbouring countries. The effort to give visibility, want to show, open these proposals to the public is constant and want to share in each meeting we do or in each festival I attend.

It is the second year that you are as curator of the ART MADRID-PROYECTOR program, how do you think the project has evolved for this edition and how has it affected everything that you have seen throughout this year?

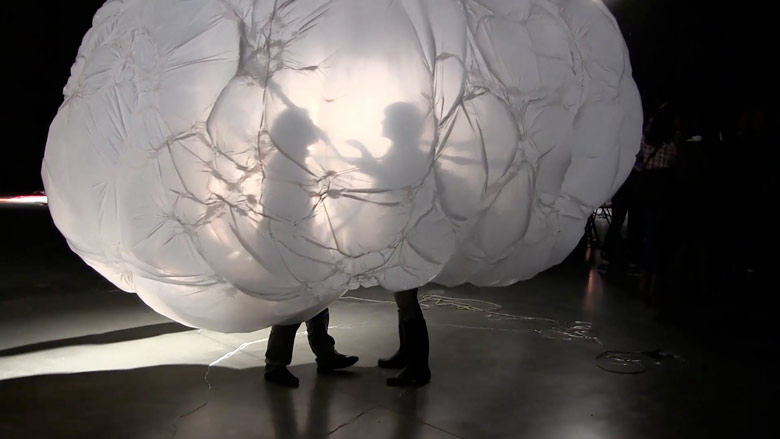

The truth is that it is a surprise and an honour to be a curator again at the fair. Always looking for novelty, surprise, innovation to attract the press and spectators, but renewal is a set of values that require time for the viewer to become familiar with them. And, of course, video art requires a lot of effort to make it habitual. To this we must add the novelties of this year: a commitment to pieces that move between moving images and the “numériques” - as Francophones would say to digital works - pieces with a strong technological presence, either new media , or simply works with motors, mechanisms, inflatables, interactive, auto generative, random... Also, and perhaps the great novelty, is the opening not only to technology but to the use of the body. Artists have been invited to work in the live arts, in that boundary between action art and performance (in its Anglo-Saxon variable) related to the performing arts.

Another novelty of this edition is the creation of a booth within the fair itself where all actions will be developed. In this spot, the meetings with the artists and the screenings of the international curatorship will be presented. I have invited 13 festivals from Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Greece, Morocco, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Argentina. This will give the attendees the opportunity to witness more than a hundred works of maximum relevance on either side of the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

What has been your criteria when selecting the artists and specialists that make up the entire program of activities?

We have trusted in involving viewers of the current creation in video art, new media and action art. This has been divided into four stages. A first one, to present three Spanish artists: Patxi Araújo, Olga Diego y Lois Patiño. Each of these profiles represents a variable of creation: mechanical and digital art in Patxi; the art of flying and creating habitable inflatables in Olga; and the audiovisual creation that moves between the cinema and the lighting video creations in Lois. The three will teach master classes at Medialab Prado, the most important centre of Madrid for these types of proposals.

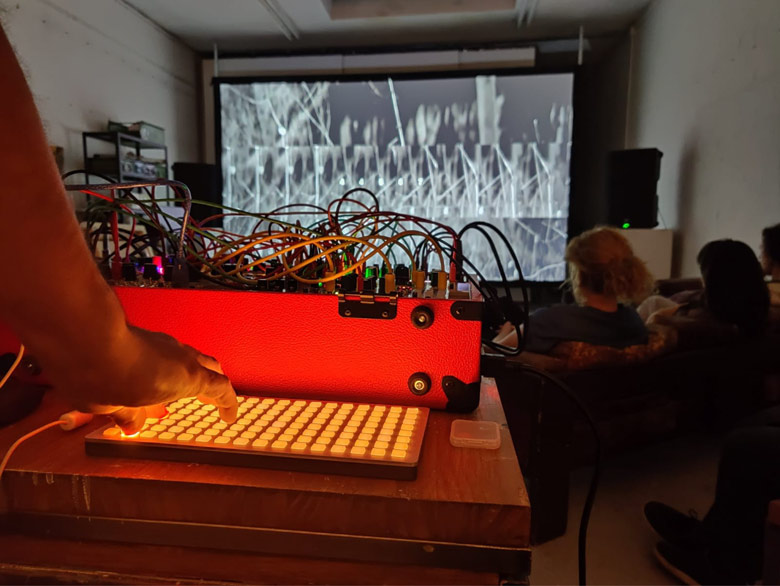

On the other hand, the artist Eduardo Balanza will open his studio, maximum space of creativity and intimacy, to show us his creations of great dimensions, and especially his digital organ with which he has been experimenting for years.

In addition, as every year, we will have in Sala Alcalá 3 a meeting with great professionals who have been behind museums and art centres related to photography, video and new media. Rafael Doctor, Karin Ohlenschläger and Berta Sichel, together with the moderator Miguel Álvarez-Fernández, will give us a good introduction to these types of proposals under the title “From photography to the new media”.

Finally, as I said, we will have a booth at the fair where actions, screenings and presentations will take place. Among the performers are Iván Puñal, Eunice Artur with Bruno Gonçalves, Arturo Moya and Ruth Abellán Alzallú, and Olga Diego, and among the video artists and installation creators: Abelardo Gil-Fournier, Fernando Baena, Mario Santamaría y Maia Navas. Each one of them can represent very different ways of understanding performance, although they all have in common that they use technology (computers, processors, cameras and sensors) to develop them. These creators will tell us about their career of several decades creating pieces in front of the public with a marked claiming nature, or they will invite us to participate, interact live with their proposals adapted or created for the fair itself.

With this, I have tried to create a minimum conceptual and procedural framework that serves as an aperitif for the everybody and that allows mind-opening for spectators and creators.

What do you think of the presence of video art and action art at fairs?

The video art entered with great discretion in the fairs almost two decades ago. The necessary elements to show it with the quality that this art required were still expensive, and potential buyers were scarce, afraid to get out of what their advisors recommend and the possible problems of conservation, care and even the possibility of showing it in their homes.

Action art may have been visible for more time at fairs, although much more at festivals, biennials and Documentas. Perhaps in these latter ones, not considering it as a product to be sold, it allowed much more freedom for both creators and programmers. Documentation, both in photography, as in video or cinema, was very much common especially since the 70's. Large museums and private collectors acquired "memories" of actions they attended or would have liked to. Photography, today is more standardised at fairs and among buyers, but until recently it was also that unknown, that sales challenge. The same goes for the video and that is why the precaution for these acquisitions continues.

Is video art collecting possible? How can this format be transmitted to those who are more sceptical about its artistic value?

Collectors have been buying this type of works for more than five decades and these transactions are increasingly regulated. Lawyers, collectors, festivals and fairs have worked side by side with the artists so that both parties are protected in bilateral relations that respect copyright, acquisition and property rights. In addition, a change in the patronage law is ongoing so that it resembles other’s countries regulations where the acquisition of works of art has great tax advantages that favour the art market and all those involved.

I do not think that people are sceptical about the artistic value, but about their possible future profitability, their loss of value due to their lack of privacy when being present on online platforms or that the same piece could be seen in several galleries or fairs simultaneously. Artworks have a value in themselves, for being made by an artist or conceived as such by specialists, or simply for their decontextualization and placement within the framework of a specialised space, whether an art room, museum, fair or gallery. The value should never be economic, it should be personal: how much I am willing to sacrifice for owning this work, be it time, money or relationships.

What are the essential elements when creating a video art piece? How is the creative process of an artist in this discipline?

Perhaps the only indispensable element to create a video art piece is that it has images that move -many purists wouldn’t believe what I am saying! There are many people who only consider this discipline if it is a recorded image that can be reproduced, or even if a magnetic tape was used to record it. But digital technology has helped to reduce and simplify many of these processes with qualities far superior to all of its predecessor analogue equipment. This allowed a whole generation of creators linked to both film and video to appear, so there were always leaps from one discipline to another. There are also those, like me, who defend that both disciplines are very similar and that for more than a century there were already pieces of video art, even before the word video had appeared.

On the other hand, if we ignore the format in which they have been recorded, perhaps what normally defines video art is its formal, narrative and expressive freedom. They are usually short pieces, they may have experimentation in their way of recording, in their rhythm, colours or sounds that are not common in cinema, and sometimes they use several screens to tell a story, which makes the viewer build in its head the work he/she is watching.

Every artist has a very different process of creation, but perhaps in the first years of video art and almost until this last decade the creator was the also the screenwriter, cameraman, soundman, editor, producer and even seller or distributor of his/her pieces. At present, and especially since The Cremaster Cycle of Matthew Barney was introduced in this sector the creations, back in 2000, the works have become increasingly sophisticated and now it is a great team with great productions that manage to absorb the interest of museums and fairs, which forces artists to need more and more resources to be able to afford large productions that are more common in the film sector, which has significantly increased the price of video art.

There is a large number of languages and techniques that make up the creation of video art. Do you think that, given the technological development, new artistic languages will be generated that we still don't know?

Technology revolutionises languages again and again, as well as what the viewer expects to see. Some of the creators passionate about these advances want to introduce them in their creations and update this discipline. They vary sometimes to such an extent that they can no longer even be called video art and a new word has to appear to replace it, as was the concept of new media in the '90s or, later, virtual or augmented reality.